Hunting for Northern Lights: Aurora Borealis in Art

With mesmerizing colors dancing in the night sky, witnessing an aurora must feel like being inside of a painting. What are the northern lights and...

Marta Wiktoria Bryll 20 January 2025

Fernando Botero’s artworks are probably among the most recognizable in art history. It is enough to look once at one of his plump, “voluminous” characters and objects to recognize in any other work the style of this Colombian figurative artist. So if you like his creations and have the chance to travel to Colombia, there are two places you absolutely have to visit: the Botero Museum in the capital, Bogotá, and the Museo de Antioquia in his hometown, Medellin. Here is a review of some of Botero’s artworks you can find there.

The “most Colombian of Colombian artists” had spent most of his life living and working abroad, so there is little chance of you meeting him on your Colombian travels. But these two museums house an impressive number of Botero’s works – and with them, a big chunk of his life, his passions, and the history of Colombia.

Located in La Candelaria, the trendy and touristy neighborhood of Bogotá, the Botero Museum is said to house one of Latin America’s most important international art collections. It consists of 208 art pieces: paintings, drawings, and a room full of sculptures.

No less than 123 pieces of the collection are signed by Botero; the remaining 85 are from famous international artists such as Marc Chagall, Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, Sonia Delaunay, and Claude Monet. That is not the only reason why the museum is named after Botero though; all of these artworks belonged to the Colombian master and were donated by him in the year 2000 to the city of Bogotà. The mayor of the capital at the time agreed to build a museum to showcase the donation, an exhibition that was curated by Fernando Botero himself, with one condition: no piece should be moved, sold, or lent once it had found its place in the building.

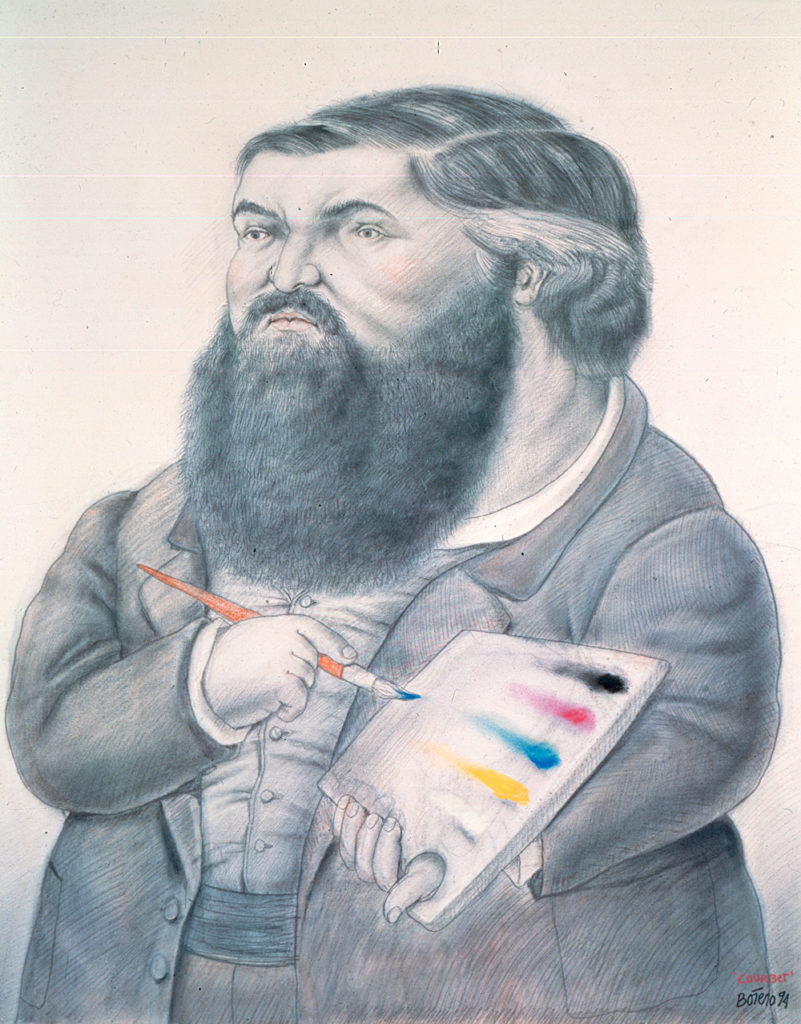

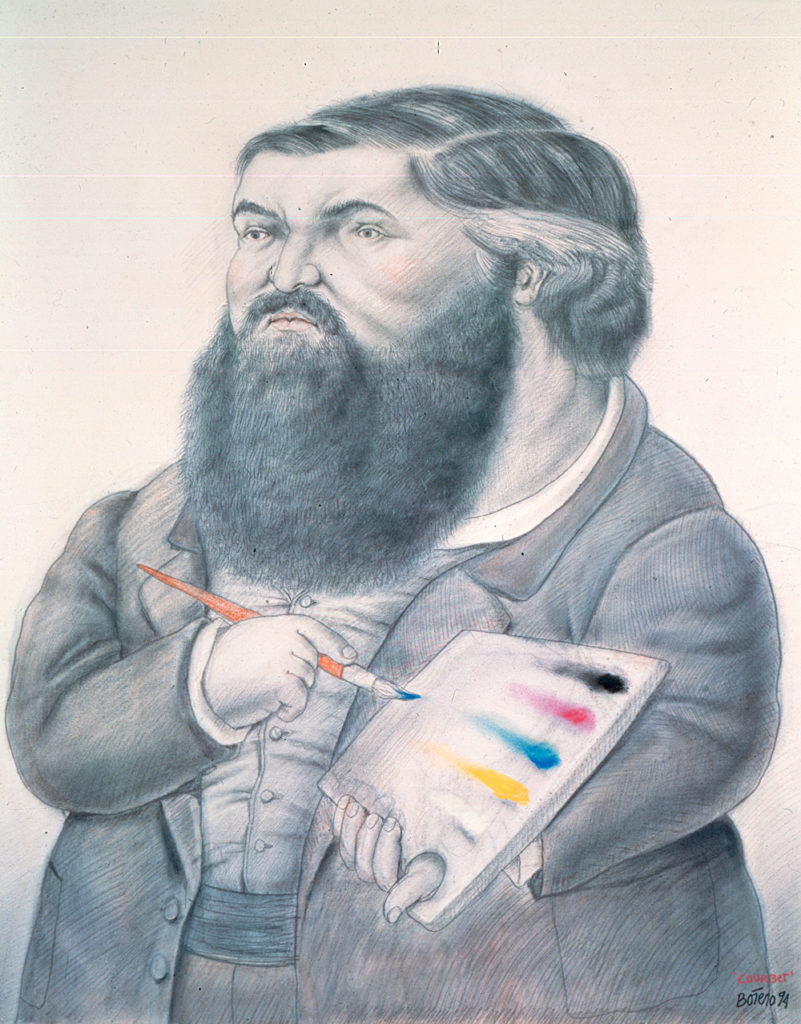

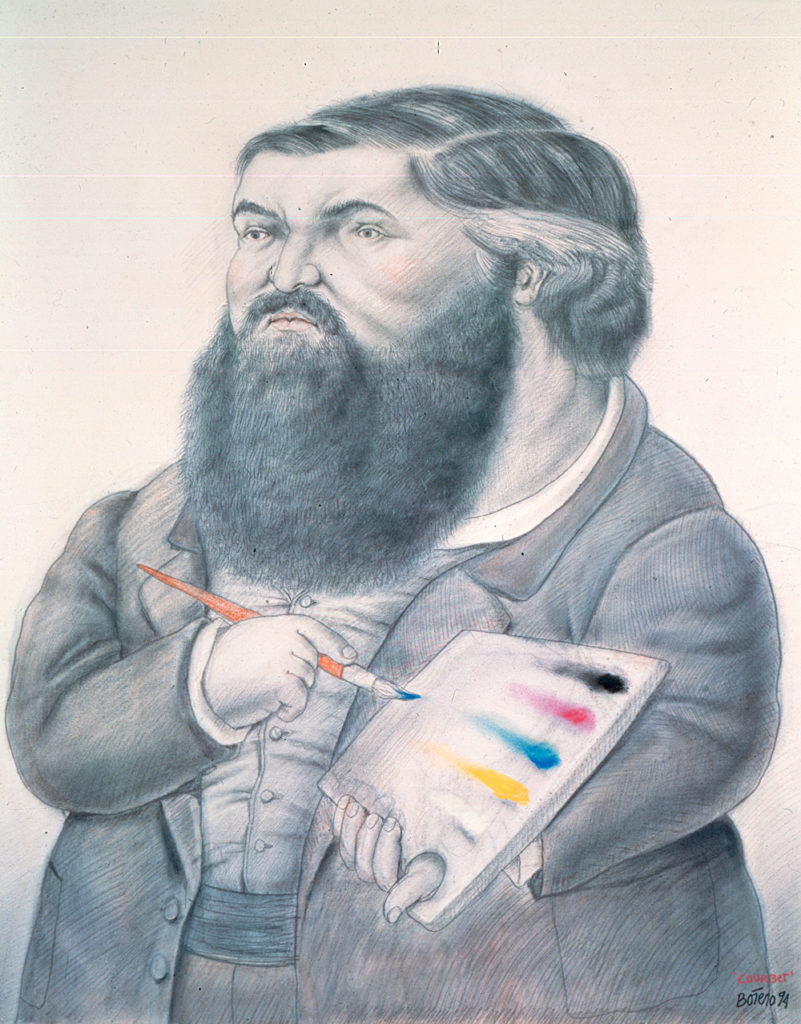

Botero was famous for his remakes of classic masterpieces. A bit like with a naive imitation by a talented kid, it’s hard to tell whether these remakes are praise or criticism, tributes, or caricatures. They certainly border on the irreverent! But considering Botero’s love for, and inspiration from, the Spanish masters Diego Velazquez and Francisco Goya, we understand that this is not meant as a ridiculing parody.

Here, cheeky Fernando took on one of the most famous paintings of all time, the enigmatic Mona Lisa (aka La Gioconda), usually encased in tight glass in her Parisian refuge. The structure is there, the position is there, the clothing and even the famous mysterious smile likewise. In other words, everything looks like a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting with a fish-eye effect. Insolent parody or accolade? Piece of art or naive drawing? The good thing about art is that you can decide for yourself!

Among the many works he donated to the museum, there is a large collection of French Impressionists. If his sympathy for them was not clear enough, here is the final proof. I do not think one single minute that these chubby, friendly-looking characters can be anything but a tribute to these masters!

Botero was clearly a citizen of the world, changing residence every so often. His first stay in Paris was in 1953, and he spent most of his time in the Louvre. This is probably where he first discovered first-hand the works of the Impressionists.

These pieces with pencil and watercolor show the skills of the artists on paper, retaining the Boterismo style that is so recognizable.

Fernando Botero, after finishing one of his painting series, declared:

After all this, I always return to the simplest things: still lifes.

Fernando Botero, quoted in Dorotheum.

And whether they are fruits, cakes, bottles, or musical instruments, still lifes are indeed a recurrent topic on the walls of both museums!

I chose this particular one as a good example of the importance of colors in Botero’s paintings. A critic once talked of “the sharp use of color that gives his works a seductive beauty and an elemental impact”; he added that the colors were a way to convey pathos and emotions.

Orange Oranges on an Orange Wall could be the title of the painting. Here, the color underlines the rotund shape to emphasize the juicy flesh of the fruit; the flesh seems bright under the light and sticks out of the painting. With the undersized cutlery adding to their enormity, wouldn’t you want the fresh juice of these Colombian oranges?

This magnificent hand greets visitors in the entrance hall, like a stout bronze “hello” from the museum building. Despite the usual plumpness, there is a definite grace and subtlety in the shape and the position. It resembles the hand of a chubby baby sticking out of the cradle, looking for his mother’s finger. This is a perfect example of how the artist manages to create a “fat” sculpture that does not feel ponderous. Having said that, it’s better not to look at it from behind, so as not to get another meaning from the fingers.

The museum contains one room full of sculptures by Botero; read on to see more of those on Botero Square.

The hand in the Botero Museum is part of a series of only left hands from the same cast, scattered throughout the world: Bogota, Medellin, Madrid… And where else? If you find one of Botero’s left hands somewhere, let us know in the comments section!

Museum of Antioquia is much bigger. It showcases several temporary and permanent exhibitions, including colonial and religious art, pieces by modern and contemporary international artists, and many Colombian artists. It contains works by other nationally acclaimed artists such as Antonio Caro, Francisco Antonio Cano Cardona, and other natives of the region, namely Eladio Vélez and Pedro Nel Gómez (who contributed in particular no less than 11 impressive murals).

The complete collection of Botero artworks that are shown in the museum was donated by the artist himself at different times. They are divided into two rooms, a third one showcasing works by international artists that were also donated by Fernando Botero.

Despite his regular fallback on still lifes, Botero mainly focused on situational portraiture. Life in Colombia’s towns and countryside, people dancing or at the bar (or dancing at the bar), in their bathrooms, at the beach, etc. are scenes that have always been very present throughout his career.

Here, the artist depicted his first son, Pedro, affectionately called Pedrito, dressed in a uniform and playing in a room. The trademark plumpness is there – in Pedro, in the horse he’s riding, in his toys – but nothing looks ridiculous or deformed. Instead, an aura of benevolence and family love radiates.

This piece was painted in 1974, only a few months after Pedrito died in a car accident, at the age of four. The Museum of Antioquia subsequently inaugurated the Pedrito Botero room, showcasing several works from his daddy, with a pedagogical approach to art for the younger audience.

There’s no doubt about it: Catholicism is very important in Colombia. Most public buses, taxis, and street food stalls bear one or several images of Christ or the Virgin. Sentences are written on the windshield, for example, “This morning I left with God. If I don’t come back, it means I went with him” (true story).

With that in mind, I wonder how Colombians react when they see this painting. Despite the usual Boterist chubbiness though, this portrait follows the century-old canons in the religious iconography of Christ; the stigmas, the dark background, the lack of perspective, and the blood so dear to the counter-reform movement (literally). Jesus doesn’t seem dead but simply closing his eyes. The general atmosphere is peaceful, showing yet again how Botero’s style can be deep and moving.

When young Botero was only 12 years old, his uncle (who was substituting his dad who died a few years before) sent him to a school for two years to become a matador. During that time, he started drawing and using watercolor, which quickly replaced bullfighting in his life.

Still, that period of his childhood has remained an important source of inspiration for the artist, who has realized a great many drawings and paintings on the subject. This one is part of a large exhibition, representing at times the man, at times the bull, and other times the two together in some nasty interaction.

Despite the movement and the dynamism in this piece, I find that the bull looks too peaceful, almost as if he was about to lick the matador’s face like a happy dog. From his paintings only, it’s hard to guess what Botero thought of bullfighting; did he like it or consider it a savage business? What do you think?

It is impossible to mention Colombia, and even more so, the city of Medellin, without mentioning the drug cartels. Their activity has left dramatic traces in some neighborhoods and in the memories of many of their inhabitants. Nowadays, the face of the richest and most violent drug lord, Pablo Escobar, can still be seen on t-shirts sold in the tourist quarter to foreigners who think that’s cool. That is not cool – that’s violence, blood, and tears.

Anyway, in 1993, Escobar was eventually shot down by the police on a rooftop in Medellin. When that occurred, Botero, who was only 10 years his elder, was already living abroad. The event was of the utmost importance for the country, for Medellin, and probably for the artist as well. He painted several pieces about it, including The Death of Pablo Escobar and Pablo Escobar Dead.

The fat characters of Botero can make the viewer smile but the political meaning here is not funny at all. The monstrous size of the gangster against the roofs shows just how significant he was for Medellin; the rain of bullets symbolizes the means that were necessary to his demise. In other works, the exaggerated proportions can represent the characters’ inflated egos and sense of self-importance.

Right outside the Museum of Antioquia, 23 sculptures created and donated by Botero adorn a wide square vibrant with movement. It is a touristy area, but also with a lot of local life. There, you can find street sellers, old men sitting on the benches, young girls people-watching, business people from the nearby offices, pickpockets, etc.

The 23 large sculptures don’t feel cramped in that large area. They’re ideally scattered along the alleyways, under the trees, and around the beautiful Palacio de la Cultura. They represent various topics favored by Botero, for instance, animals, people, and bodies. Tourists take selfies to bring them back home while children play on them.

I want to share a story related to a Botero sculpture; it took place only a 10-minute walk away from the Museum of Antioquia. In the 1990s, Medellin was one of the most violent cities in the world. Ridden by powerful drug cartels, guerrillas, and corrupt politicians, the city was the regular scene of shootings and bombings.

In June 1995, a bomb exploded on San Antonio Square, killing 29 people and destroying the nearby sculpture, a work of Botero representing a bird. The terrorists stated subsequently that the attack was against the politics of Fernando Botero Zea, son of the artist and Minister of Defense at that time.

Botero insisted that the pieces of the broken statue shall not be removed, as a “memorial to the imbecility and criminality in Colombia”. He started working straight away on a replica and donated this new bird to the city in 2000. Now, it stands next to its damaged brother. They’ve become part of the urban landscape of Medellin: the Wounded Bird and the Bird of Peace.

Fernando Botero was an unabated artist until his death in September 2023 – and a generous one! His donations compose the collections of two important museums and adorn several squares in Colombia.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!