It was only three years ago, after a long civil war, that Beirut’s art scene began to find its feet. Despite ever-present political corruption, an unsteady economy, and rising inflation, the Mediterranean city has recently become a hot-spot for Arab artists that often attracts an international clientele. However, an egregious oversight by the city’s authorities would bring it to a crashing halt on August 4, and a fire would do it again on September 10, 2020.

Before the Blast

About five years ago, Beirut’s art scene came alive when many private galleries, museums, and foundations opened their doors. In September of 2017, Beirut was buzzing with activity stemming from the city’s art week which was scheduled at the same time as the Beirut Art Fair. Various gallery openings occurred throughout the city while the Sursock Museum hosted a crowd for a book launch by renowned artist, Marwan Rechmaoui. The previous year, art fair attendees reportedly spent about $6 million on works which were mainly paintings. Due to its substantial profits and increasing popularity, many people credit the Beirut Art Fair with propelling the popularity of Lebanese art around the world.

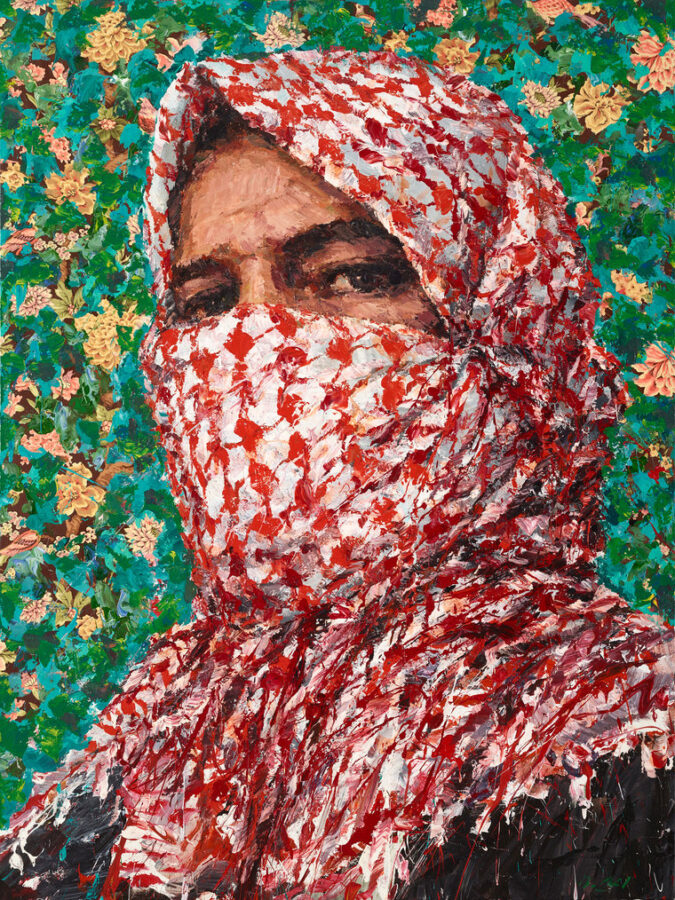

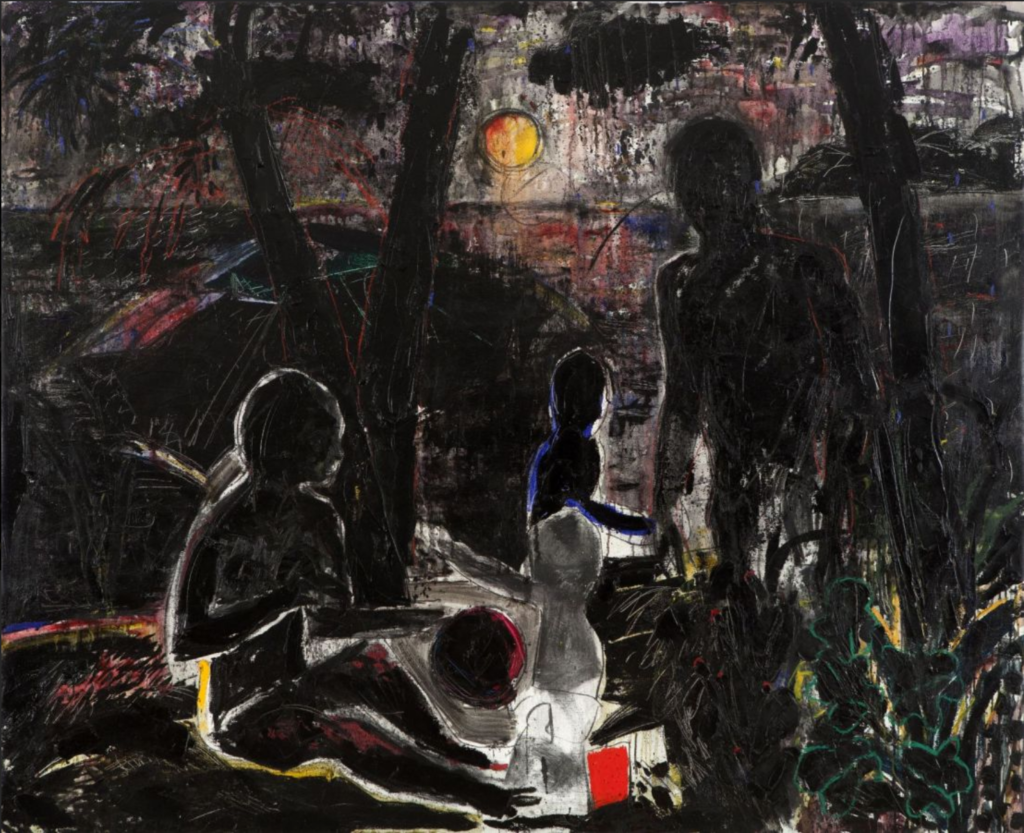

For quite some time, the Lebanese seaside city has drawn on its artistic community to enrich and showcase its cultural fabric. Consequently, the art produced by Beirut’s ever-growing artistic population reflects on the city they call home. In an age where stereotyping Arabs as terrorists or thugs is the norm, Basel Dalloul, founder of the Dalloul Art Foundation, believes it is imperative to showcase the talent, creativity, and culture found in the Mediterranean.

Only a few years ago, Dalloul began plans to open a museum to house the 4,000-piece Modern and Contemporary Arab art collection compiled by his parents, Dr. Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul. Over the past 45 years, the collection grew into a trove of artistic treasures created by Lebanese masters such as Paul Guiragossian and Etel Adnan, Egyptian modernists Mahmoud Said, Effat Naghi, Ezekiel Baroukh, as well as Iraqi greats Dia Al Azzawi and Jewad Selim. The collection also houses work by emerging contemporary artists, such as eL Seed and Mounir Fatmi.

Much like collectors in other places, Dalloul’s parents valued art as part of their country’s vibrant visual culture, and more importantly, documentation of its turbulent history. Basel Dalloul said the following regarding his parents’ views on the subject:

“Artists are the truthsayers of the world. Throughout history, they depict what they see — it’s not a history that’s been rewritten or sweetened. In our part of the world, at least, it’s the brutal, ugly truth sometimes. My parents (bought) quite a few paintings of politically charged art.”

– Basel Dalloul, Arab News.

Beirut’s Cultural Crown Jewel

Atop a hill in a swanky Beirut neighborhood lies what many consider the main attraction of the city’s art scene: The Sursock Museum. Known as much for its blend of Ottoman and Venetian architecture, as its art collection, the museum has long been a cultural hub in Beirut.

Upon his death in 1952, Lebanese art collector and the museum’s namesake, Nicolas Sursock, left his mansion to Beirut’s citizens. Realizing Lebanon’s need for institutional support of the arts, he wrote in his will that the halls should become an art museum. Sursock wished “for this country to receive a substantial contribution of fine art works, and that my fellow citizens might appreciate art and develop an artistic instinct.”

After briefly serving as a residence for visiting officials, the museum opened its doors in the 1960’s. Throughout the decade, the mansion’s salons were filled with poets, playwrights, and other artists who likely exchanged ideas. The museum soon began showcasing art in a similar mode to the French Salon. Famous Lebanese artists, such as Shafic Abboud, Elie Kanaan, and Adel Saghir were among a few whose work was shown at the annual Salon d’Automne. Additionally, the museum organized an array of rotating exhibitions, highlighting work from all around the world.

From that point forward, despite a long civil war and its’ subsequent uncertainties, the Sursock never closed. The museum remained at the heart of Beirut’s art scene as a site for concerts and art exhibitions, while remaining a hub for the dispersion of modern and contemporary art. However, in 2008, the museum closed for a $15 million renovation aimed at transforming the mansion into a 21st century cultural institution. After reopening in 2015, the museum regained its position atop Lebanese culture, remaining a museum as well as a popular backdrop for photoshoots.

An Unforeseen Disaster Strikes

During the fall of 2019, Beirut endured weeks of protests demanding political change that became locally known as the October Revolution. On top of that, the country’s economy was crumbling amid rampant inflation, shutdowns, and financial losses brought on by the pandemic. To make matters worse, the city’s inhabitants had been limited to one or two hours of power a day. As if to bring on the adage, “when it rains, it pours” to life, an even more devastating an ill-timed disaster stuck.

For six years, an arsenal of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate sat unnoticed and unregulated in a warehouse in Beirut’s port. That is, until August 4, 2020. Around 6 p.m., an explosion unlike any war-time bombing or airstrike shook the city to its core. Residents felt the floors shaking but had no idea what was going on. The blast, caused by the detonation of the ammonium nitrate, propelled shock waves through the city, blowing in nearly every window in its path and wreaking havoc on nearby structures. At least 200 people were killed in the explosion, 5,000 were injured, and at least 300,000 residents are now homeless.

-

Photograph of damages in Marfa Gallery due to the August 4 explosion. Image courtesy of Marfa Gallery. -

A picture shows destruction inside the Saint George Maronite on August 5, 2020 in the aftermath of a massive explosion in the Lebanese capital Beirut. Photo by JOSEPH EID / AFP via Getty Images. -

Damages inside Sfeir-Semler Gallery. Image courtesy of Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Unfortunately, many institutions that make up Beirut’s art scene lie in the Gemmayzeh district near the port and thus, were in the immediate vicinity of the blast. The Marfa Gallery is one. Established only five years ago, the gallery was destroyed in a matter of minutes. Its windows were shattered and its interiors diminished to rubble. A collection of paintings by Beirut-based artist, Tamara Al-Samerraei, was on view at the time. Now, it has also been completely lost.

The evening before the blast, Galerie Tanit, also located in the port district, hosted a private opening for Lebanese artist, Abed Al Kadiri’s newest exhibition, Remains of the Last Red Rose. However, the gallery was destroyed and along with it, much of Al Kadiri’s work.

According to an official study conducted by the Directorate General of Antiquities of Lebanon in conjunction with UNESCO and the International Council of Museums, about 650 cultural heritage sites were damaged. Beirut’s Opera Gallery was also completely destroyed. Several other institutions, including the Sfeir-Semler Gallery, the Saint George Maronite Cathedral, the Arab Image Foundation, the Beirut Art Center, the National Museum, and Ashkal Alwan were also impacted by the blast. The Sursock Musuem was heavily damaged; its stained glass windows were completely shattered, while the interior and several of its paintings have been badly damaged. Thankfully, the exterior structure remains intact. Zeina Arida, director of the Sursock Museum, told The Art Newspaper:

“This is the strongest explosion I have ever witnessed. The museum is devastated. A lot of damage has been done to the structure of the building at a time when the dollar in Lebanon is so high that I don’t know how we will afford to buy new glass for the skylights, the windows, and the exit doors. We don’t have the means to buy new materials. It’s horrible to see five years of work in utter destruction—even during the civil war it wasn’t this bad.”

– Zeina Arida, The Art Newspaper.

The Rocky Road to Recovery

While Lebanon’s history has been marred by periods of violence and destruction, it has always been rebuilt. As gallery owners sort through the rubble and debris, they are left wondering how, or if, they will reopen. Some have decided to stay, hanging banners on storefronts declaring their tenacity. However, many residents, including its creatives, have decided to leave. Local carpet maker, Mohamed Maktabi, said,

“Our resilience is a curse. I’ve been rebuilding all my life and I don’t want to do it again! But the truth is that we will rebuild. We are here to stay. But we are rebuilding knowing that it will likely be destroyed again.”

– Mohamed Maktabi, Artnet.

On August 11, about 30 cultural institutions, including the Louvre, the Global Heritage Fund, UNESCO, ICOM, and the World Monuments fund signed a statement of solidarity, pledging all the cultural first aid and long-term assistance available to help Lebanon recover the large portions of its heritage damaged in the catastrophe. The package, funded by the Geneva-based International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas, will distribute $5 million in aid.

Among the top priorities of this initial aid package are restoring the National Museum, which contains many archeological artifacts. In addition, portions of the funds will be given to libraries and other museums throughout the city. The funds will be managed by the Prince Claus Fund and the Lebanese Committee of the Blue Shield.

Despite the outpouring of international aid, the Lebanese government seems to offer little help to inhabitants eager to rebuild. In the ten days immediately following the explosion, Lebanon’s government resigned due to escalating anger over the negligence and corruption that led to the blast. Seeing as the country’s ruling party has other priorities, many Lebanese citizens fear for their country’s future.

Protests have once again erupted and turned violent as the military uses force to try to subdue protestors. Journalists, artists, activists, and citizens perceived to be against the regime have been detained and interrogated by the military. Lebanese banks have placed limits on the amounts of Lebanese pounds available. Right now, that limit sits at about $200 per week but many fear that could soon take a turn for the worst. Zeina Arida, director of the Sursock Museum estimates it will take millions of dollars to repair the museum but is uncertain where the funds will come from.

“The banks have confiscated our funds,” she said. “I don’t how we’re going to do it. It will take years to restore the museum.”

– Zeina Arida, Hyperallergic.

How You Can Help

Owner and founder of the Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Andree Sfeir-Semler, says for now their focus is to help the cultural sector as best they can. At this time, that entails supporting independent fundraising efforts that will help artists who have been injured, lost their homes, friends, or their studios. In a catastrophic situation such as this, no donation is too small. If you are able, please consider making a donation to one of the funds listed below so Beirut’s art scene can return to its glory.

Read about Lebanese artists: