Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

When we talk about Impressionism, usually the names of Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Degas come to mind. However, let’s not forget about another important figure of this movement—Berthe Morisot. She was one of ‘the great ladies of Impressionism,’ a student of Camille Corot, wife of Eugène Manet, brother of Édouard Manet. Despite her significance, Berthe Morisot has often been overshadowed by her more famous contemporaries.

To understand Morisot’s work and the challenges she faced as a woman artist, it’s important to analyze Berthe Morisot’s paintings in the context of her time. This article will explore her journey through five works.

She crushes on her palette the petals of flowers, to spread them haphazardly on her canvas in witty brushstrokes, full of the breath of life . . . they end up producing something delicate, lively and charming, which one guesses at more than one sees it.

Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes, 2010.

Berthe Morisot, The Mother and Sister of the Artist (The Reading), 1869–1870, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

It can be said that Berthe Morisot was fortunate to be born into a well-off family, as her parents encouraged her and her sister, Edma, to take painting classes. However, being a woman in the latter half of the 19th century meant that she faced certain limitations and challenges.

Morisot was acquainted with Édouard Manet, whom some critics considered her to be a pupil of; however, this was actually not the case. Manet painted portraits of Morisot and influenced her work in various ways. For instance, rather than verbally expressing his thoughts on Berthe Morisot’s paintings, he retouched The Mother and Sister of the Artist. This may indicate his condescending attitude towards Morisot as a female artist. Morisot knew she was the equal of anyone else and secretly suffered from being treated as an amateur.

Berthe Morisot, The Cradle, 1872, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

One of the major challenges faced by women artists at that time was the difficult decision that female painters had to make about whether to pursue a professional career or get married. Berthe Morisot, however, managed to balance both roles and became a successful painter, wife, and mother, while her sister Edma gave up painting after getting married.

Morisot addressed the topic of motherhood in The Cradle. In the painting, the mother is bent over her child, looking thoughtful and meditative. The portrait depicts Edma, the artist’s sister. There are echoes of Dürer’s Melancholy in this work, as well. The Cradle was presented at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. A critic commented on the exhibition in a rude manner, saying: “Five or six lunatics—among them a woman—a group of unfortunate creatures.”

Berthe Morisot, The Psyche Mirror, 1876, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain.

Berthe Morisot’s paintings depict women who are thoughtful and immersed in their own world, their rituals, and their families. Could Morisot have depicted noisy companies in cafes or men? Unfortunately, the era dictated social conditions that only men could freely attend public places and take sketches. Additionally, due to social conventions, it was not appropriate for women to be alone in a studio with a man unless he was a close family member.

In this painting, Morisot depicts a girl in front of a mirror. From Morisot’s point of view, she is not flirting or seducing, as a male artist might have portrayed. She is not concerned with the viewer at all; she is busy with her toilet, and it is as if we are spying on her without her knowledge. Morisot creates an amazing effect in this work: we do not appreciate the beauty of what is depicted, but rather we want to understand their state of mind and comprehend what their thoughts might be, perhaps even to become like them. Rather than simply looking at these women, we imagine what it would be like to be in their position.

Berthe Morisot, Eugène Manet and His Daughter at Bougival, 1881, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France.

If Impressionism was fighting a battle with academism, then Berthe Morisot was a revolutionary within the revolutionary movement. As we have already mentioned, she combined her career as an artist with marriage and motherhood. Therefore, the members of her family—her husband and daughter—became the subjects of her paintings. It is also worth noting that after marrying Eduard Manet’s brother, Eugène, Berthe Morisot did not change her surname, which emphasized her social position as a woman in her class who had to fight against prejudice.

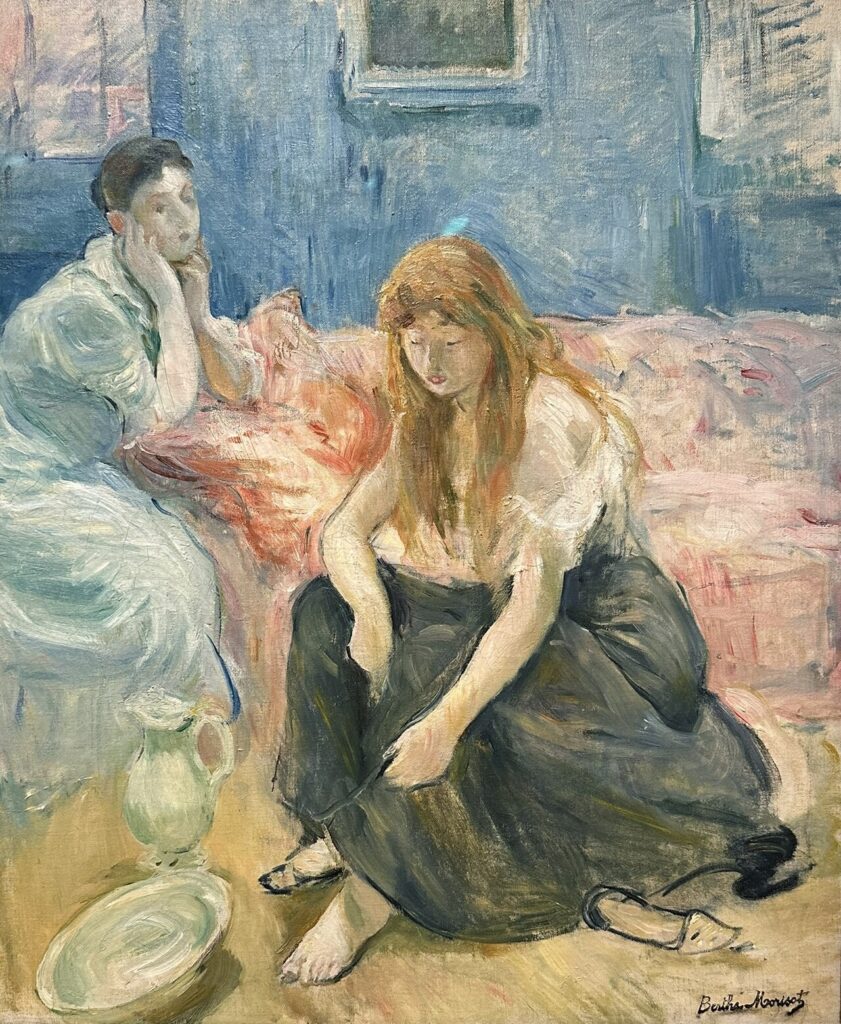

Berthe Morisot, Two Girls, 1894, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, USA.

The Two Girls, created at the end of Berthe Morisot’s career, like many of her paintings, captures young women seated at home, immersed in daily routine. The figures stand out with volume and are outlined with bold brushstrokes that set them apart from their surroundings. This approach, as well as her increasing use of preparatory sketches for her paintings, was influenced by Auguste Renoir, who was a close friend of hers during the last decade of her life.

I do not think any man would ever treat a woman as his equal, and it is all I ask because I know my worth.

Kathryn Hughes, “Berthe Morisot: The Forgotten Impressionist,” The Telegraph, December 13, 2010.

Art historians of the Impressionist movement had been critical of her work, so she was quickly dismissed as a minor artist, more due to prejudices against her gender than the quality of her art or her position within the movement. Luckily, however, now the fair attitude and interest in her creative achievements are increasing.

“Review of Berthe Morisot by Jean-Dominique Rey, Sylvie Patry, Sylvie Patry, Cindy Kang, Marianne Mathieu, Nicole R. Myers, Bill Scott; and Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist by Patry Sylvie, Kang Cindy, Mathieu Marianne, Myers Nicole R., Scott Bill,” Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2 (FALL / WINTER 2019), pp. 40–45 (6 pages), Published By: Old City Publishing, Inc.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!