Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

29 December 2024 min Read

The Birth of Venus is probably the most famous painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and it is considered a masterpiece of French Academic art.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

The art world of 19th-century France was dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which instructed art students, sponsored annual exhibitions and promoted traditional subjects. The Academy sanctioned polished illusionism to express historical scenes, mythological stories, and dramatic moments. William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) was one of the leading artists of the Academy during the late 19th century. He enjoyed state patronage and public popularity through his flirtatiously graceful and refined paintings. The Birth of Venus is probably his most famous image and is considered a masterpiece of French Academic art.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Self-Portrait, 1879, Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Canada.

Bouguereau’s Birth of Venus is an oil on canvas with a portrait orientation, measuring 300 cm high and 215 cm wide (118 in by 85 in). Interestingly, its aspect ratio of almost 2:3 prevails among 21st-century images after the prevalence of smartphones. Therefore, while the painting is from the 19th century, it can easily fit on modern display screens.

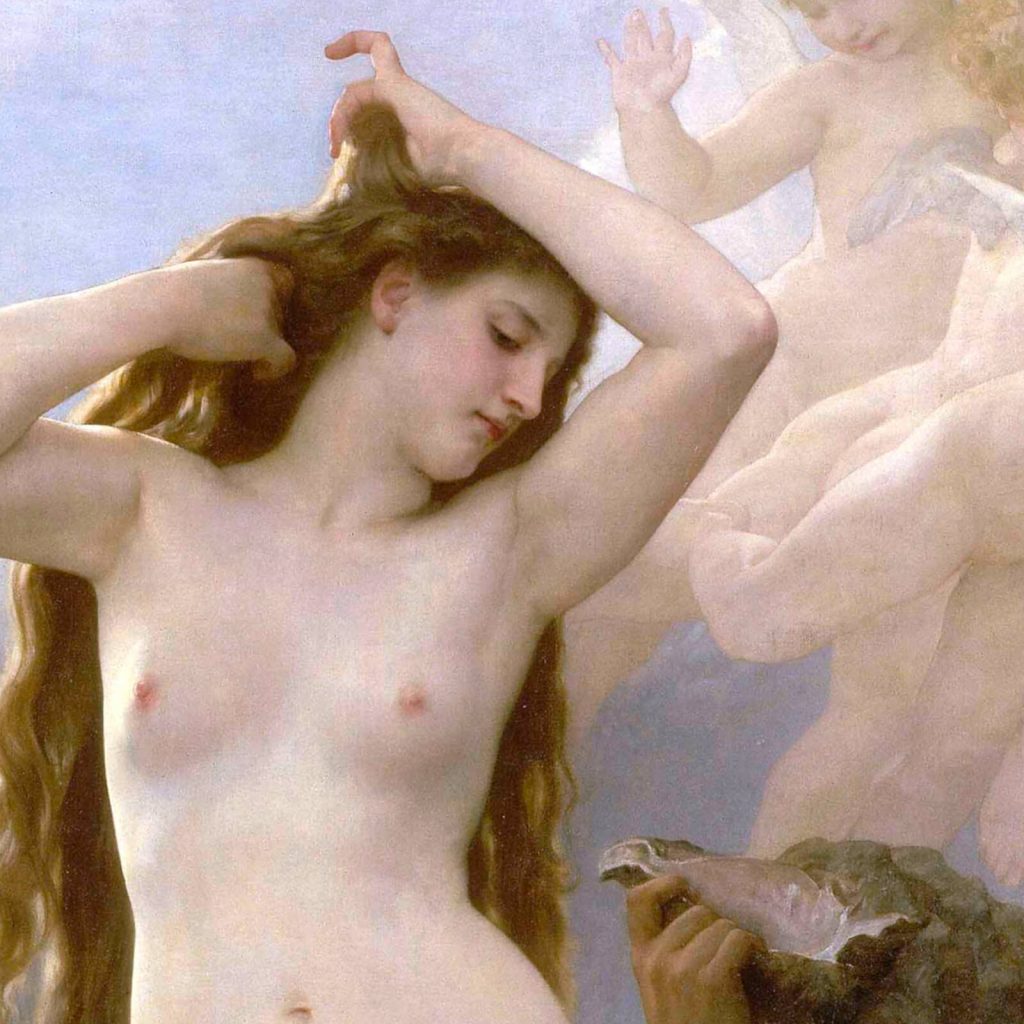

The painting presents a beautifully nude Venus standing on a large scallop shell. She is the epitome of the ideal Greco-Roman female form through her hairless pubic mound, her small breasts, wide hips, long flowing hair, and smooth, unblemished skin. She stands in contrapposto with her left leg engaged, bearing her weight, and her right leg bent at the knee. Her upper body sways in counterbalance and forms an S-curve common in the Greco-Roman period, later revived in the 14th century and popularized as the Gothic S-curve onwards. Unlike the more famous Birth of Venus (ca. 1485) by Sandro Botticelli, Bouguereau’s Venus does not try to cover her pubic mound and breasts with her hair. Some 19th-century viewers said her pose was immodest and boldly exhibitionist. Yet if the Roman goddess of erotic love and feminine beauty cannot embrace her natural sexuality and bodily charm, then who can?

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Venus is one of the twelve Olympian gods. She is the Roman equivalent of the Greek Aphrodite of erotic love and feminine beauty. She has been a subject favored by artists over the past two millennia by being respectable and as a convenient excuse to create a seductive female nude. Even today, in the 21st century, female nudity and sexualization are still considered taboo and even crimes in many countries. Under such contexts, Bouguereau explored an erotically charged subject within the thinly veiled guise of respectability. He did not paint a naked mortal woman; he painted a nude immortal goddess. The viewer should thank the French Academia for elevating a heterosexual male’s gaze from a peep show to art.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

The myth of the birth of Venus is strange; it is not like conventional childbirth. The story began with the primordial deities. The Roman god of the sky, Caelus (Greek Uranus/Ouranos), was in dispute with his family, primarily his son Saturn (Greek Cronus), the Roman god of time, wealth, and agriculture. As an ultimate act of rebellion, Saturn severed Caelus’s genitals with a sickle and threw them into the ocean. The penis and scrotum released sperm, then created a frothy sea foam. This foam (aphros in Greek, hence Aphrodite) brought Venus/Aphrodite into being upon a scallop shell. Venus then drifted ashore onto the Aegean island of Cythera with the shell. These final moments before arriving at shore were captured by Bouguereau.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Surrounding Venus are various figures announcing her birth and arrival. At her feet on the painting’s right are her son, Cupid, with his love interest, Psyche. Cupid’s presence is anachronistic: How could Venus’s son be born before Venus? Including him seems to expand the painting’s mythological imagery at the expense of chronological accuracy.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Cupid and Psyche straddle a dark dolphin which became a symbol of Venus. Accompanying Cupid and Psyche are a shower of putti or cherubs. 13 in total fill the sky as they joyously announce the arrival of Venus.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Centaurs, creatures with the upper body of a human and the lower body of a horse, dance in the water alongside graceful female nymphs.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Two centaurs blow into conch shells further signaling Venus’s birth and arrival.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Bouguereau’s Birth of Venus represents the heights of Academism which was extremely popular in the 19th century, regardless of the rise of Impressionism. The painting deals with a classical mythological subject with idealistic beauty and naturalistic realness. There is truthfulness in the depiction of the waves, clouds, and skin. Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, Honoré Daumier, or Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. His penchant for fictional themes, such as supernatural and mythological subjects, ruled him out. His realm is instead occupied by gods, goddesses, and semi-divine beings.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

Despite being held back from the dirty, ugly, and impoverished side of mortal life, Bouguereau harnessed the psychology of his figures. They interact with and make use of each other, as his depiction of light communicates their textures and forms to highlight their innermost thoughts. Overall, it creates a great charm and sensuality that does not descend into vapid “chocolate box” cover art.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

When Birth of Venus was first displayed in 1879 at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Français, it was declared by the leading Impressionists as spiritually dead. However, with the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the larger public, it became an instant masterpiece There is a cultivated, elegant, and courtly style much valued in 19th-century France in it, which is thankfully being re-evaluated and re-appreciated today in the 21st century. Ironically, Bouguereau and the Impressionist masterpieces now hang alongside each other in the Musée d’Orsay. The two polar opposites speak of what makes great art and together create a broader, more inclusive narrative of French and Western art history.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Birth of Venus, 1879, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Detail.

What Botticelli achieved in the 15th century with his Birth of Venus is what Bouguereau achieved with his Birth of Venus in the 19th century. They are both masterpieces of beauty, sensuality, and drama. Bouguereau breathes new life into a centuries-old subject with his erotic courtesan-like Venus. Bouguereau did not use a courtesan as his model. If not, who was the model, and what could Venus be modeled after?

Wendy Beckett and Patricia Wright. Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces. London, UK: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1999.

“Birth of Venus.” Collection. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

Victoria Charles, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal. 1000 Paintings of Genius. New York, NY, USA: Barnes & Noble Books, 2006.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Marcus Lodwick, Museum Companion: Understanding Western Art. New York, NY, USA: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003.

“Self-Portrait.” Collection. Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Canada. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!