Summary

- Introducing the photographic themes.

- The role of the artist in the photographs: Everywoman, domestic worker, spectator, critic.

- Carrie Mae Weems’s series: Family Pictures and Stories, Colored People, Museums, The Kitchen Table Series.

- Lorna Simpson and the combination of photography and other media

- Zane Muholi’s aim of photography: marking, mapping, and preserving our mo(ve)ments.

Social Awareness

In their photographs, all three artists emphasize narrow and conventional ideas about gender, culture, and race. They focus on Black people, women, and LGBTIQ+ people, who are often marginalized in society. All three artists also appear in their images, playing the leading role. But these are not regular self-portraits. They use their body for something much broader—for instance, to portray the Everywoman and the domestic workers, to construct identities and blur the lines of time, identity, and personal history, and to examine discrimination in artistic institutions.

Carrie Mae Weems

Black feminist photographers: Carrie Mae Weems in 2018 photographed by Mickalene Thomas.

I’m not as interested in my own career as I am in moving a kind of cultural diplomacy forward.

Carrie Mae Weems was born in 1953 in Portland, Oregon. The series titled Family Pictures and Stories portray the everyday life of her own African American family and were part of her MFA graduate show at the University of California, San Diego in 1984. In 1987, she obtained an MA from the University of California, Berkeley. In addition to photographs, she also employs text, fabric, audio, digital images, installation, and video in her work. In 2014, she became the first African American woman who had a solo exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. She has since participated in numerous exhibitions and received numerous awards.

Black feminist photographers: Carrie Mae Weems, Vera; from Family Pictures and Stories. Artist’s website.

In the Colored People series, she interrogates what is the range of skin color “black.” It is a beautiful composition of 11 black-and-white portraits of African American adolescents in prints and 31 colored clay papers. The prints and the papers of the same dimension, arrayed in an irregular sequence, form a grid. The work shows balance, chromatic interactions, difference and diversity, individuality, and social and political implications of color. Boys and girls in the photos are, as Weems puts it, at an age “when issues of race really begin to affect you, at the point of an innocence beginning to be disrupted.”

Black feminist photographers: Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Colored People Grid), 2009-2010, Kemper Art Museum, Kansas City, MO, USA.

In the Museums series, Weems explores inequalities in artistic institutions. In her photographs, she appears in front of art institutions in a long black dress with her back turned to the camera. This elegant silhouette symbolizes the longing for admission and a distance from the artists whose works hang within these institutions. In other words, it symbolizes the ever-present inequality in museums and art institutions.

Black feminist photographers: Carrie Mae Weems, The Louvre (from The Museum Series), 2006. Artist’s website.

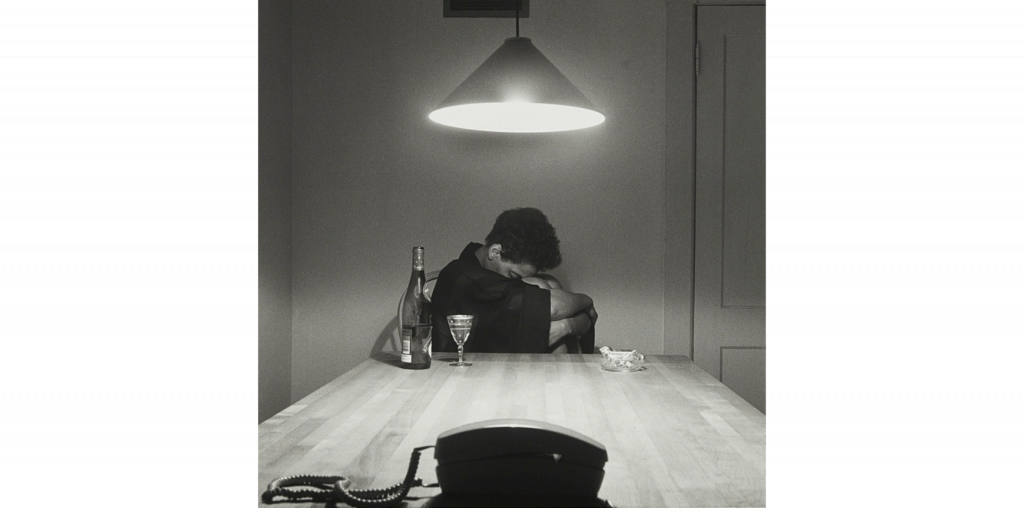

In The Kitchen Table Series, probably her best-known piece, Weems reveals intimate moments and emotions of everyday life. What seems to be documentary photography is actually highly constructive. A wood table, chairs, and a bright lamp, as a universal space, and Weems as Everywoman. The series shows something universal about the experience of many women across cultures.

Again, she includes herself as the subject in the photographs as she lived in an all-white town and wanted to photograph Black women. So, she used her body to stand in for a Black female subject. In Untitled (Woman and phone), a phone is in the foreground. It should be ringing, but it is not. The table leads the viewer’s gaze to the woman, whose position suggests despair and sadness. A half-drunk bottle and a full ashtray further convince us of this impression. The lamp above the table, illuminates the central empty part of the photograph, enhancing the impression of a void.

Black female photographers: Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and phone) from the series The Kitchen Table, 1990. Artist’s website.

Lorna Simpson

Black feminist photographers: Lorna Simpson in 2013, Photograph by George Pitts.

Lorna Simpson was born in 1960 in Brooklyn. She did her undergraduate studies at the School of Visual Arts and has completed her MFA at the University of California, San Diego. She began as a documentary photographer but later turned to conceptual art rooted in photography. In 1993, she became the first African American woman to have her work shown at the Venice Biennale. She is constantly experimenting with materials, media, and methodologies. In her powerful artworks, she combines photographs with words.

Black female photographers: Lorna Simpson, Five Day Forecast, 1991, Tate, London, UK. © Lorna Simpson.

In Simson’s images, African American figures are often seen only from behind or in fragments and capture gestures. The artwork Five Day Forecast consists of five framed photographs showing a repeated photograph of a Black woman. We don’t see her face. She is dressed in a simple white dress and has folded arms. The artist accompanies these images with fragmented text. Above the photographs are the names of the days of the working week. Underneath the photographs are words that use the prefix mis-, which carries a negative meaning, such as misdescription and misidentify. Is this how the artist herself was feeling in the monotonous workplace? What is unseen and left unsaid is equally important as what is disclosed.

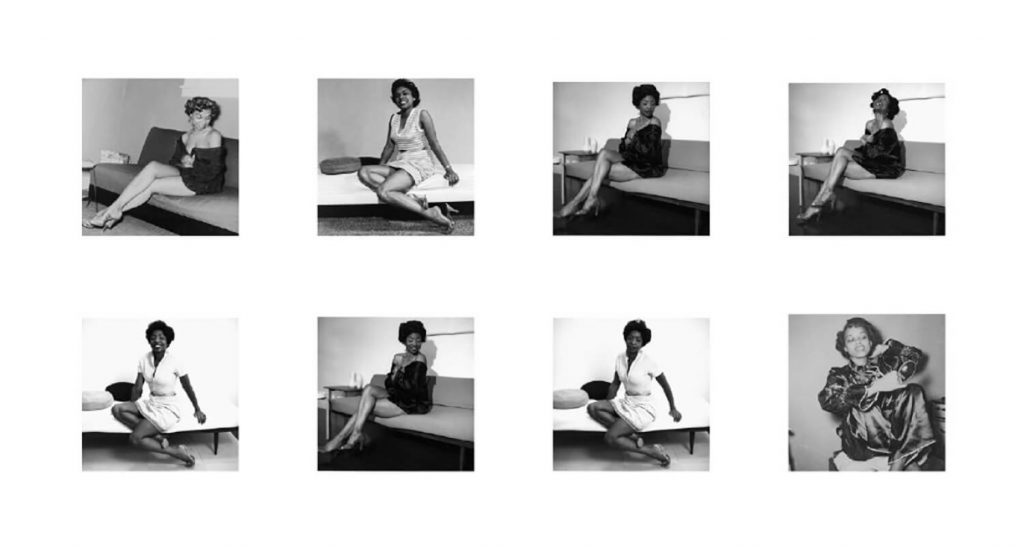

Black feminist photographers: Lorna Simpson, 1957–2009 Interior, 2009, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge, MA, USA. © Lorna Simpson. Detail.

In her series of works called 1957-2009 Interiors, Simpson worked with some found photographs. The artist reenacted the postures of a Black woman posing in a suburban living room in California around 1957, most probably in order to create her portfolio. Simpson reinvented the archived images by imitating and mirroring the poses of the unknown woman. She revealed that: “using appropriated images engages her past work and also engages the appropriation of desire, in terms of the legacies of portraiture, and also of visual information.” This resulted in discomfort that was similar to how she felt operating outside of the scope of her earlier work.

Zanele Muholi

Black feminist photographers: Zanele Muholi. © Photo by Beowulf Sheehan/PEN America/Opale/Bridgeman Images.

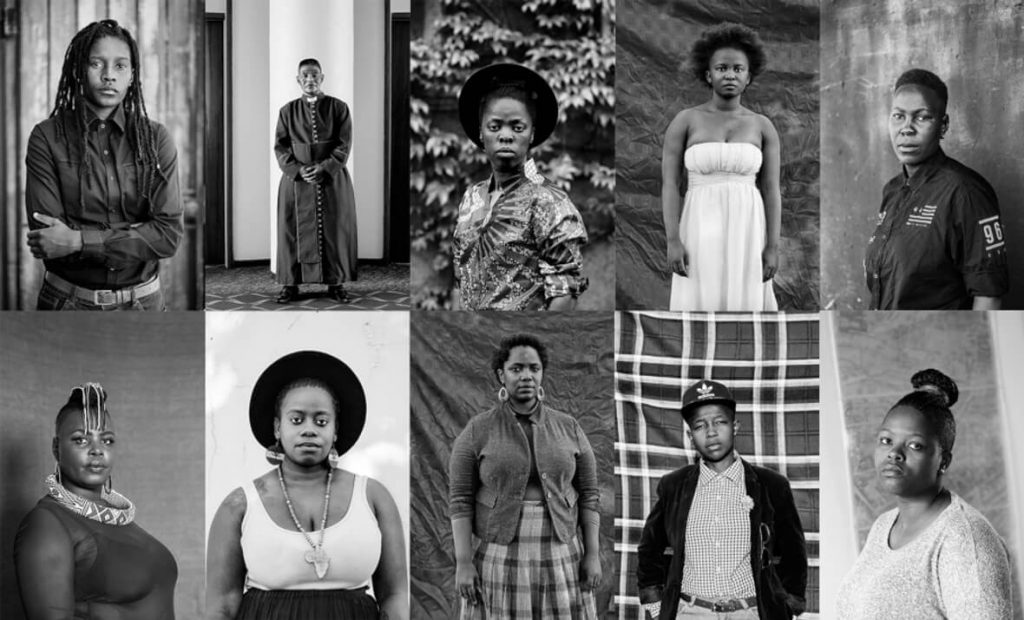

Zanele Muholi is a photographer and visual activist born in Umlazi, South Africa, in 1972. Muholi completed an Advanced Photography course at the Market Photo Workshop in Newtown. Muholi is non-binary and uses they/them pronouns, explaining that they “identify as a human being.” They document Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people’s lives in various townships in South Africa.

It is important to mark, map, and preserve our mo(ve)ments through visual histories for reference and posterity so that future generations will note that we were here.

Especially in their project Faces and Phases (2006–2016), individual black-and-white portraits of Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, and intersex people with stony expressions, Muholi tries to offset the negative attitudes towards the LGBTIQ+ community in South Africa. They capture moods that other people cannot see. So, every portrait becomes one biography and comes with positive connotations. There are many portraits of the same individuals. We see how their age, transition, and presentation of themselves alter over time. The project currently has 500+ works.

Black feminist photographers: Zanele Muholi, 13th edition of Faces and Phases, 2019 at The Stevenson Johannesburg gallery in Parktown North. GQ Magazine.

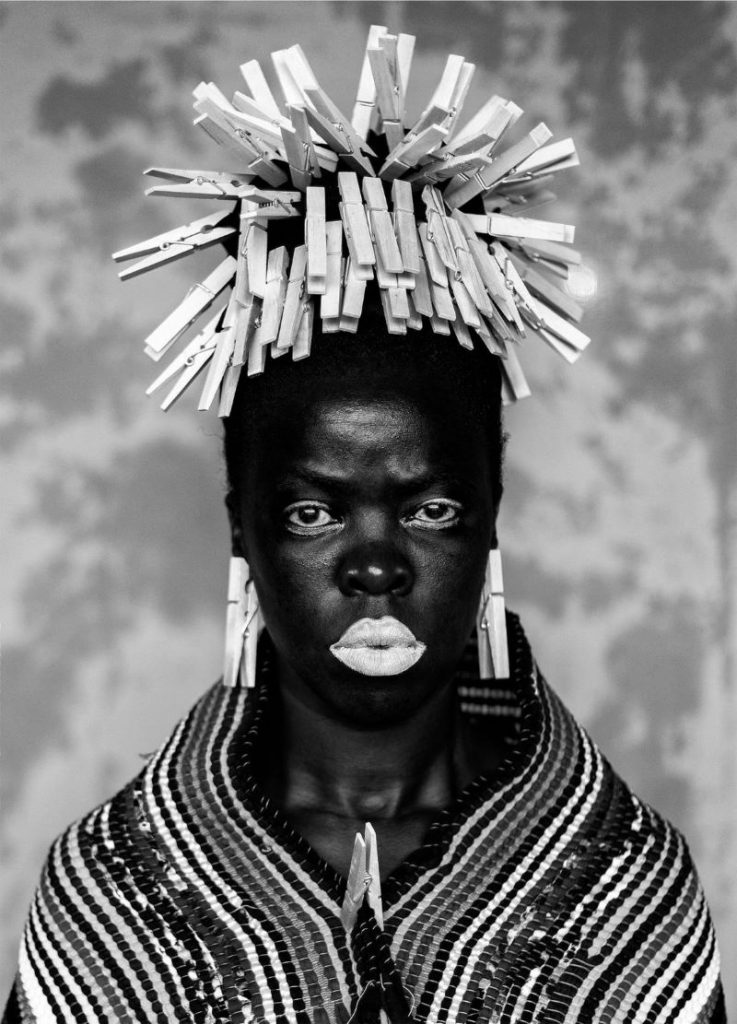

The frontal pose of traditional portraiture is also characteristic of their powerful self-portraits, in which they create different characters using different clothing and accessories. In Bester I, only by looking in more detail does a viewer realizes that those are actually clothespins that are crowing their head, and the fabric on their body is in fact a doormat. With this image, they “looked at how different people can use the materials of daily life for multiple purposes and have dedicated it to all the domestic workers around the globe, who can fend for their families despite meager salaries and make ends meet.”

Black feminist photographers: Zanele Muholi, Bester I, Mayotte, 2015. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York, NY, USA. © Zanele Muholi.

In my world, every human is beautiful. It’s the kindness and what comes from within that is beautiful.

After having documented the painful experiences of so many other people, with their self-portraits they wanted to document the painful experiences that they were going through. And yet, those painful experiences they have faced or gone through resulted in beautiful photographs. The enhanced contrast in the photographs emphasizes the darkness of their skin tone and their beauty. In Ntozake II, Muholi creates a crown of scouring pads. Their eyes are lifted skyward, their neck extended. Muholi said: “Ntozakhe is based on the Statue of Liberty, representing the idea of freedom — the freedom all women should have — as well as pride: pride in who we are as Black, female-bodied beings.”

They position themself in this work as Lady Liberty, honoring the lives of domestic laborers.

Black feminist photographers: Zanele Muholi, Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York, NY, USA. © Zanele Muholi.

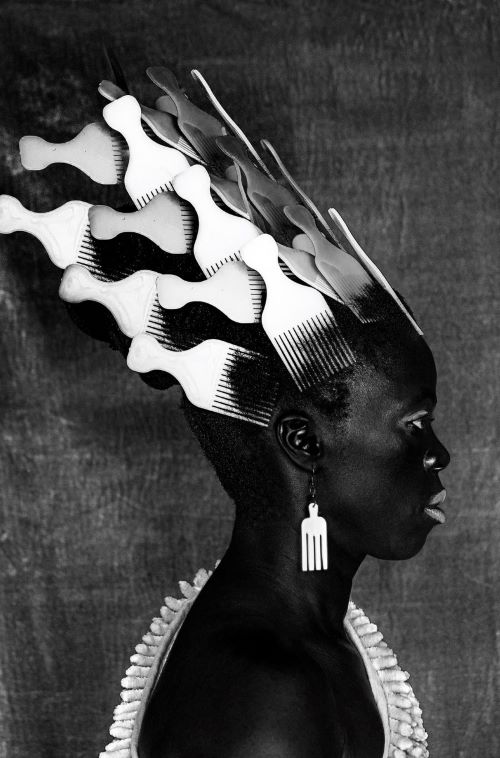

The titles of the works in the series Somnyama Ngonyama (2012–ongoing) remain in isiZulu, Muholi’s first language. This is part of their activism. Somnyama Ngonyama means Hail the dark lioness. There are so many references in these images – to colonialism, apartheid, to the politics of race, femininity, and women’s work. In Quinso, The Sails Muholi’s hair is decorated with silvery Afro combs, a symbol of African culture.

Black feminist photographers: Zanele Muholi, Qiniso, The Sails, Durban, 2019. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York, NY, USA. © Zanele Muholi.

All tree authors are interested in social engagement and represent a moral force. Their incredibly powerful works make us think of how important it is to fight for equality and freedom for everyone.