The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

Portraits of Black people are rare in European art history. Let’s be clear: they were there, in society, but they rarely made it into art, except as colonial trophies. Black people have lived in great numbers across Europe dating back to at least the 16th century. The Romans held thousands of enslaved Africans. But art history does not reflect this accurately, and European art galleries can seem to be the very embodiment of whiteness. To many, high culture is a white European pursuit, and Black bodies are either absent or portrayed in subservient roles. Their humanity and individuality is often entirely denied.

Black models in art: Frédéric Bazille, La Toilette, 1869-1870, Musée Fabre, Montpelier, France.

Thankfully, even if slowly, times are changing, and many institutions are addressing this entrenched absurdity, by looking at their collections, and at how they acquire, curate and display works. But even then we have a problem – the history of Black people in Europe is mostly looked at through the prism of slavery and colonialism, when in truth there is a long shared history between Europe and Africa, going back into antiquity. The plural identities and diverse origins are much more complicated than some would have us believe.

Black models in art: Frédéric Bazille, Young Woman with Peonies, 1870, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Let’s delve into some of the most famous European works showing enslaved people of color. Yes, these works are painful and complicated, and sadly we know very little of the lives of the sitters. Perhaps we must view these images through two lenses – think about what they meant when they were painted, but also consider what they mean to us, at this point in history right now. When we interrogate and analyze the past, perhaps we can envision a time when entrenched racism in our social and political systems has been dismantled for good.

Black models in art: Richard Jeffreys Lewis, The Death of Edward Colston, 1844, Bristol Museums, Bristol, UK.

Almost exclusively, a Black figure in a historical European painting is a prop – an object. They are there solely to frame and reflect the white presence. Rarely are they the focus of the painting. Even Black figures in fine clothing are a kind of lie. The fancy silks and lace are mere decoration covering the reality of a brutal, enslaved life. The costumes serve the purpose of communicating the white owner’s wealth and taste. The Black models (as in the painting of brutal slave trader Edward Colston above) sustain the myth of the faithful, grateful servant and the benevolent master.

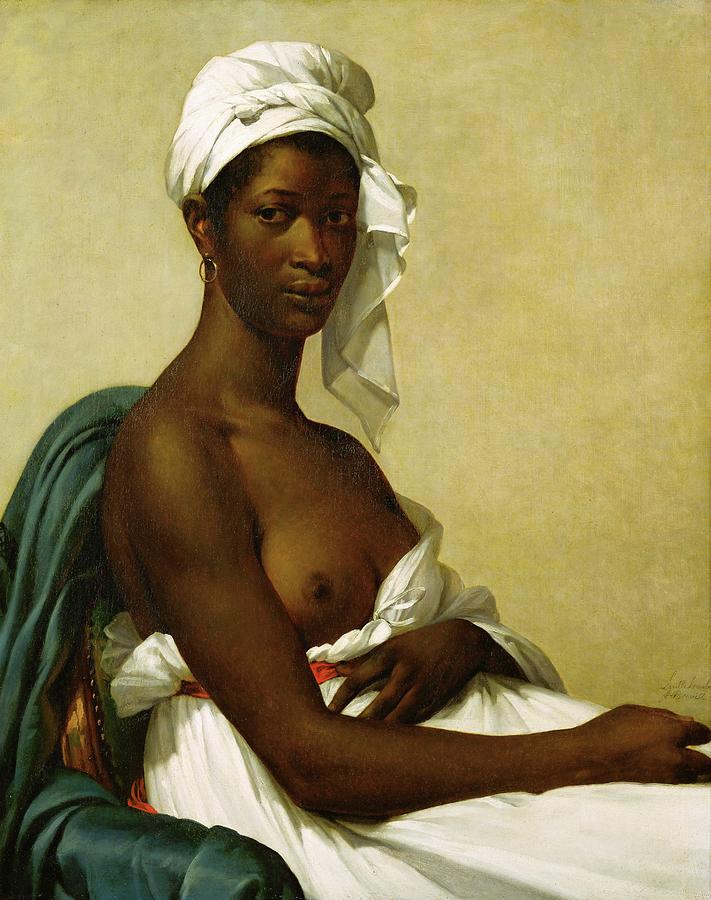

Black models in art: Marie Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine, 1800, Louvre, Paris, France.

If paintings are our records of the past, racial caricatures occur sadly all too frequently. Either that or an indecent obsession with the “exotic” otherness of Black skin. Some galleries have renamed works which contain language we find offensive. But removing racist language does not change the nature of the paintings, which emphasize the subservient role of the Black figure. An example is shown above: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie Guillemine Benoist, originally called Portrait d’une negresse, then changed to Portrait d’une femme noire before finally acknowledging the actual personhood of the beautiful female sitter. Madeleine was an enslaved woman in the French colonies, and she worked as a maid for the painter’s family. Some galleries have even gone as far as scientifically investigating the canvas itself, as in Glasgow, Scotland (below).

Black models in art: Archibald McLauchlan, Glassford’s Family Portrait, 1764-1766, Glasgow Museums Collection, Glasgow, Scotland.

At Glasgow Museum you can see a portrait of the Scottish Glassford family painted by Archibald McLauchlan around 1764–1766. The painting included a Black slave child and a parrot, to symbolize the family wealth made from the slave trade and tobacco. Rumor had it that the slave child was later painted over to hide such shady connections. In fact, curators at Glasgow Museum were able to reveal the boy (who is tucked away behind a grand chair) with x-rays and careful cleaning of the layers of dirt that had accumulated on the canvas. There was truth in the rumor of someone being painted over, however – it was wife number two (Ann Nesbit of Dean) who was painted out and replaced with wife number three (Lady Margaret Mackenzie)!

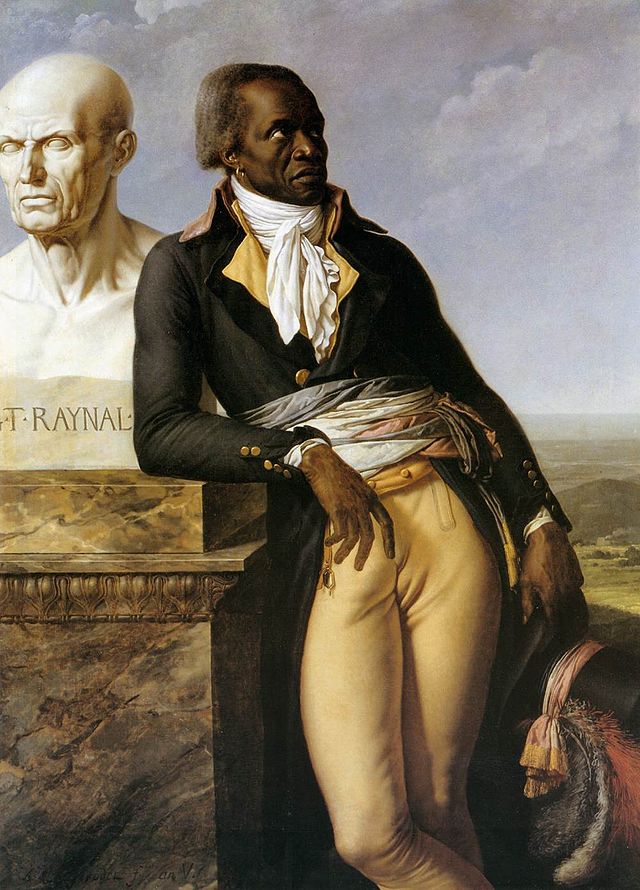

Black models in art: Anne Louis Girodet De Roucy Trioson, Portrait of J B Belley Deputy for Saint Domingue, 1797, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

Click here to read about this painting.

Throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries there was growing opposition to slavery from the abolitionist movement. Now we start to see more sympathetic presentations of the Black sitter – perhaps reflecting a growing recognition of Black people as individuals rather than chattels, worthy of individual representation?

French art in particular has a complicated history with portraits of Black people. France played a key part in the spread of slavery across the globe. Slavery was abolished in France during the Revolution but was subsequently re-established by Napoleon in 1802, who feared losing French colonies. Hundreds of thousands more people were traumatized in bondage and exploitation.

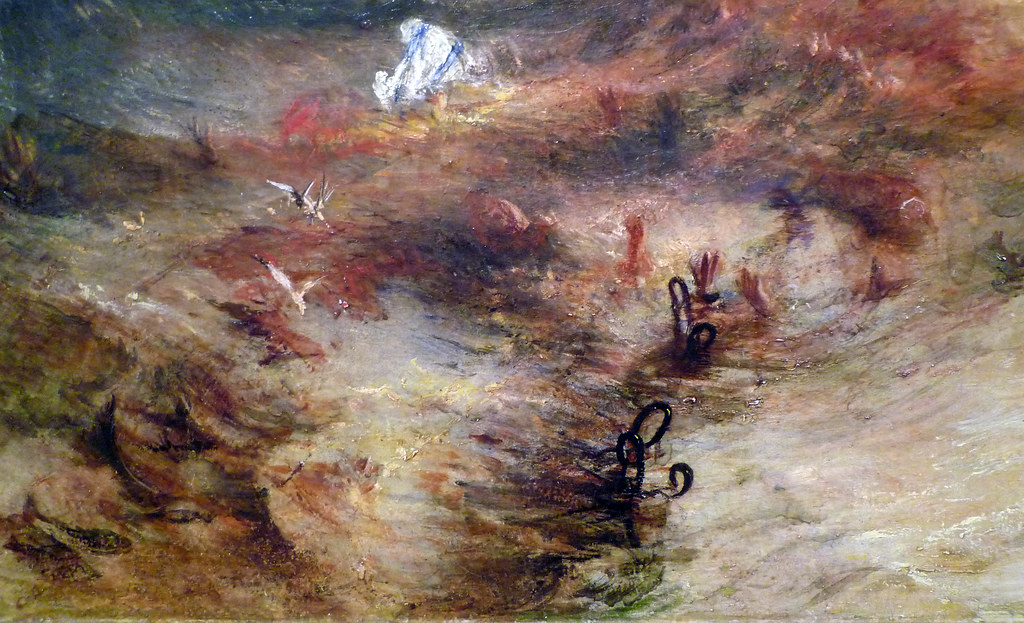

Black models in art: J. M. W. Turner, Slave Ship, originally titled: Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On, 1840, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA. Detail.

As slavery was abolished a second time, in 1848, Paris was a city in social and political flux. It had a significant Black population and was surprisingly integrated. Prominent Black citizens included Alexandre Dumas, made famous by novels like The Three Musketeers, published in 1844. Art in Paris was changing too. A handful of young painters wanted to leave behind the old ways. They yearned to show modern life in all its guises: the commonplace and the real. Enter Edouard Manet, in 1863, with Olympia, which shocked society and art critics alike.

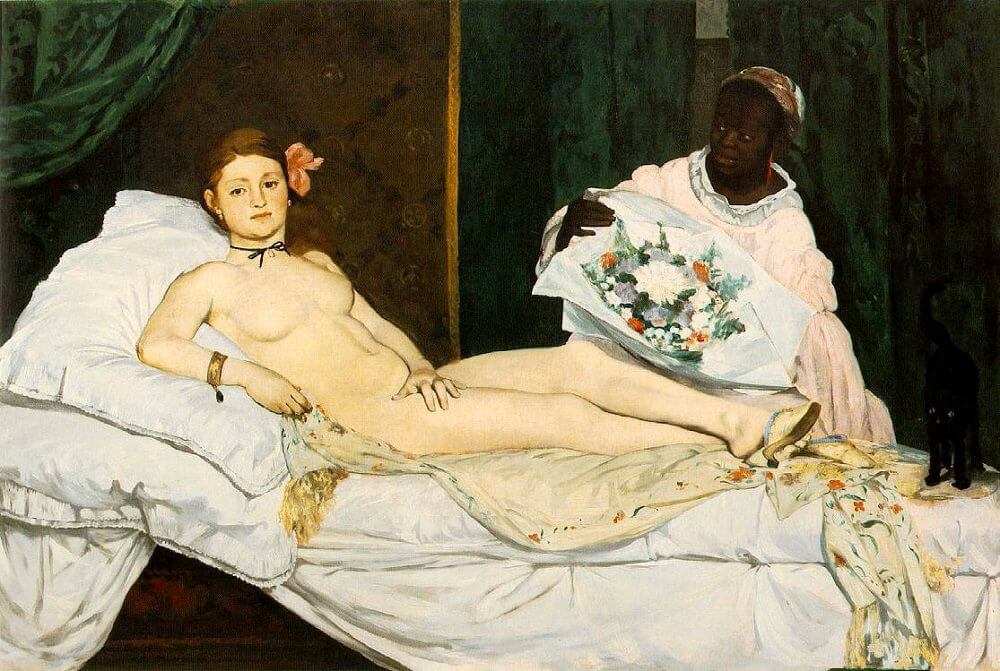

Black models in art: Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Often characterized as the first work of Modernism, Olympia depicts a naked white courtesan and her handsomely clothed Black maid. Laure was the name of the Black model. She lived just 10 minutes from Manet’s studio and he painted her three times. For him, at least, she seems to have been a person, not a mere cipher.

Black models in art: Edouard Manet, La Negresse, 1862, Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turin, Italy.

Manet first painted Laure in 1862 in Children in the Tuileries Gardens. He followed this up with La Negresse the same year. Although the portrait is obviously a woman he knows well, Manet still insists on giving her a generic title. However, a year later, Manet gives Laure a very particular narrative role in Olympia Are we possibly breaking away from the cliches? Perhaps, but this painting is still a product of its time. Both women are “real”, yet both live a life of servitude, albeit in different ways.

Black models in art: Nicolas de Largillière, Portrait of a Woman and an Enslaved Servant, 1696, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

In 1992 Lorraine O’Grady wrote a polemical essay Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity. She lambasted the use of Black bodies as mere symbols to throw whiteness into sharper relief.

Almost 30 years later, in 2019, Denise Murrell organized and curated an international exhibition called Posing Modernity. She had sat through innumerable art history lectures where white subjects were the sole focus. In particular, she knew that historians had spent years poring over the significance of the white prostitute in Manet’s Olympia. But still no-one was particularly interested in the Black maid in the background.

Murrell tried to discover more about the model for the maid and other women like her: Black anonymized figures, left out of academic and artistic discourse. Her PhD dissertation explored this, from Manet to the modern day, and her much lauded exhibition grew out of this research, followed by a book.

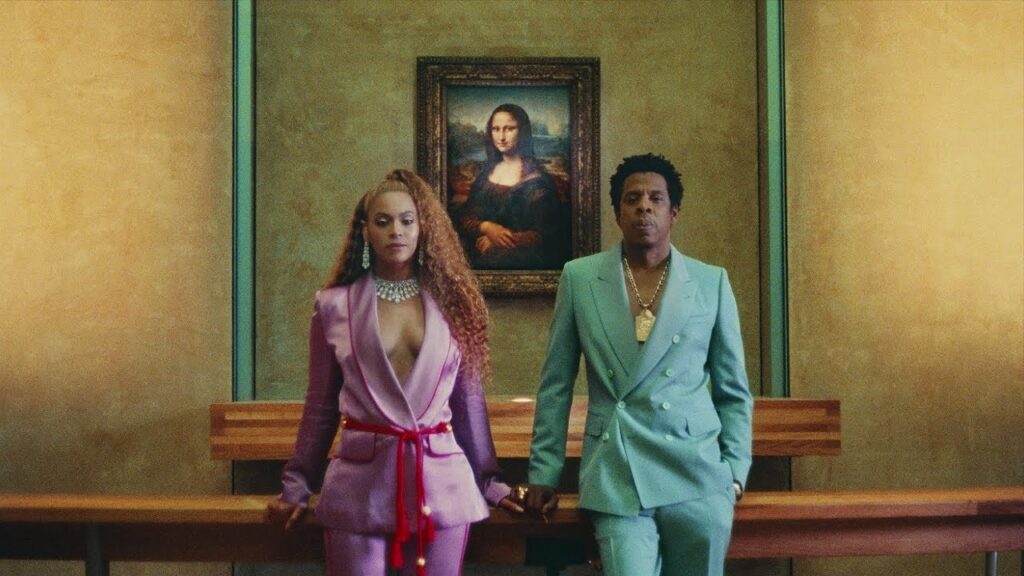

Black models in art: The Carters, Beyonce and JayZ, Apes**t. You Tube.

One year before Posing Modernity drew international interest, superstars Jay Z and Beyoncé were in Paris, filming Apes**t inside the Louvre, the world’s most visited museum. This ground-breaking music video, watched by millions, references the legacy of slavery, but also hints at the long history of Black civilizations. This is a neat circle. We have gone from the original Louvre, fortress and Royal home, which was used to house the exclusively white Royal Collections for the elite to view, and we end with Black musical royalty, storming this bastion of art and culture.

Black models in art: Théodore Géricault, Portrait Study of Joseph, 1818–19, Getty Centre, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

There is still under-representation within the contemporary art scene. There is a lot more to do. Black artists today show us incredible narratives of Black life. There is a diverse range of artistic styles, perspectives and personalities, revealing complex and fascinating art. We see representations that might be political or personal (or both) but whose presence simply cannot be ignored.

Many more stories of the anonymous Black figures in the European art canon are emerging: some might sadden and pain us. But some can excite, surprise, and thrill us. These revelations will reshape and challenge the way we view art history. We must gather and share these stories, and we must support the galleries and curators who are bringing these out into the public sphere, allowing us to finally hear the voices of enslaved people.

A. Bardon. Olivette Otele: “The history of Europe’s blacks has been struck by a partial amnesia.” UNESCO.

E. Mills. Lubaina Himid: Naming the Un-Named. History Today, 12 Dec 2017.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!