Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

3 March 2022 min Read

In Northern Italy, in Turin, you can find the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Foundation, one of the most interesting Italian spaces dedicated to contemporary art. The exhibition, Stretching the Body, which ran there in February, made me discover 12 female artists who deconstruct the traditional female body representation in art through painting and suggest new perspectives. In this article, I want to introduce you to the artists whose visions impressed me the most.

Photo from Stretching the Body, exhibition, 2022, Fondazione Sandretto, Turin, Italy. Photo by the author.

These artists have different origins, ages, and artistic styles, but what they have in common is a desire to break away from the established women’s body representation in art. They want to depict their bodies without the conventional and artificial structures imposed by the white-cishet-male gaze, enacting a work of decolonization and reflection on current issues.

What is interesting is that all the artists use the traditional artistic medium, painting, to show visions that aim to overturn the customary ones. In this exhibition, there were no sculptures, video art, or artistic installations, but only paintings on white walls in very large rooms. This exhibition method makes you focus on the innovation of the representations and on the topics covered, as well as on the differences between the various artworks and artists.

Therefore, the paintings were placed in two different rooms. In one, there were paintings that investigate the relationship between body and space, while in the second one, the artists deform the human figure and rebuild it into new perspectives.

I chose only a few artists from Stretching the Body to talk about. But it is a subjective choice, so I suggest you read more about all of the artists here because they are all worthy of recognition and they may give you different impressions from the ones they gave me!

Jill Mulleady’s painting was one of the first you could see entering the exhibition. It is divided into two parts that depict the same setting, but in separate moments, as we can notice from the different positions of the black cat.

Jill Mulleady, Interior, 2019, from Stretching the Body, exhibition, 2022, Fondazione Sandretto, Turin, Italy. Photo by the author.

The artist represents five characters, four in the left painting and one in the right, but we don’t know who they are or if they have any kind of relationship. The only thing they have in common is the room they were put in and the cat. This lack of interaction between the subjects creates an atmosphere of alienation, silence, and loneliness that seems to recall the one in Edward Hopper’s works. The only relationship the characters seem to have is with objects, as each one of them is shown in everyday activities, such as putting contact lenses on or smoking. Because of that, the viewer almost feels like an intruder in the life of someone else. But this feeling is mutual, as the girl with the black t-shirt looks like she is taking a picture of the viewer with her phone.

Jill Mulleady, Interior, 2019, from Stretching the Body, exhibition, 2022, Fondazione Sandretto, Turin, Italy. Photo by the author.

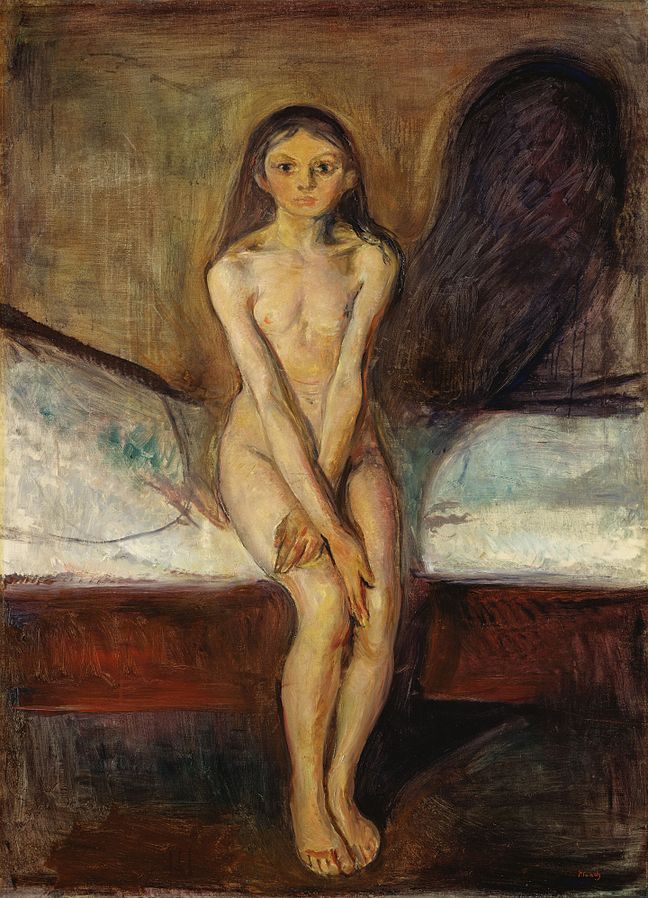

What makes the scene even tenser is a series of details that you may not notice at first. For example, the window behind the man shows a blurry view that makes the whole scene hard to locate. Also, if you look at the mirror in the painting on the left, you can catch a shadow behind the woman who is getting ready. It is difficult to understand if it’s her own or there is someone behind her whom we can’t see. It is very reminiscent of the shadow behind the girl in Edvard Munch’s Puberty.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1895, Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway.

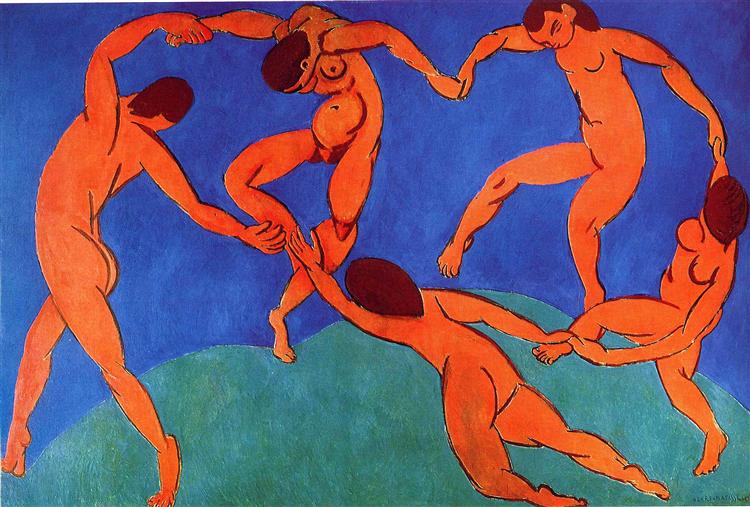

In her artworks, Mulleady often recalls art history in an ironical and unpretentious way, combining the past and contemporary society. Doesn’t the painting behind the woman remind you of a more twisted Henri Matisse’s La Danse?

Henri Matisse, La Danse, 1910, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Another artist depicting body representation in art. The cubic-shaped figures in Mernet Larsen‘s paintings live in artificial worlds where traditional perspective is reversed and distorted. The artist captures a moment as it happens in photography but makes the scene itself become a combination of parts whose mechanisms are clear to the viewer.

Mernet Larsen, Nativity, 2005, from Stretching the Body, exhibition, 2022, Fondazione Sandretto, Turin, Italy. Photo by the author.

There are many influences on Larsen’s vision: one of them is the Renaissance narrative painting. What is impressive is how her art adapts the symmetrical and neat structures of the past art to the contemporary world, which comprehends countless points of view and can sometimes give you a sense of vertigo and unsteadiness.

For example, Nativity is inspired by 15th-century Sienese paintings, but the narrative is very different. The Angels who are supposed to protect the baby look like concrete monuments precariously hanging above his head, and the gold of their wings, which reminds one of the backgrounds from Medieval altarpieces, make them look even heavier.

Benvenuto di Giovanni, The Madonna and Child, late 15th century, Colle del Duomo Museum, Viterbo, Italy.

Meanwhile, the woman who is supposed to be Mary, who is usually depicted as a young and calm lady holding the baby, is sitting, giving him her back, and looking contrite. The baby is left alone in a crib that looks more like a coffin, and his crying, violaceous face is the only realistic detail of the painting. We can say that the whole scene seems to represent a mournful death, more than a glorious nativity.

The art critic Isabelle Graw wrote that Jana Euler:

…makes the sometimes-excruciating restraints it imposes visible and explicit, performing a black comedy of accommodation.

“Social Realism: The Art of Jana Euler”, ArtForum, Nov 2012.

That’s exactly what happens in her painting, where the naked female figure is completely deconstructed and rebuilt around a white void. The observer can see the woman almost from every point of view but in a biased and twisted way. So, the woman loses her individuality and becomes a series of human parts randomly attached to a body at the mercy of the viewer.

Jana Euler,“” (body (blackvoid)), 2016, from Stretching the Body, exhibition, 2022, Fondazione Sandretto, Turin, Italy. Photo by the author.

In the meantime, though, the observer becomes the one who is being observed. The angry brown eyes on the upper part of the painting seem to be watching the viewer. They give the figure her humanity back and make her become a subject, and not anymore an object we can look at undisturbed.

Here are the names of other artists present at the exhibition, with links to their pages, so that you can learn about them and “stretch” your mind with new visions on body representation in art: Giulia Andreani, Louise Bonnet, Jaclyn Conley, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Wangari Mathenge, Christina Quarles, Avery Singer, Anj Smith, and Ambera Wellmann.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!