Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

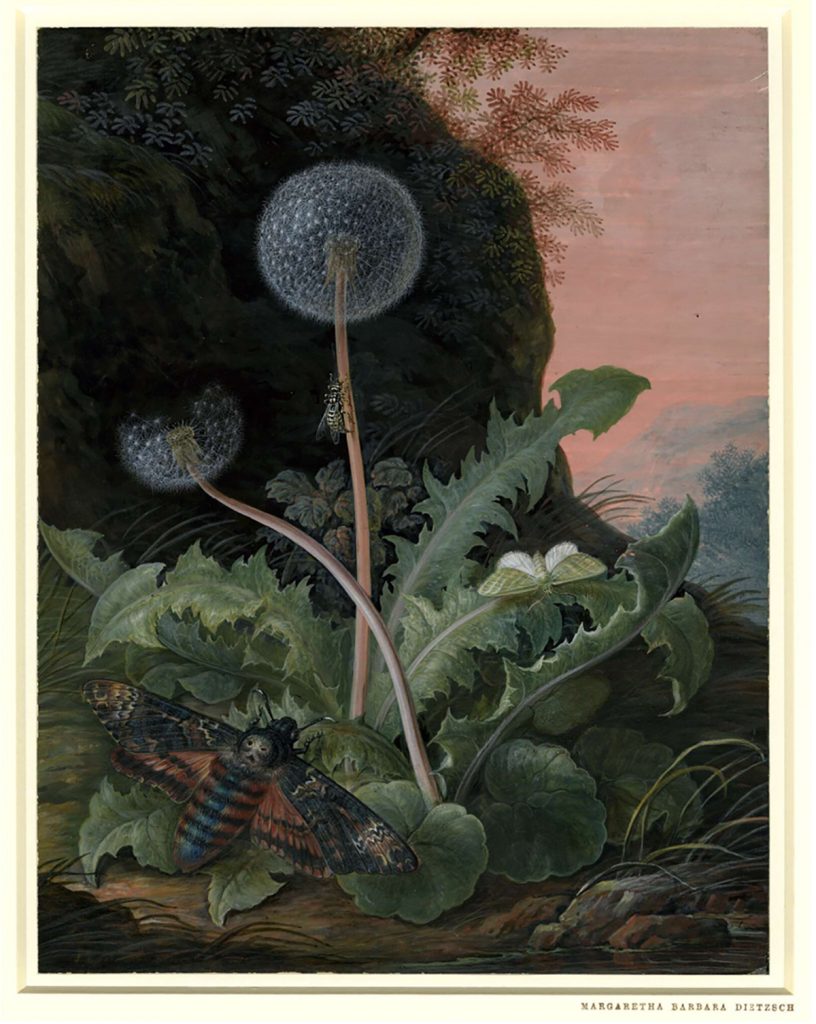

Bavarian-born Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706–1783) was one of the finest botanical artists and engravers of her time. Her work was unparalleled for its delicacy of execution and hyperrealistic detail. When we look at her work, we enter a world of gauzy, spiraling formations and precise biological observation, brought together to form exquisite paintings of often extremely transient subjects. Let’s have a look at the botanical art of Barbara Regina Dietzsch.

Building on the work of artists who went before her, for example naturalist and illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), Dietzsch took this particular field of art beyond the remit of the scientific diagram. She set a benchmark for excellence that has influenced botanical artists ever since.

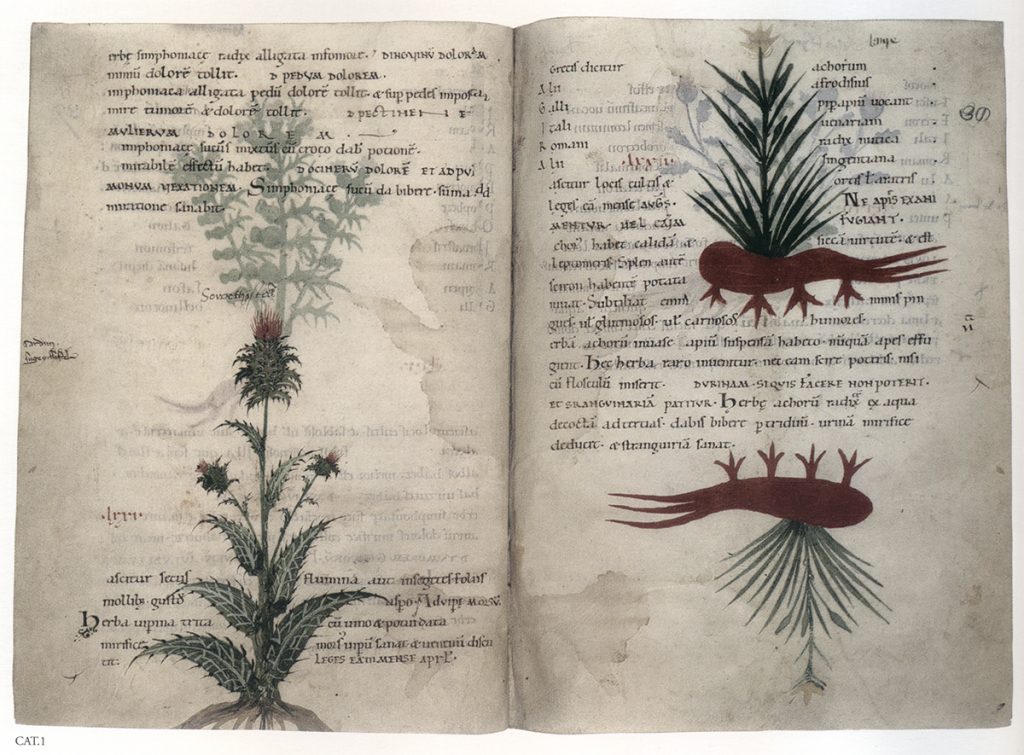

The earliest botanical works were herbals. These were manuscripts containing the names, medicinal properties, locations, and of course the appearances of various plants. Doctors and apothecaries used herbals as guides to the properties and applications of different flora. They became the blueprints for later works on the subject of botany in medicine.

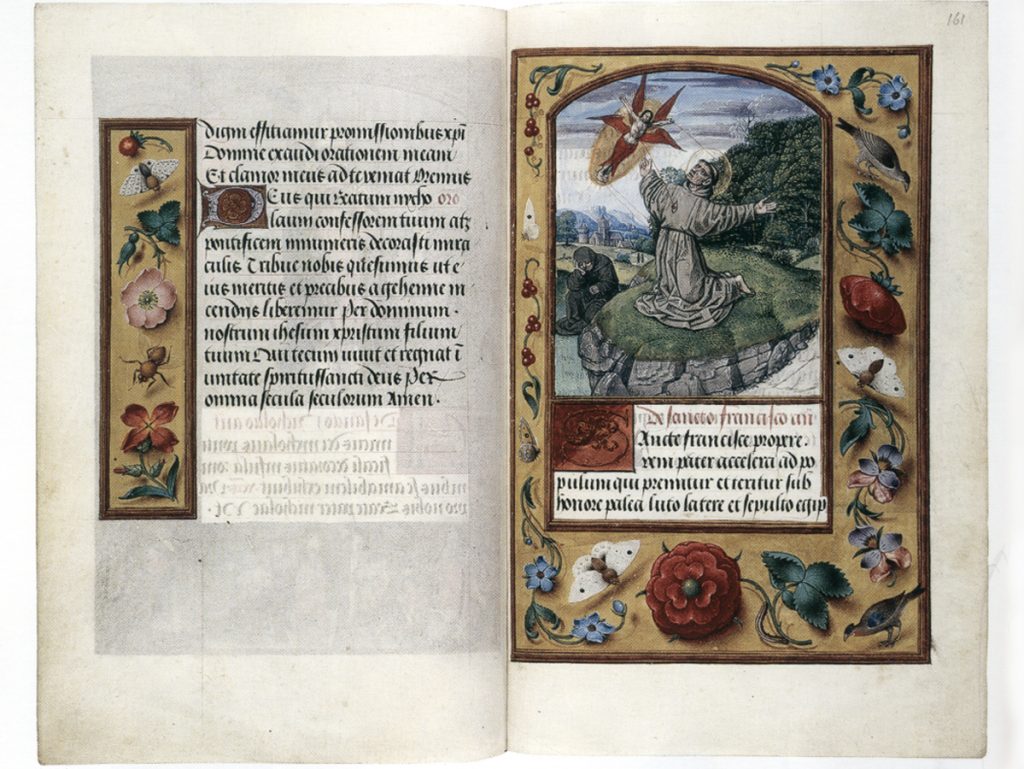

Plants not only had practical value, but were also seen as objects of great beauty, often with symbolic significance. They were often found, for example, adorning the borders of books of hours.

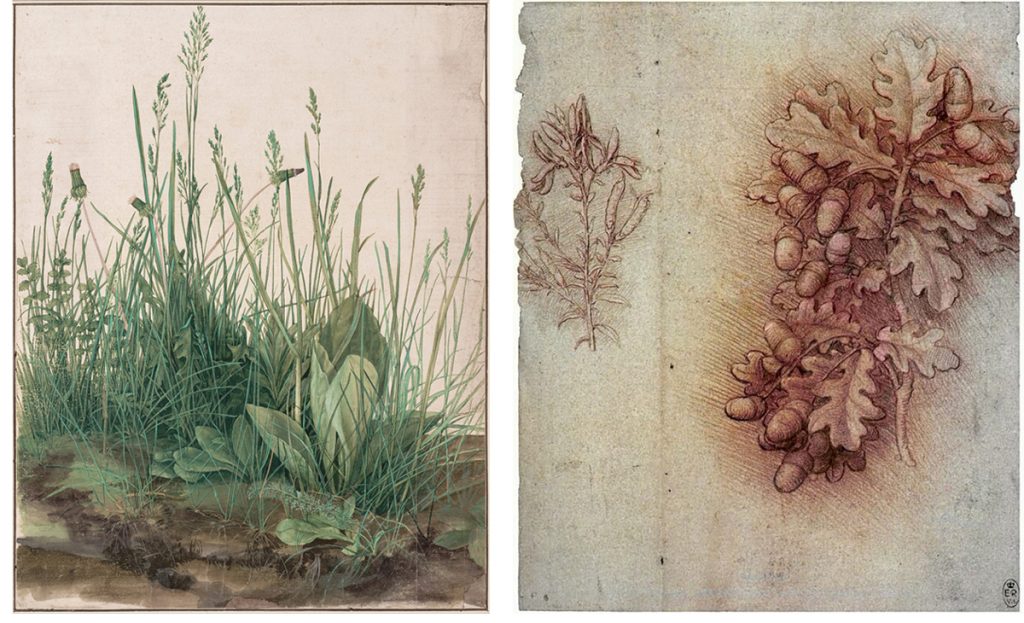

Nature was observed as a matter of course by artists painting in vivo. That is to say, flowers and other plants were studied, often with attendant beetles, butterflies, or other insects. Both Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) observed and produced studies from nature. It was a practice which was seen to be invaluable in the development of technical artistic skill.

It wasn’t until the beginning of the Scientific Revolution, towards the end of the Renaissance period, that the artistic reproduction of plants, or botanical art, became a pursuit in its own right. The need for more accurate and extensive catalogues of flora became of great importance. It was particularly important for those who either observed or collected in foreign and unfamiliar parts of the world. Plants in every variety began to occupy the realist artist’s time. The closer to faithfully reproducing nature a draughtsman could come, the better. The botanical art of Barbara Regina Dietzsch is an outstanding example of this practice.

By the time of the 17th and 18th centuries, botanical art had become more than the reproduction of detailed drawings for inclusion in an ever-growing reference library. It had transformed into a genre of its own. Botanical painting had its roots in antiquity, but by the time of Dietzsch it was reaching its summit – a period of artistic and technical excellence in the field.

The botanical art of Barbara Regina Dietzsch is impeccable in its execution, even with materials that would now be considered to be old fashioned. She possessed a technique so refined and linear, as might be expected from an engraver. She was able to render even the most diaphanous and flimsy flower in an unearthly way. As a result, Dietzsch set a high standard for other artists to meet.

When we talk about other botanical artists following in her footsteps, we can include Dietzsch’s sister, Margaretha, whom she taught to paint. Margaretha Barbara Dietzsch (1726–1795) also focused on botanical subjects, predominantly fruit and flowers, but also enjoyed drawing birds.

It would be remiss not to mention Ernst Friedrich Carl Lang (1748–1782), for whom the botanical art of Barbara Regina Dietzsch was a great inspiration. For example, her influence can be seen in his renditions of flowers and insects. His attention to the transience of petals, the frailty of butterfly wings, and the overall fragility of his subjects, demonstrates the same respectful attention to detail which we find in Dietzsch’ work.

The whole Dietzsch family was involved in essentially the family printmaking business. Barbara’s father was Johann Israel, an artist employed by the Nuremberg City Courts. One of her brothers – Johann Christoph (1710–1769) – had similar employment. Below are two thistles: one Barbara created (left) and another Johann created (right).

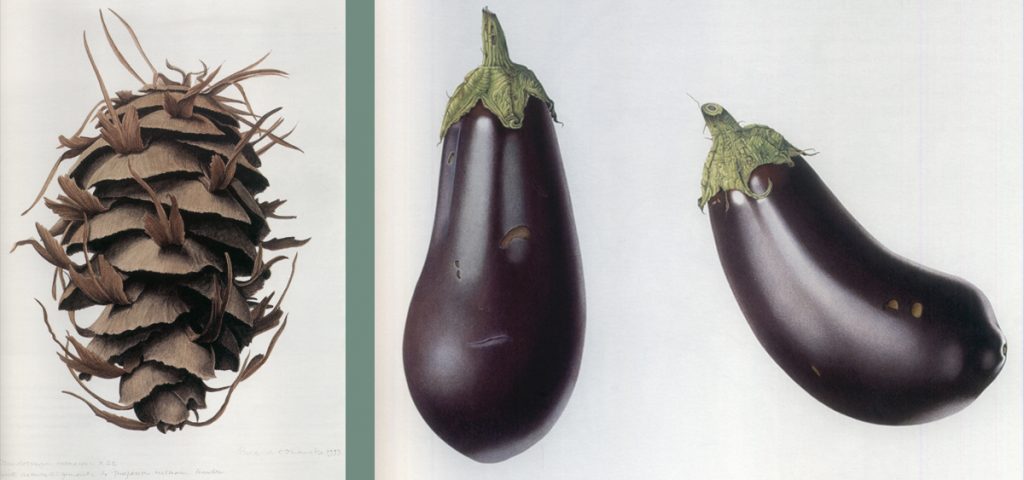

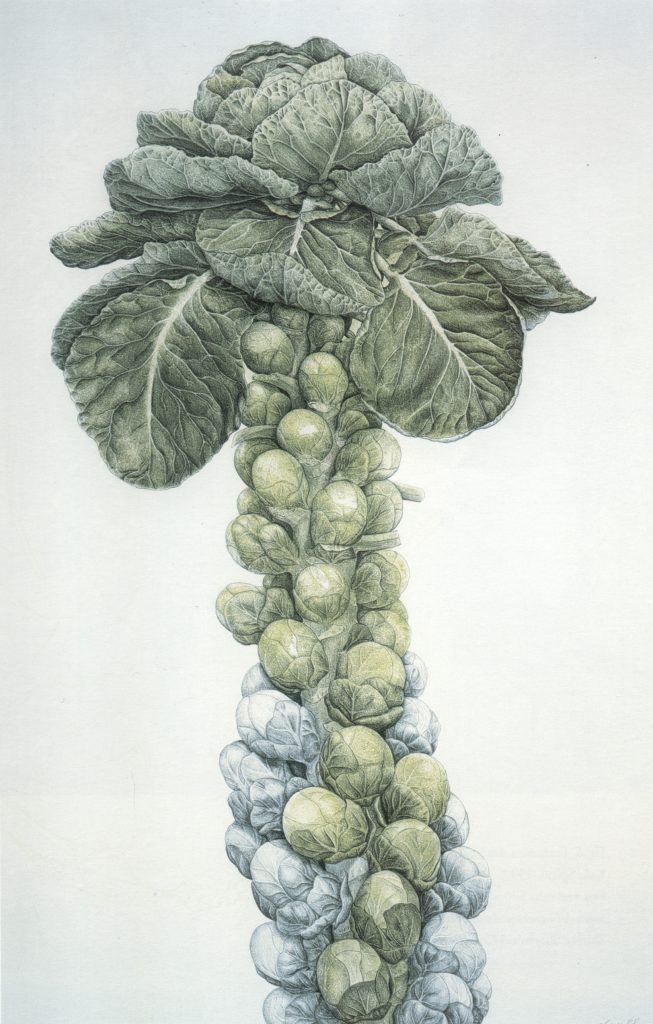

Dietzsch beautifully reproduced even the most complex botanical formations accurately enough for scientific record. However, they were works of art entirely in their own right as well. The genre of botanical art has remained popular. Artists such as Brigid Edwards, Ann Swan, Pauline Dean, and Susannah Blaxill have produced paintings of botanical subjects ranging from Brussels sprouts and eggplants, from pinecones to mushrooms. Botanical art isn’t only about what we consider to be traditionally pretty – a notion that has possibilities in other genres perhaps?

Enjoy the following pictures!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!