Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

There are many social, political, scientific, and economic models that are embracing the idea of the “both/and” philosophy. It is my contention that artists are ahead of the game with this, and have pretty much always based their work in this messy but very human arena.

Both/and is an idea that embraces paradox. From the ancient Chinese yin-yang model right up to quantum physics. Either/Or logic is, however a more rigid construct, very firmly entrenched in Western minds, it states two opposite claims cannot both be true at the same time, in the same sense.

I would like to present Glenys Barton as an example of how working at the boundary where opposites co-exist (or even collide) can produce the most thoughtful sculptural forms.

Like me, Barton was a working-class Midlander. She was born in 1944 in the industrial town of Stoke-on-Trent, where her family was employed within the potteries. Her schooling was uneventful, and her artistic talent seems to have been suppressed. A short stint at teacher training didn’t suit, and instead, she trained as a dancer, finding a creative outlet through the Laban school. Laban aims to describe the place of the figure in space. A perfect route to figurative sculpture perhaps? Except so many of Barton’s sculptures are of still and contemplative heads. And so the paradox begins.

She arrived in London in 1968 to attend the Royal College of Art. Once there her work developed quickly and she had several international shows within a few years.

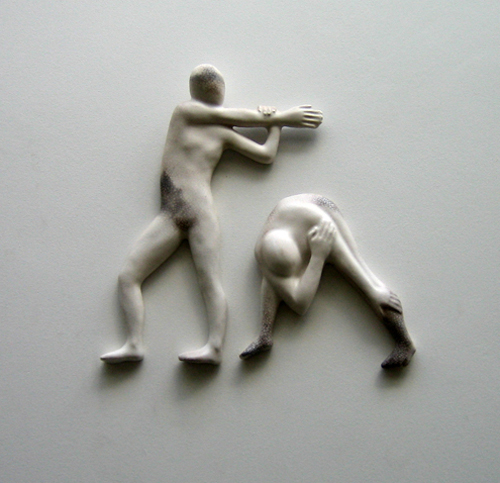

Her early work seems deeply connected to the past, to ancient civilizations. We see Egyptian and Indian influences, as well as Greek, Roman, Chinese, and Mexican. She explores general emblematic themes of humanity and the universal everyman. These figures are small, passive, and marionette-like anonymous figures, devoid of hair or lines, often androgynous as if even to mark their gender is too personal. They have the archaic smile of 6th century Greek sculpture, expressing a “mood” rather than portraying an individual.

My subject is always humanity: sometimes a specific human, sometimes human relationships, sometimes human society. The forms may be heads, parts of figures, whole figures or figures within figures. Heads and Hands particularly fascinate me. As I work I feel that I am directly linked with those who have tried to fashion the human form from the earliest times. My greatest achievement would be to create a timeless image.

Glenys Barton, artist’s website.

Barton seems obsessed with creating the perfect form, pushing technique to the limit using the most complex materials. Bone china was the staple product of her hometown, but in modern times is more frequently associated with commercial, functional objects. In the spirit of contradiction, it seems fitting that she moved back to Wedgwood in the 1970s to explore abstract human themes through an almost fanatical obsession with precision in that most unyielding of materials.

From this artistic/industrial processing, she moved to hand-modeled pieces, using plaster molds and slip casting. Her flattened reliefs take influence from the Renaissance frescoes, and later Cézanne, Modigliani, and Picasso.

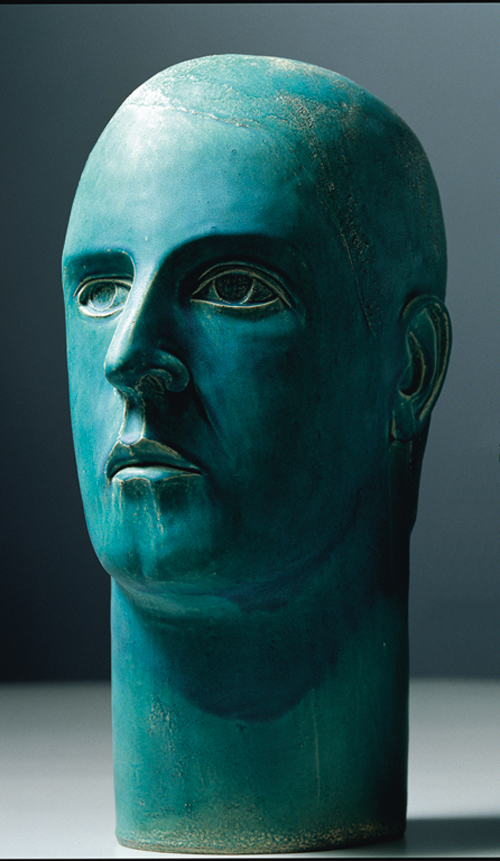

From the early 1990s she moved to portraiture, to the specific, to the intimate. These sculptures dramatically increase in size, sometimes 2 or 3 times life-size – we are literally up-close and personal. But for most of these we still often see closed eyes, serene smiles, and a Buddha-like inward-looking contemplation. Her sculptures do not meet you eye to eye, they are self-absorbed objects, languid, perhaps melancholy yet also peaceful. They are not absent or distracted, however – in particular, the enlarged ears on many heads such as Boccioni II suggest a listening presence.

The late 1980s saw an introduction of color and rough texture, reminiscent of weathered bronze. Her Green Warrior pieces reference environmental issues.

The double-headed works of the 1990s nod to the multi-faceted sculptures of Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist gods. They demand that you move around them and look inside them: here it is the viewer who is invited to imitate the dancer’s fluid movement.

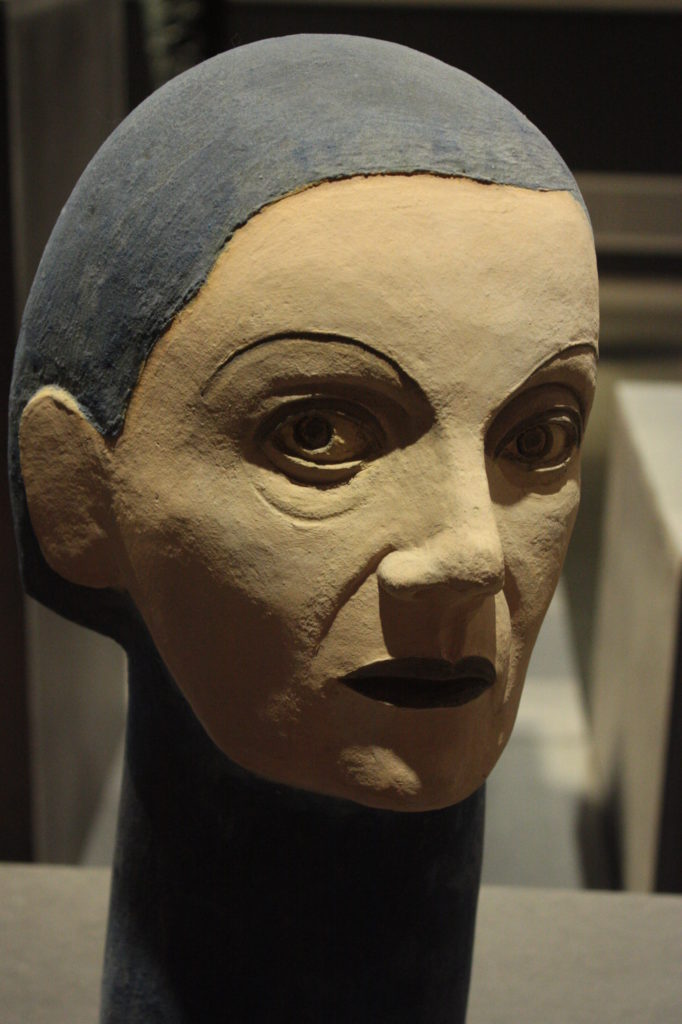

From here on we see a lively and sociable interest in portraying particular humans emerge. These portraits, however, are not slavish reproductions of physical features, rather they recreate a feeling of the person, trying to encapsulate their character.

Barton became more widely recognized in 1993 with her Jean Muir sculpture. We see Muir’s characteristic hairstyle, graceful pose, elegant dress, and her characteristic habit of putting her hand to her face. It was shown in the Portrait Now exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London and was used as the lead publicity image for the exhibition.

In 1993 Barton produced a number of Glenda Jackson pieces Glenda and Gudrun. This double-headed piece fits superbly with the dual role of Glenda Jackson as actress and politician. Sculpting from photographs and film stills, Barton shows two personas bound together in a sculptural curve. Gudrun, the film character is flattened, smaller, on the left, slightly behind the bold intelligent, high-relief Glenda. Both look out at the viewer. In a cinematic way, so very appropriate to its subject matter, this is meant to be seen from the front, not in the round.

The art world seems to have struggled to pigeonhole Barton, and thus her work is less well known than it might be. Working with ceramics means she can be placed in the “crafter” or “potter” category, which is anathema to the high art world. In her career, she crosses boundaries from the lone artist working in the studio, to the industrial potter, to the fine artist.

But throughout she strives to make her figurative work leave room for dialogue and interpretation. To gaze into the face of one of her sculptural heads is to mourn and to celebrate, all at the same time: Both/And.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!