5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

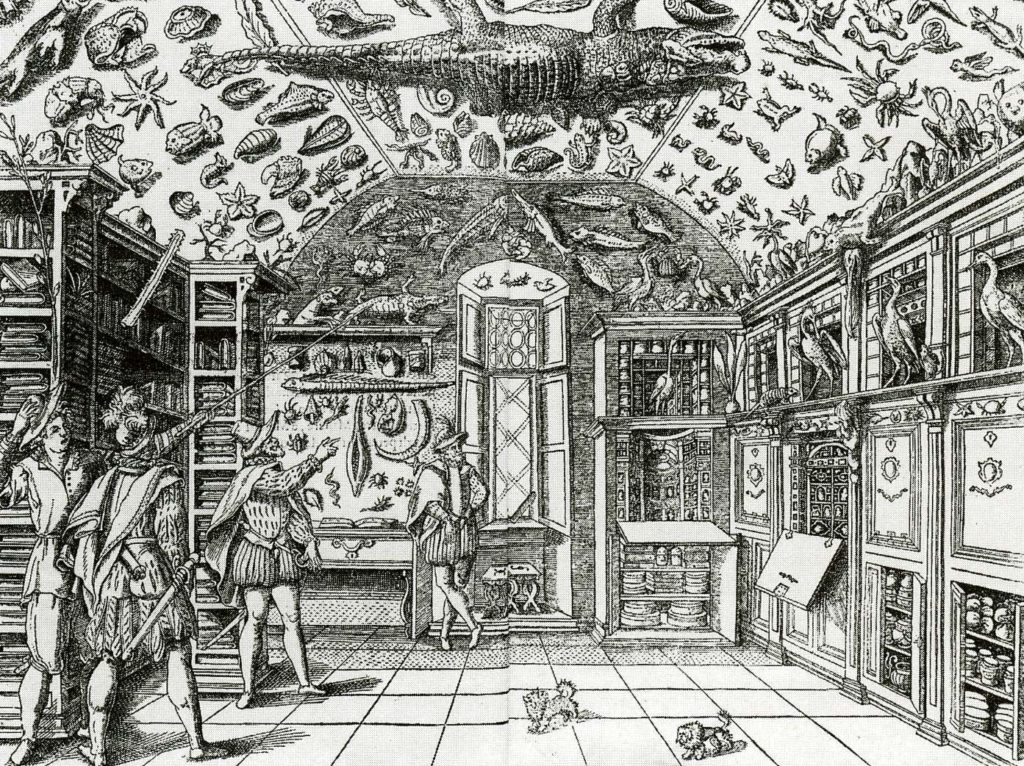

The characteristic of arousing surprise for the observer is typical for the so-called Wunderkammer or Cabinet of Curiosities. These are real rooms of wonders where, in an undifferentiated mix of art and science, of naturalia and artificialia, the most unusual finds are associated with all sorts of man-made works, rarities, and wonders.

This collection typology spread mainly through Northern Europe during the 16th century. Among the most famous collections are those of Rudolf II in Prague, of Emperor Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria in Schloss Ambras in Innsbruck, or of the king of Poland, Augustus III. In addition to cabinets belonging to rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe formed collections that were precursors to museums.

A cabinet of curiosities stored and exhibited a wide variety of objects and artifacts, with a particular leaning toward the rare, eclectic, and esoteric. They commonly featured antiques, objects of natural history (such as stuffed animals, fossils, dried insects, and herbarium) or even works of art. The term cabinet originally described a room rather than a piece of furniture and the collection was usually divided into four categories with Latin taxonomy.

The classic Wunderkammer emerged in the 16th century, although simpler collections existed earlier. The earliest illustration of a natural history cabinet is an engraving from the Neapolitan apothecary Ferrante Imperato’s book Dell’Historia Naturale from 1599. The desire to catalogue every aspect of the natural world led to the creation of repositories of information and images – prints, herbariums, texts with extensive scientific illustrations – and to the birth of places in which to cultivate, preserve, and display them: botanical gardens, pharmacies and naturalistic collections.

Among the oldest naturalistic collections is that of Ulisse Aldrovandi, a Bolognese naturalist. After his death, Aldrovandi donated his entire scientific collection to the city of Bologna. The Museum of Palazzo Poggi in Bologna is a large hall that preserves Aldrovandi’s “Natural Theater”. This was defined as the collection of naturalia that the scholar collected at his home. Today it still amazes visitors with his specimens of crocodiles, puffers, and snakes.

Aldrovandi is also remembered for his famous work, the Storia Naturale, a 13 volume printed work. It was conceived as the most complete description of the three kingdoms of nature – mineral, vegetable, and animal- available at that time. He also published other works like Herbarium. However, the most well known is Monstrorum Historia or History of Monsters, consisting of drawings of hard to find and preserve animals as well as monstrous creatures that never actually existed.

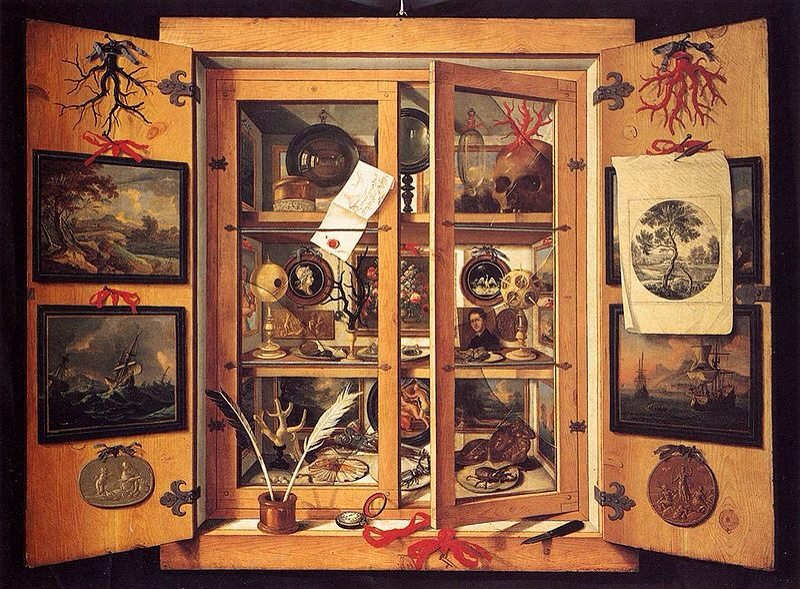

The cabinets ranged in size from something as small as a dedicated piece of furniture with multiple drawers to the size of an entire room. Drawers and shelves housed original objects acquired through long journeys to faraway places. Every object offered an opportunity to tell a story about an epic adventure or, more often, to fabricate one. Like everyone else, the wealthy liked to define their personalities through the possession of glamorous objects as tangible tokens of their intelligence, erudition, wealth, and taste. They had already understood that precious objects held power over people and that associations between luxury items and personality engraved long-lasting impressions.

While north of the alpine mountains these storage rooms were called Kunstkammer or Wunderkammer, on the Italian Peninsula the space housing these objects was called a stanzino, a studiolo, or more often a museo, or sometimes a galleria, a name mostly applied to collections of paintings and works of art that could contain curiosities as well, such as the Medici Galleria. The grandest studiolo was that of Francesco I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.

The Studiolo was completed for the Duke in 1570-1572, by various artists under the supervision of Giorgio Vasari. This small vaulted room was an office, a laboratory, a hiding place but foremost a cabinet of curiosities. Here the Duke kept his collection of small, precious, rare, and unusual objects. The walls and ceiling of the Studiolo were decorated with mythological paintings which are now all that remains in the room of its original contents. Not long after the death of the Grand Duke, it was neglected and dismantled in 1590. Later, in the 20th century, it was reconstructed as a Renaissance oddity in the medieval palace.

Another notable example is the beautiful Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan. It originated in the 19th century as the private collection of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli. The museum is notable for its collection of Northern Italian and Flemish artists. It includes weaponry, glassworks, ceramics, jewelry, furnishings, and much more. During World War II, the building suffered severe damage but the artworks had been placed in a safe storage. The museum reopened after reconstruction in 1951. If you are in Milan, don’t miss the opportunity to see it!

The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, in Prague, was unrivaled and one of the most diverse of its time. The collection preserved various works of art, exotic animals, minerals, lapidary work, and much more. Rooms in the castle at Prague were adapted to store the entire collection divided into different parts. Rudolf II had a special predilection for lapidary work but he was also fascinated by natural phenomena, so he commissioned his court artists to produce paintings of natural objects and animals.

In the inventory covering the years from 1607 to 1611 were listed natural objects such as chameleons, crocodiles, fish, a bird of paradise, and many other creatures. There were even images of unicorns, dragons, and mandrakes in his collections. The Habsburgs were also extremely fascinated by mechanical objects and automatons with moving parts. Rudolf’s successors didn’t appreciate his collection and the Kunstkammer gradually fell into disarray. Plundered in 1648 by Swedish troops who sacked Prague castle, only parts of it remain today in the Vienna collections of the Naturhistorisches Museum.

Rudolf’s uncle, Ferdinand II Archduke of Austria, also had a collection: The Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck. The Archduke, like many other Renaissance rulers, was interested in promoting the arts and sciences and invested time and money to convert his medieval Ambras castle into a contemporary palace to display his unique possessions. The chamber was called also a “microcosm” or a “theater of the world” to symbolize the emperor’s control over the world. The collection continues to be displayed at the castle with the same setting since its establishment.

Two of the most famously described 17th-century cabinets were those of the Danish physician and natural historian Ole Worm (Latinized Olaus Wormius) and the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. In this period a cabinet of curiosities came to signify a collection of works of art which should include objects of virtù or objects and curiosities that a virtuous man would find intellectually stimulating.

Often the cabinets weren’t built on truth. Artifacts, plants, or preserved animals were sometimes purchased and different parts of them were stitched together. The result was the creation of fantastical creatures and monsters, closer to art than to natural evidence. Often they would contain a mix of fact and fiction and were collected from exploring expeditions and trading voyages. Honestly, it didn’t matter though, in spirit these cabinets were not meant to be scientifically accurate. Those who could afford to create and maintain them, could construct for themselves their own version of the world.

By this time, the arrangement of the cabinets was without chronological order or scientific criteria. The owner of a Wunderkammer was fully in charge of the juxtaposition and the interpretation of the collection and the content was a reflection of his taste and identity. However, during the 18th century, the rise of science as a defined discipline meant that collections not only represented the wealth or intelligence of the owner, but also his need to make sense of the world. This is what the human skull on the top shelf of Domenico Remp’s cabinet anticipates: a memento mori or an existential urge to understand life and the knowledge that despite the wealth one might accumulate, death will takes us all one day.

In order to resemble his European rivals, Russian tsar Peter the Great began to collect curiosities like stuffed animals, models of ships, tools, and astronomical instruments. As a result the tsar’s Kunstkamera was established in 1718. Every piece of his collection came from his journeys abroad. One of the rarities included in Peter’s collection were anatomical specimens and embryos prepared by the famous Dutch anatomist Frederick Ruysch. Today the collection is known as the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography and holds one of the largest collections of ethnographic artifacts. This was also the first museum in Russia and one of the oldest in the world.

Sir John Soane, an English physician, member of the Royal Society, and founder of the British Museum in London, while studying plants in England and France was offered a post as a personal physician in Jamaica. While there he was collected and catalogued native fauna and flora as well as various artificial curiosities of native populations.When Soane returned to England in 1689 with over 800 specimens of plants, he began to acquire other collections by gift or purchase from collectors, travelers, apothecaries, and botanists. During his life Soane acquired more than 350 artificial curiosities from all over the world. After his death in 1753 he donated his entire collection to England to form the foundation of the British Museum.

British gardener, naturalist, and botanist John Tradescant the Elder and his son had a very similar destiny. The Tradescants collected flowers, shells, and plants. Besides botanical and zoological specimens, they also collected a variety of natural and artificial curiosities, for example a dodo bird from Mauritius. In their collection false rarities can also be found, like a mermaid’s hand or a dragon’s egg. In 1630, father and son displayed their collection at their residence calling it the Tradescant’s Ark. It became the earliest cabinet of curiosities in England open to the public.

Collector, chemist, antiquarian, and neighbor of the Tradescant family, Elias Ashmole, acquired the Tradescant Ark in 1659. He added it to his collection of astrological, medical, and historical manuscripts. After sixteen years, in order to provide a suitable building for his artifacts, he donated his library and collection to the University of Oxford. The Ashmole’s donation constituted the foundation of the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford.

However, the largest portion of the Tradescant collection passed to another very interesting museum – the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, established in 1860 with seven million objects and more than 30,000 zoological specimens. The Museum is can be visited for free (as is the case with many cultural spots in the UK).

As we know, artists may take inspiration for their works from the past. In 2007 a well-known, Italian, contemporary artist, Maurizio Cattelan, created a unique installation in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. All as he named it, was a retrospective exhibition in which Cattelan’s entire oeuvre was suspended from the oculus of the museum’s iconic rotunda. A large collection of curiosities, artificially made objects, or natural objects with no connection between them reminds one of an updated version of a Wunderkammer. Starting at the entrance, the first installation which appeared to the visitor was the Novecento (1997), a stuffed horse hanging from the ceiling.

Cattelan’s inspiration for this work was certainly the Hanging Embalmed Crocodile from the sanctuary of Our Lady of the Graces in the Italian city Mantova. The real crocodile (not a model) was added to the church in the 15th or 16th century and has recently been restored.

There are various legends surrounding the origin and the meaning of the crocodile’s collocation, possibly as an ex voto. However, the most convincing theory is that in antiquity the figures of dragons, crocodiles, or snakes were seen with promiscuity and often, in the Christian era, they were associated with evil as a personification of devils or animals that lead to sin. The placement of these animals in churches, therefore, has a strong symbolic meaning because chaining the animal at the top in the vault of the church means blocking the evil and at the same time exposing a concrete warning for the faithful against human predisposition to error.

Another type of the cabinet of curiosities created with contemporary artistic techniques could be found in assemblage or collage. For the assemblage, we can observe an interesting example in Marcel Duchamp’s BoÎte-en-valise, Wendy Aikin’s cabinets of curiosities, or Joseph Cornell’s parrot boxes like the one in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

If you are an art lover and you enjoy quality cinematography, you should add to your movie list a psychological-thriller directed by Giuseppe Tornatore: The Best Offer (2013). In multiple scenes of the movie feature a room full of portraits displayed all over the walls. It is an incredibly fascinating and breathtaking sight, similar to David Teniers’ painting below. It is a collection which the protagonist of the movie, director of a preeminent auction house Virgil Oldman (Geoffrey Rush), amassed throughout his entire life. As we may notice, Oldman only collects female portraits. The reason for this, along with the plot peripeteia I leave to your own curiosity. So, go watch it!

As we can see, collecting precious objects has been a long-standing tradition among the powerful. Therefore early cabinets of curiosities and Wunderkammers functioned as social status symbols. All these paintings and works of art remind us of how important the role of collecting was in the history of western civilization. They also show us how personal collections laid the foundations of the most well-known museums and galleries of today.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!