Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

Carnival is the festive season that comes before the Lent in Western Christian tradition. It is celebrated in many various ways across the world. To celebrate this amazing period in the year join us for the five takes on carnival in art.

People come together during the carnival to celebrate before the season of austerity. It is also a reversal ritual, in which social roles are reversed and norms about desired behavior are suspended. The name derives from the Latin phrase carnem levare, which means to take away or remove the meat/flesh. Some of the best-known carnivals include the one in Rio de Janeiro, and in Venice, but we also have a carnival in Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Mardi Gras in New Orleans. There is an amazing carnival in Trinidad and Tobago that started as a rebellion against slavery but has transformed into one of the biggest street parties in the Caribbean.

The first of the five takes on carnival in art is The Harlequin’s Carnival by Joan Miró. This is one of Miró’s most famous paintings. It is also one of his first Surrealist ones after the group coalesced around André Breton in 1924. The painting pulsates with the joy of life, there is movement, music, and fun. And yet the Harlequin looks desolate (if you struggle to find him, he is the elongated guitar with a red/blue round head). Some attribute this to the hole in his stomach, alluding to the fact that at that time Miró often struggled financially and went hungry. This however does not distract everyone else from having fun. Just looking at the painting you want to sway to the music.

Harlequin’s character originates from the Italian commedia dell’arte. He is easily recognizable by his chequered costume. Typically he is a light-hearted and witty character, getting in the way of his master’s plans and madly in love with Columbina, for whose graces he often competes for with the more serious and melancholic Pierrot.

Let’s move continents and also change the understanding of the carnival a bit. Winslow Homer painted this work in the final year of the Reconstruction when the federal troops withdrew from the South. We see the group here preparing for a Christmas-time festivity known in the South as Jonkonnu. The celebration originates from the culture of the British West Indies, the festival blended African and English traditions. Later it merged with the July 4th celebrations (hence the Stars and Stripes that one of the kids is holding). Here we see two women dressing the Lord of Misrule, a very Harlequin-like figure. Both are focused on sewing him into his costume, the children watch with awe.

The painting is far from the liberated joy of Miró’s carnival. Instead, there is silence and focus, a sense of an important celebration coming up. But also poverty and the feeling that the hopes of emancipation are still far from the realities of black life in the South.

At first sight, we are back to having fun. Francisco Goya gives us a group of wildly dancing women and men. But there is something sinister about the banner they are carrying. The King of the Carnival smiles, but it is a sinister smile, nothing good can come out of it. Also the closer we look at the background the more the masked faces remind us of eyeless skulls. The man dressed as a devil looks ready to catch and kidnap the joyful and careless woman on the left. Even if you look at the distribution of light we have the light circle in the middle, including the three central dancing figures dressed in white, but it is surrounded by a lot darker clothes of the other revelers. And the King of the Carnival menacingly floats above them.

The Burial of the Sardine (Entierro de la sardina) is a Spanish ceremony at the end of the carnival. It consists of a parade, mockingly pretending to be a funeral procession and the burning of a figure of the sardine. Through this ritual society is reborn, transformed, and renewed.

Here I’ll admit my ignorance, I always thought that Pulcinella was a woman! Now I stand corrected. It is another character from commedia dell’arte, but a lot less appealing than Harlequin. For those of you more into the British culture, he is the original Mr. Punch. Pulcinella was raised by two fathers Maccus, loud, sarcastic, rude, and cruel, and Bucco, a scheming and intelligent but nervous thief. He takes after both of them and this also is reflected in his disjointed physique. Pulcinella is fat and hunchbacked, with a large nose.

There is not much that is appealing in Pulcinella, he plays dumb when he is fully aware of the situation, only to pretend to be the most intelligent when being completely ignorant. His only goal is to rise above his station, but without working for it. Pulcinella is the ultimate self-preservationist, looking out for himself in almost every situation, yet he still manages to sort out the affairs of everyone around him. He goes out of his way to avoid responsibility, yet always ends up with more of it than he bargained for.

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo was a son of the somewhat more accomplished Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Pulcinella was certainly fascinating to him and one of his inspirations. He created over 100 drawings of the character in a series called Entertainment for Children. This painting is also part of a series of four. The Triumph of Pulcinella pokes fun at triumphal entries familiar from traditional ceremonies where the triumphant is the center of attention.

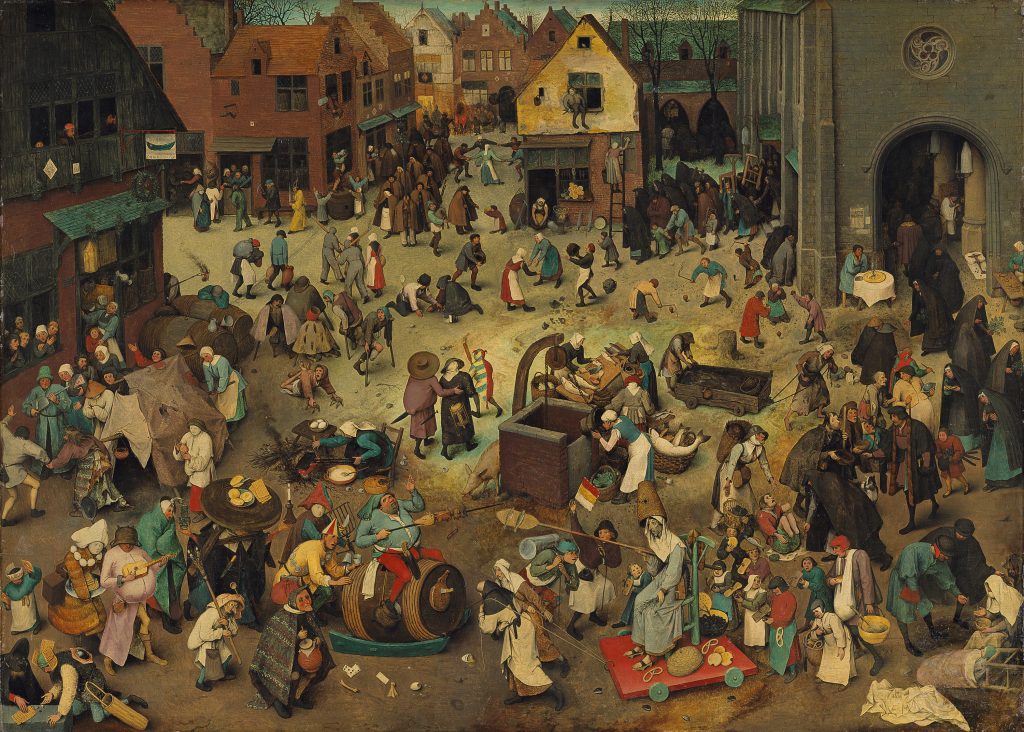

It is a classic and we could not miss it from this list. The left-hand side shows the carnival, we have an inn here, livestock, opulent loaves of bread. There are people drinking beer and we can even find a sleeping drunk. No one pays any attention to the group of crippled beggars. In contrast on the right-hand side, we have the church, fish, pretzels, and modest flatbreads. People willingly give alms to the poor and sick.

In the center of the painting, we can see a couple with their backs turned to us. They follow a man dressed like a jester carrying a torch. The man looks like he has a sack on his back under his cloak, which can be associated with the representation of egotism. The woman has an extinguished lantern attached to her belt, alluding to her ignorance. They both follow the fool with a torch, and we know nothing good can come out of it.

Front and center of the painting we have, of course, the title fight. Carnival is a butcher sitting on a barrel, while Lent is a nun wielding fish. While we know that the excesses of carnival cannot go on forever I must admit that Lent does not look very appealing to me either. Happy carnival! Let’s enjoy it while it lasts!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!