Skiing in Art History

Artists have long captured the magic of snow. During the 19th century, when winter sports like skiing, skating, and sledding became more popular in...

Louisa Mahoney 5 February 2025

20 January 2025 min Read

Carousels, roundabouts, and merry-go-rounds have a long history documented in art, stemming back to the time of the Crusades. They were used as a method of training for combat, with riders galloping in circles and throwing balls at one another. Eventually, these became more of a competition using their swords, which the Italian crusaders called carosello or ‘little war’. This was taken up in France, where the word ‘carousel’ originated.

A practice device was invented with wooden horses suspended on arms that were rotated by hand or by horses, with the soldiers mounted on the horses. This looked like fun to the casual observer, and it was from these small beginnings that the entertainment of sitting on a carved animal while riding around the central point really took off.

This canvas by the French mannerist, glass maker, and illustrator, Antoine Caron, depicts what appears to be a display of military skills. The riders circle around and throw their spears. The audience to the left is clearly of the upper classes going by their clothes. The inclusion of such an exotic creature as the elephant reveals how much this was now seen as entertainment rather than as a method to train soldiers for battle.

Artists have frequently depicted this device and they way in which it has become an integral part of our entertainment landscape.

The popularity of the funfair and, in particular, the carousels, took off in the 19th century all over Europe. In this ceramic painting, the Hungarian artist József Rippl-Rónai has his rider galloping along in the race with the other horses. Her waist ribbons fly in the wind and, although the rider is faceless, her body language tells you that she is enjoying the freedom, ironic as it is that the horses are never going to escape their life on the carousel.

Lovis Corinth, a German artist, has taken an impressionist viewpoint of the scene. The action is cropped so that we can see the children looking back into the crowd from their positions on the carousel. The spectators look on the “romance” side of the horses; the painted side, individualizing the steeds, allowing the children to imagine what it would be like to ride away on their very own horse.

The French love a good time and nowhere could people enjoy themselves more than in the squares of Paris. Here, Devambez takes a bird’s eye view of a scene in the Place Pigalle, a popular entertainment spot then and now. The cool beauty of Sacre Coeur watches over the masses of people in their brightly colored clothes, as they move across the square, taking in all the fun of the fair. A place to see and be seen.

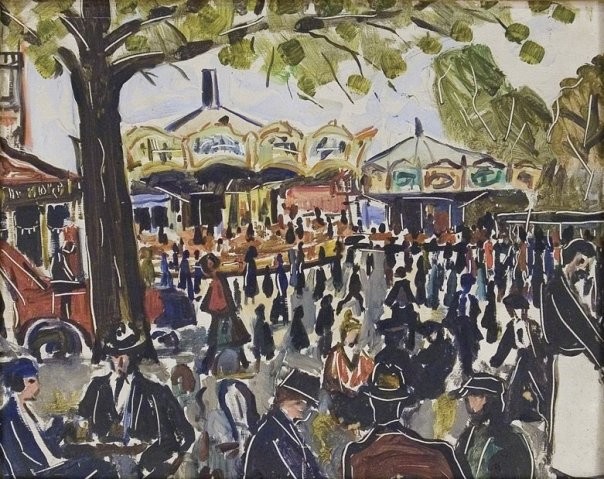

The Georgian expressionist, Shalva Kikodze, was also taken with the way the Parisians treated the fun fair as a place to meet and be entertained after he moved to Paris in 1920. This scene takes us deep into the crowds and we see the patrons of the cafes on the outside; the waiter in his white apron attends to his tables. The multiple carousels dominate the background with their colorful designs, contrasting with the dark clothing of the Parisians below.

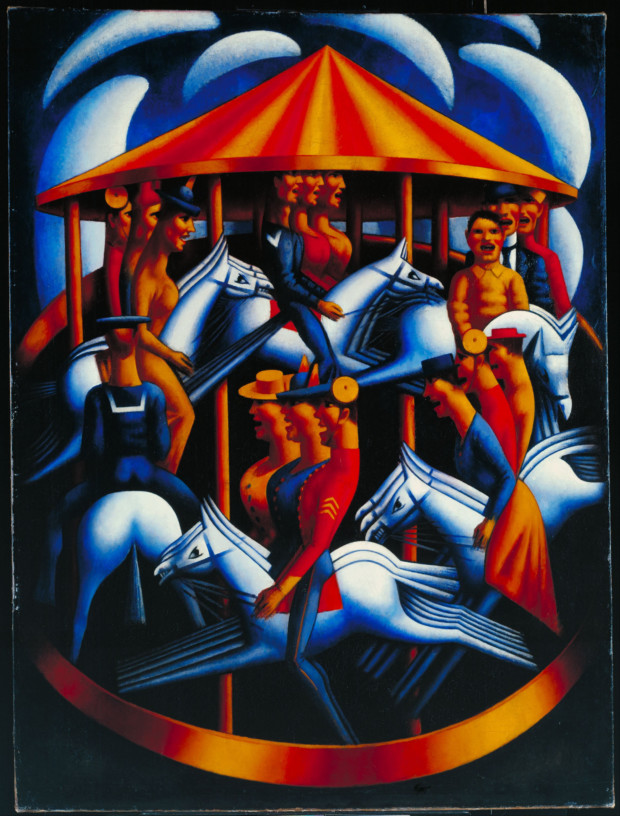

The first thing to strike you in Gertler’s canvas is the uniforms. You can imagine a Sunday afternoon on the local green; soldiers and sailors are out with their sweethearts for a carefree stroll before they depart to fight for their King and Country. To allow the closeness that society would not allow, the couples would ride side by side. But then you see their expressions. These are not faces that exude happiness and joy – the feelings that this ride would usually instill. These faces are fixed in a scream; the ride is in perpetual motion: there is no escape from what is to come. The use of primary colors gives a childish perspective to this scene which adds to the horror.

Gertler was a conscientious objector and he initially had problems in showing this. When it eventually was shown, it was regarded by many critics as the most important war painting. D. H. Lawrence wrote to Gertler:

“I have just seen your terrible and dreadful picture Merry-go-round. This is the first picture you have painted: it is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great and true. But it is horrible and terrifying. If they tell you it is obscene, they will say truly. You have made a real and ultimate revelation. I think this picture is your arrival.”

At the time that Stanley Spencer worked on this, he was separated from his second wife and was living alone. The sense of melancholy that this scene on Hampstead Heath creates is palpable. The lack of people and the lofty view all point to a man whose loneliness has emptied the world of all meaning. The never-ending rotation of the roundabout would only magnify the feelings of hopelessness. However, with this style of roundabout, the chairs are suspended by chains. It was only recently invented and throws the rider out from the center of the vortex, giving a small sense of the freedom that could come about, if one was only ready to take that first step.

This linocut print is dizzying in every aspect and is an excellent comparison to Gertler’s work. While Gertler has frozen his “victims” in time and space, never to leave, Power has his figures flying through the air at a frenetic pace, creating a dazzling kaleidoscope of movement. When you look at Spencer’s static ride, you can now see what excitement can come from this. At first, you can experience the thrill of the ride, but you very quickly realize that the riders are at the very edge of their seats and the danger becomes all too apparent. The use of just two colors, Chinese and chrome orange and Chinese blue, along with the curves, creates density. The lighter shades at the outer edges form the force lines and it is this that evokes the fearful nature of this ride.

A ride that goes nowhere, on static animals that will never leave their stations does not sound that appealing, however, the timeless nature of carousels in art means that it will always have a place in any environment designed for fun and imagination

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!