Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

American painter Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) cannot be neatly pigeonholed into any artistic category. Rather, she sits at a curious intersection between Realism and Impressionism. Successfully forging her way in a male-dominated art world, Beaux became a premiere portraitist of the East Coast elite. Today, she is known for her ability to capture the essence of her sitters, among them Edith Roosevelt, Admiral Sir David Beatty, and Georges Clemenceau. Here we take a closer look at the society portraitist by delving into ten of her most remarkable paintings.

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Eliza Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) began her career as a commercial artist, making technical drawings of fossils for a U.S. Geological Survey project. In 1888, like many other aspiring 19th-century artists, she moved to Paris where she spent two years studying at the Académie Julian. She was the first woman faculty member at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where she taught portrait painting and drawing for twenty years. Focusing on her career with a “will of iron,”1 Beaux would become one of the leading society portraitists of her day.

Miss Beaux is not only the greatest living woman painter, but the best that has ever lived.

Cecilia Beaux, The Last Days of Infancy, 1883-1885, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Museum’s website.

This tender painting, The Last Days of Infancy, launched Beaux’s career. Beaux, who never married and remained childless, was a doting aunt. Here we see an intimate portrait of the artist’s sister and nephew, whom she would paint repeatedly. The work received widespread praise and was even entered into the Paris Salon of 1887, a professional turning point for the artist. The painting is rooted in Beaux’s Academy training, meticulously rendered with its darkened palette, technical precision, and realism.

Cecilia Beaux, A Little Girl, 1887, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Museum’s website.

Beaux’s early life was marked by her mother’s death, passing away just days after her birth. After her father abandoned Beaux and her sister to move to France, the girls were entrusted to Beaux’s maternal grandmother and aunts who steadfastly supported Beaux’s career in the arts. Raised in a world of strong women, Beaux acquired her committed work ethic and love of art. Here, a young girl sits quietly as she gazes intently into the viewer’s eyes. Sitting atop her lap are several wilting flowers, complementing her sullen gaze. Children would be a recurring theme throughout Beaux’s oeuvre.

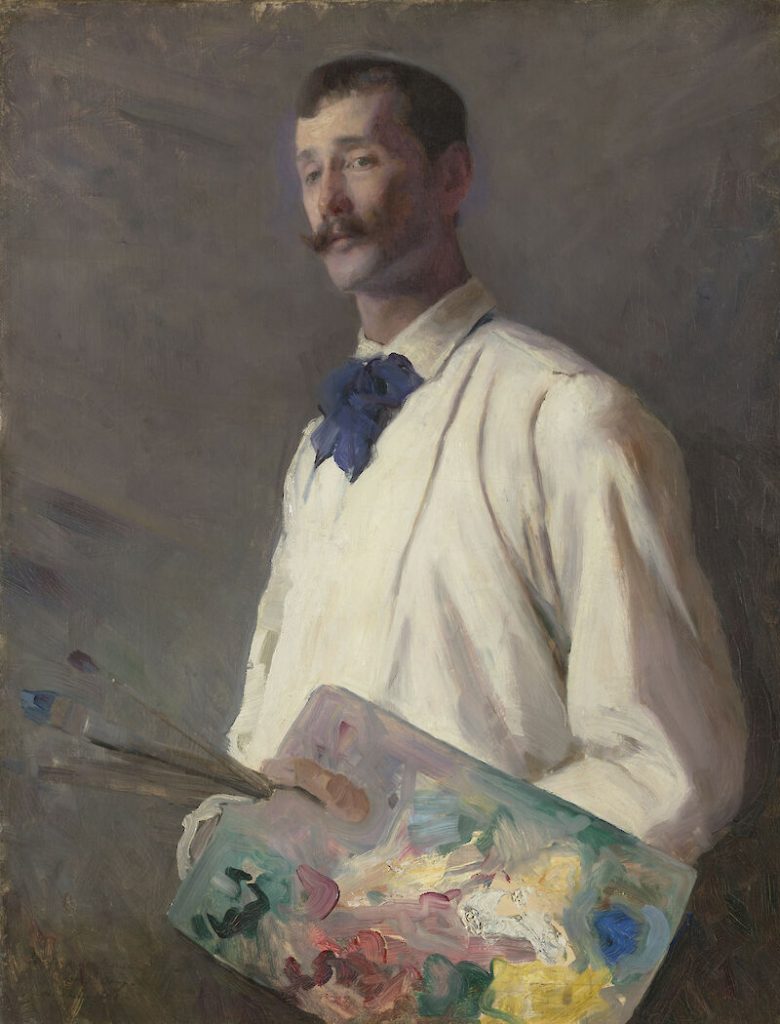

Cecilia Beaux, Alexander Harrison, 1888, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, USA. Obelisk Art History.

Looking to advance her career, Beaux traveled to Paris, where she enrolled in the Académie Julian, an alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. With a new spring in her step, she painted this buoyant portrait of fellow Philadelphian artist Alexander Harrison. From behind his paint-laden palette, he casts a defiant yet playful gaze. This is an early example of Beaux’s ability to breathe life into her sitters.

Cecilia Beaux, Twilight Confidences, 1888, Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA, USA. Museum’s website.

When the Académie Julian closed its doors for the summer, Beaux traveled to the seaside town of Concorneau. Captivated by Breton peasants and their crisp collars and caps, she found in them the perfect sitters for a different sort of portrait. This arresting image represents the artist’s first major attempt at en plein air painting. Using a brightened color palette, Beaux experiments with the effects of light while also managing to perfectly capture the serene austerity of her subjects.

Cecilia Beaux, Dorothea and Francesca, 1898, Art Insitute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Museum’s website.

Here we see two sisters from the influential New York Gilder family. The Gilders considered Beaux a close friend, supporting her art and introducing her to numerous prominent members of society, including Theodore Roosevelt. Beaux painted this double portrait in the tobacco barn on the property of the Gilders’ summer residence in Tyringham, Massachusetts. (The artist reportedly wore rubber boots while working due to the incessant New England autumn rain). The young sisters perform a playful dance they’ve just invented, their side-by-side placement alluding to the transition from girlhood to womanhood.

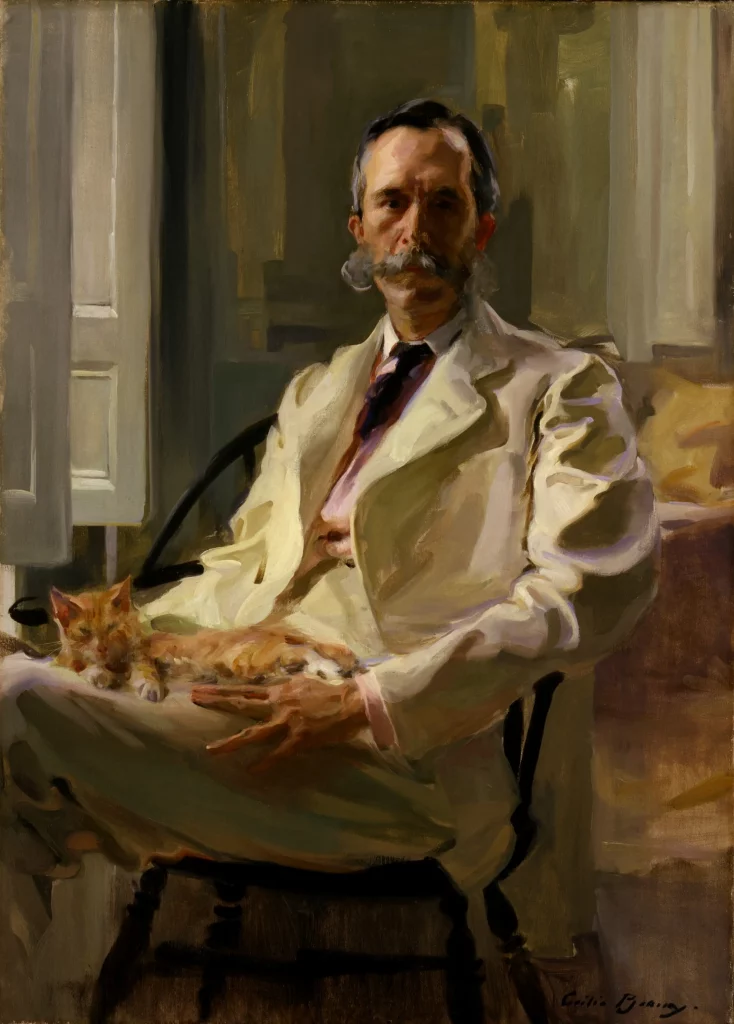

Cecilia Beaux, Man with the Cat (Henry Sturgis Drinker), 1898, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.

This is an intimate portrait of the artist’s brother-in-law, a railroad executive, set in a domestic space. Sporting a mutton-chop beard and crisp linen suit, Drinker exudes a commanding presence. An accomplished lawyer and engineer, he would later become president of Lehigh University. Man with Cat embodies Beaux’s expressive portraiture, in which she explores the complexities of one’s identity. Her exquisite brushwork and interplay of light and shadow further heighten the picture’s allure.

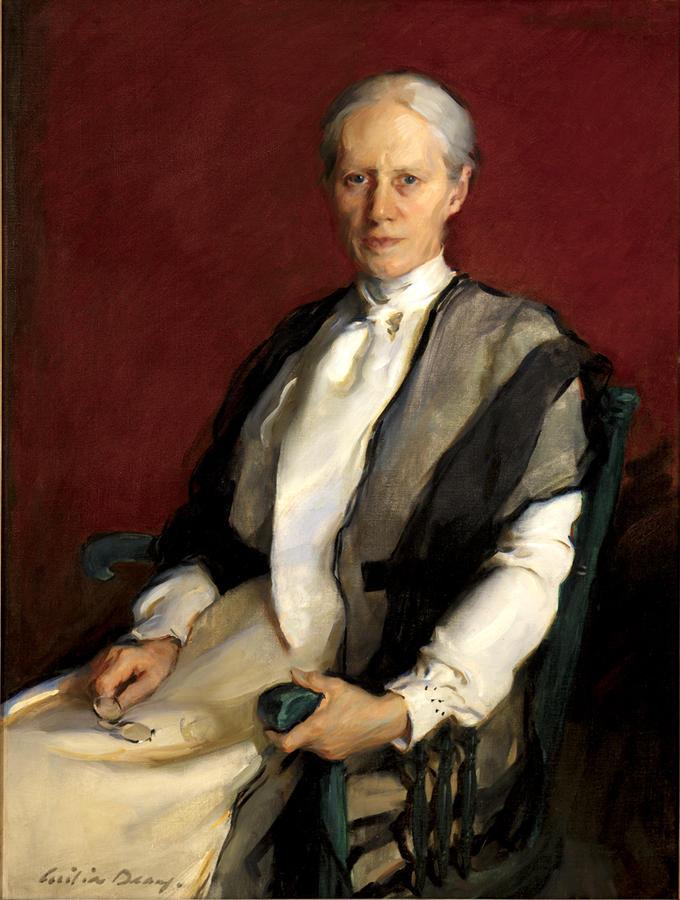

Cecilia Beaux, Portrait of Sarah E. Doyle, ca. 1902, Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, RI, USA. Museum’s website.

Following her move to New York in 1900, Beaux received a series of important commissions, many from professional women, including suffragettes, socialites, and presidents of women’s colleges. Here we see Sarah Doyle, founder of Pembroke College at Brown University. Doyle’s former students commissioned the portrait to commemorate her profound influence on the women of their community. She wears academic robes and clutches her eyeglasses with her right hand. Set against a rich crimson backdrop, the portrait reflects Doyle’s quiet dignity and intellect.

Cecilia Beaux, Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt and Daughter Ethel, 1902, private collection. Wikipedia.

Perhaps Beaux’s most important commission of all was a portrait of the wife of then president of the United States Mr. Theodore Roosevelt, Edith, and her daughter, Ethel. Since President Roosevelt’s illness complicated the numerous sittings required, the sister of the Senator, Miss Bessie Kean, made frequent visits to the White House to pose in the First Lady’s gown for the portrait. Three decades later, in 1933, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt awarded Beaux the Chi Omega fraternity’s gold medal, calling her, “The American woman who had made the greatest contribution to the culture of the world.”2

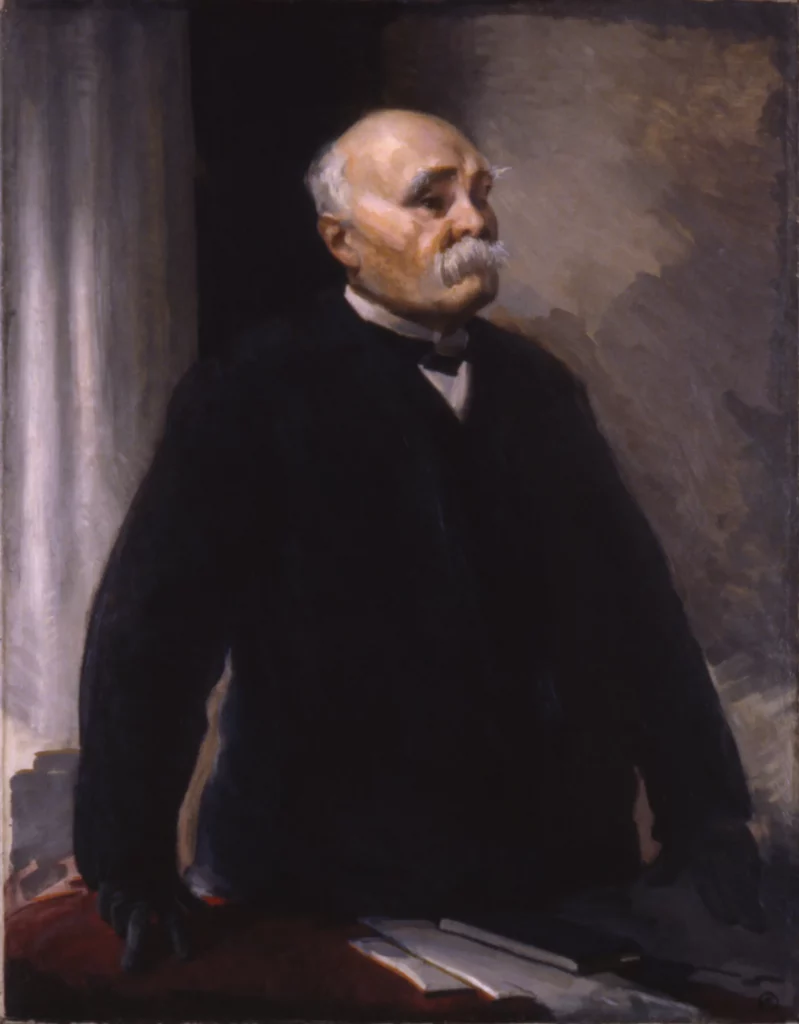

Cecilia Beaux, Georges Clemenceau, 1920, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.

After World War I, Beaux was one of the painters selected by the United States War Portraits Commission to execute commemorative portraits of war heroes, including Cardinal Mercier, Admiral Beatty, and this painting of Premier Georges Clemenceau. Clemenceau, the premier of France, signed the World War I peace treaty in 1919 at Versailles. Due to the statesman’s distaste for having his portrait painted, Beaux was only able to secure one sitting, finishing the painting from a single oil sketch.

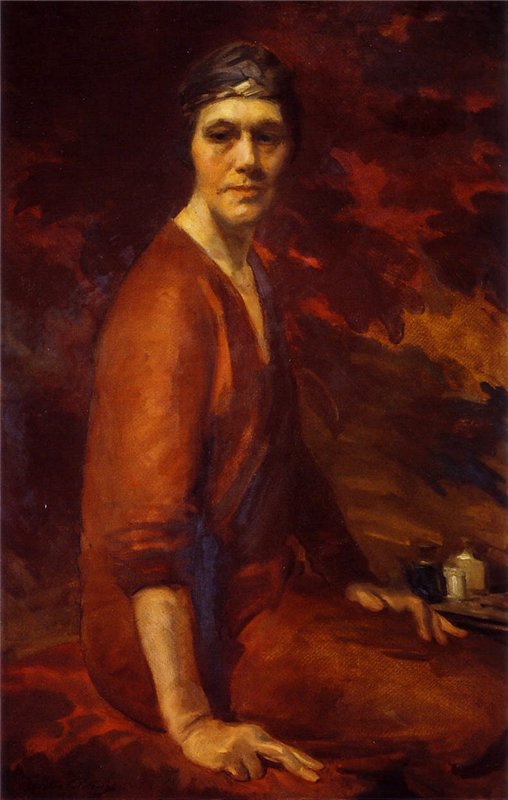

Cecilia Beaux, Self-Portrait, 1925, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Following an injury in 1924, Beaux’s artistic output waned significantly. However, that same year, she was invited by the Uffizi Gallery to contribute a self-portrait for the Medici collection. Here we see a pensive Beaux, eyes downcast, perhaps reflecting on her extensive and fertile career. The painting’s muted color palette brings an echo of her earlier work. She died in 1942 at the age of 87. Her achievements were largely forgotten until nearly 40 years after her death when interest in her career was revived by the women’s liberation movement.

Sarah Burns, Under the Skin: Reconsidering Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 124, No. 3, Cecilia Beaux: Phildelphia Artist (Jul., 2000), University of Pennsylvania Press.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!