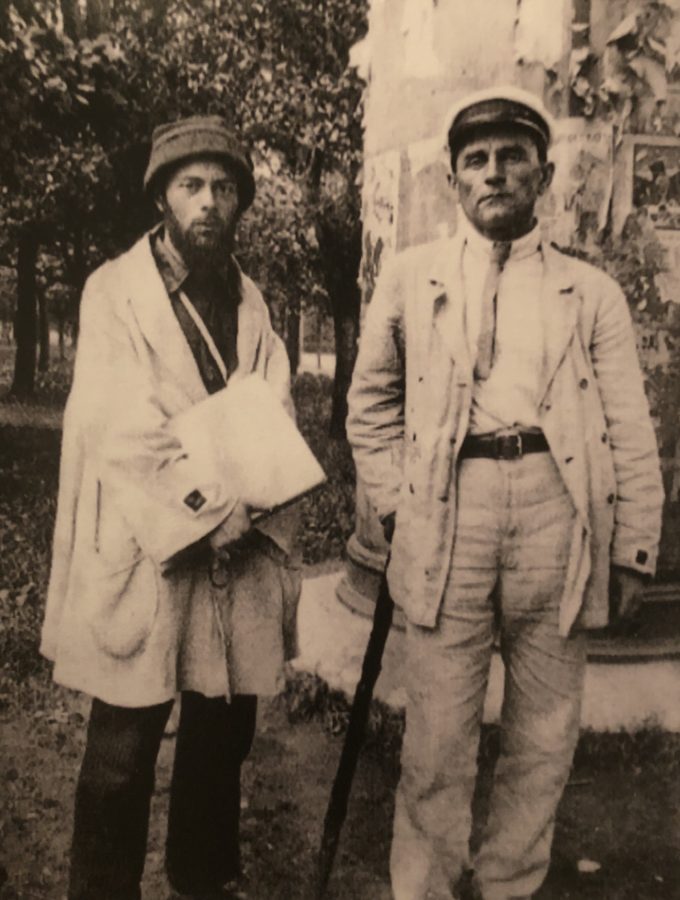

Marc Chagall and Kazimir Malevich have much in common. Both were artists. Both were deeply affected by the Russian Revolution.

Almost everything is over almost before it begins. We long for consistency, a foundation of belief, and a stabilizing influence. And once we have it, once we can smell it and taste it and feel it, we hope the feeling never goes away.

So it was with the Russian Revolution. Tsar Nicholas II had been forced to abdicate in March 1917. The provisional government that replaced him was overthrown in November 1917. And through this Bolshevik Revolution, the promise of a new Russia emerged.

This was the promise of change that took place in Russia in 1917. I do not wish to explore whether this change was for the best. I only wish to explore that both Chagall and Malevich believed this to be the case, and were motivated to be in the same place at the same time because of it.

This exhibition in New York City’s Jewish Museum, Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922, which will be on view until January 6, 2019, explores each man’s reaction to this life-altering event.

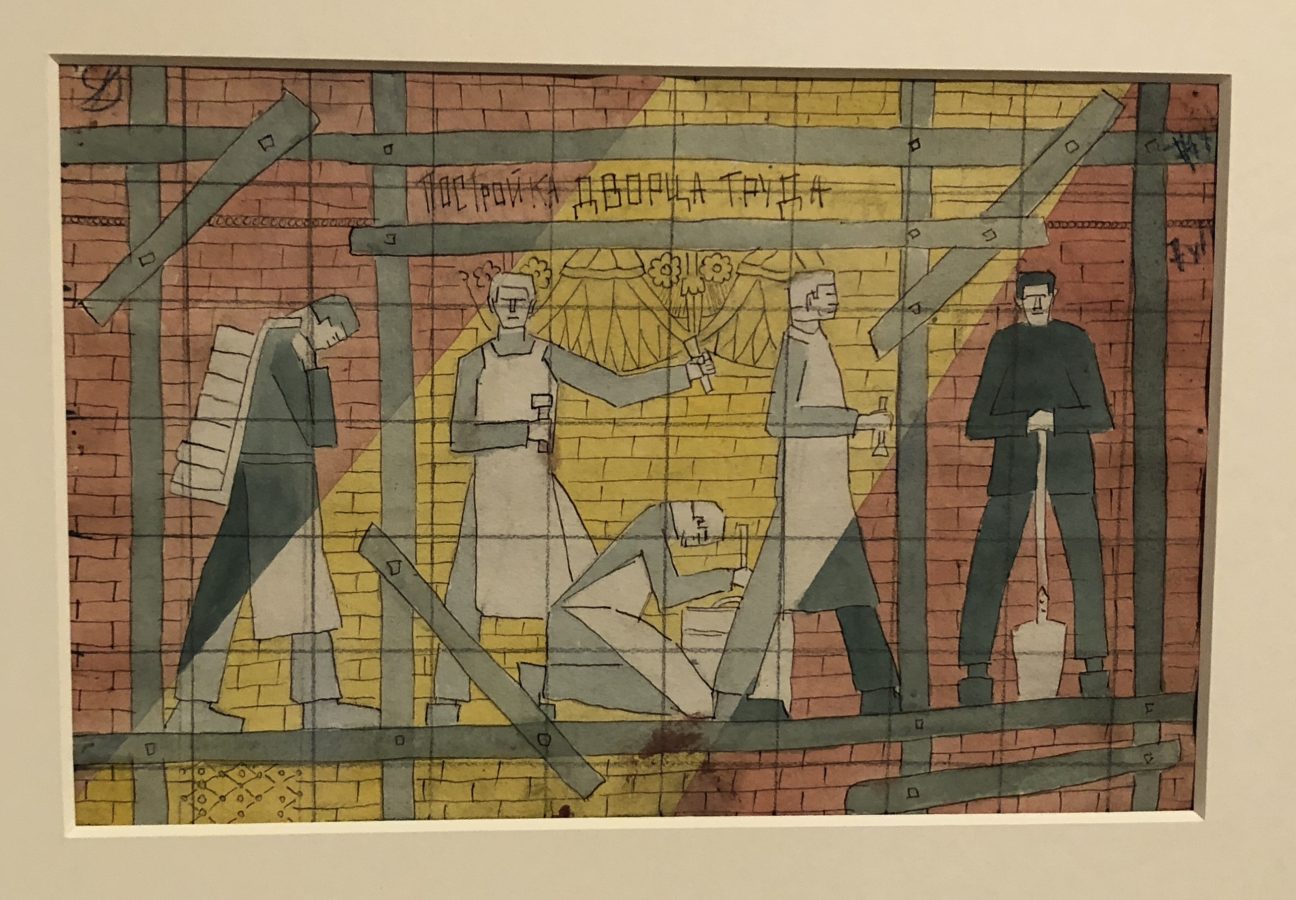

After the Russian October Revolution, Chagall was encouraged because a law was passed “abolishing all discrimination on the basis of religion or nationality.” Chagall “had the idea of establishing a revolutionary art school, open to all, without age restrictions or admission fees. The new government approved the project and Chagall was named Vitebsk’s Commissar of Arts in September 1918.”

Chagall was open to many artistic visions, both traditional and avant-garde. He asked his friend, El Lissitzky, to teach in his new school, The People’s Art School. El Lissitzky, in turn, was able to bring Kazimir Malevich in to teach as well.

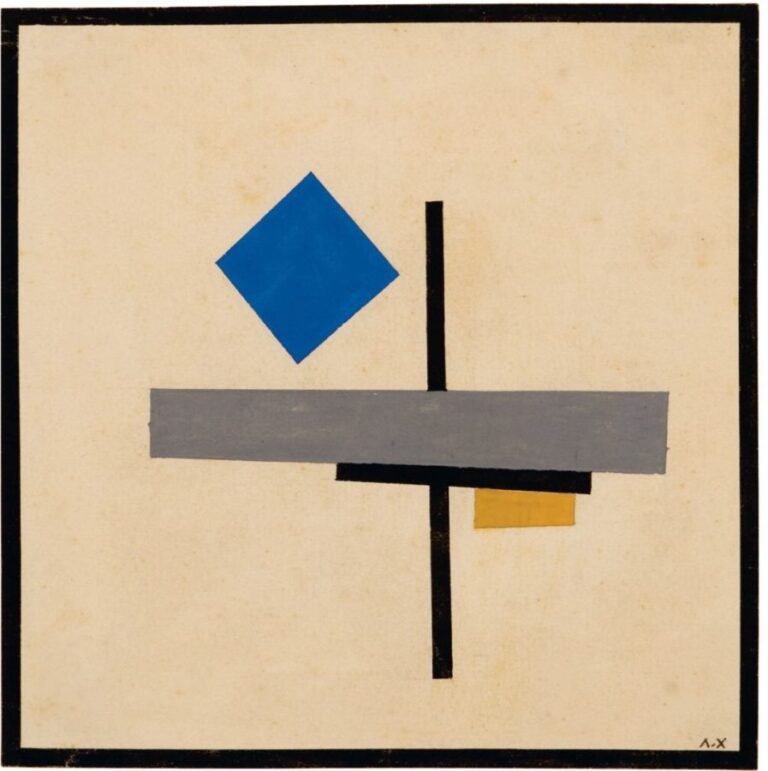

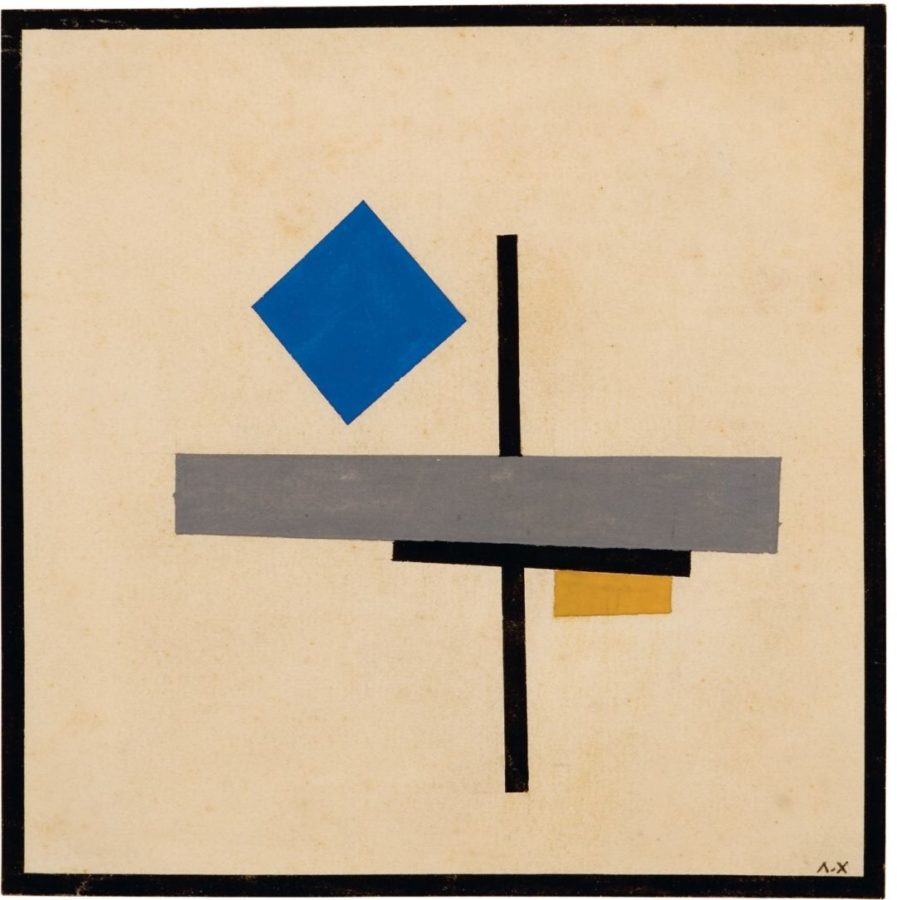

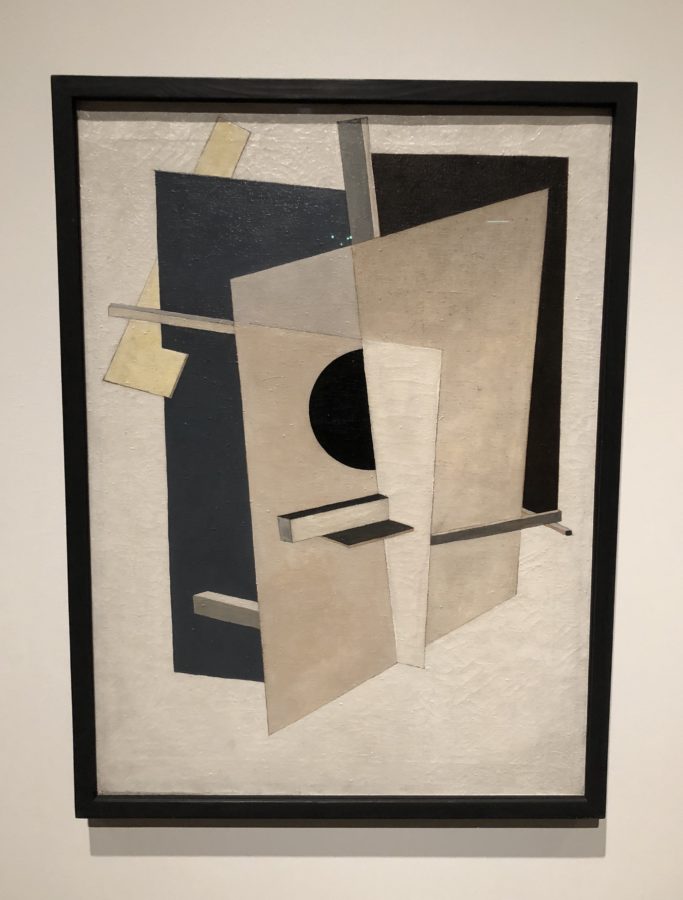

Malevich was the driving force behind Suprematism, which was his way of seeing the world. Malevich had founded a new art that would emerge and thrive in this ‘new world’ of post-tsarist Russia. The birthplace of this new ‘ism’ may have been the ‘0.10’ exhibition that took place in December 1915 in Moscow.

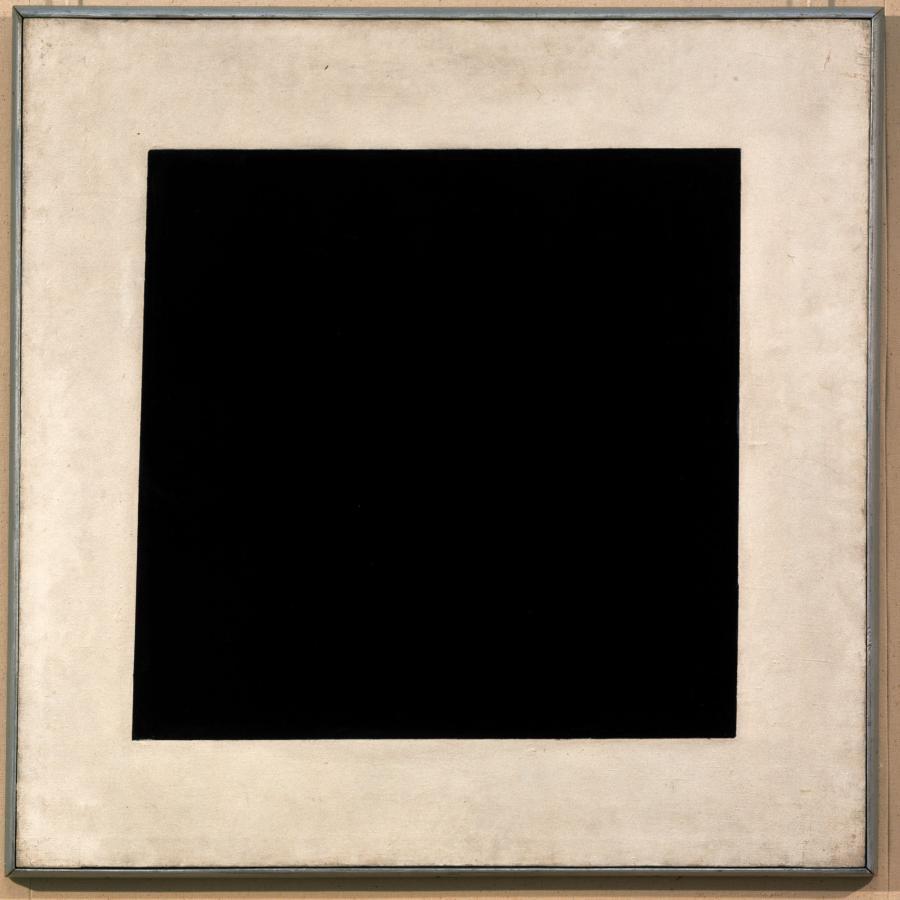

He wanted to paint pure abstraction, a non-figurative, non-objective reality, at least from a visual standpoint. So he would paint circles and squares and rectangles and lines. He painted a black square in 1915 that became one of the most significant paintings of the 20th century, and of the ‘0.10’ exhibition. He painted triangles as well. The range of colours was limited. The shape of his forms was also limited.

Even though these forms and colours bore no resemblance to the visual physical world, each object painted by the artist had symbolic meaning. The colour black represents death. The colour red represents blood. Or it can represent Russia. And on and on. The irony here is that even Malevich was not able to escape the reality of the physical world.

The ideas behind Suprematism are fascinating to me, especially when one considers these ideas in the context in which they were conceived. Suprematism (as well as the vision of the father of abstract art, Wassily Kandinsky) led to other visions of abstract art—the work of Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning, Piet Mondrian, Mark Rothko, and on and on—art that I love, art that moves me. None of this great art would have been made in the way that it was without Kazimir Malevich painting that black square.

Having said that, walking through the rooms of this exhibition took much less time than I had anticipated. Even though mysticism played a role in producing these paintings, I was not able to feel the deeper spiritual meaning that mysticism is supposed to bring. I enjoy looking at ‘imperfect’ shapes, both positive and negative. Imperfect shapes do not exist in Suprematism, for the most part. I enjoyed looking at some of the Suprematist paintings, both by Malevich and by others, but my attention span was short because I believe that most of what these paintings have to offer can be absorbed in a minute or less.

Malevich wrote a treatise on Suprematism called The Non-Objective World. The first sentence of the second essay, called Suprematism, reads:

Under Suprematism I understand the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art.

He also wrote:

The art of the past which stood, at least ostensibly, in the service of religion and the state, will take on new life in the pure (unapplied) art of Suprematism, which will build up a new world—the world of feeling…

Malevich believed that the general public was so distracted by how well the figurative forms in the paintings of Rubens, Rembrandt, etc. are modelled that it loses sight of the intense feeling that comes from them. Malevich’s solution was to remove objective reality, revealing the feeling that had been hidden before. The unfortunate result of this endeavour was to remove most of the feeling as well.

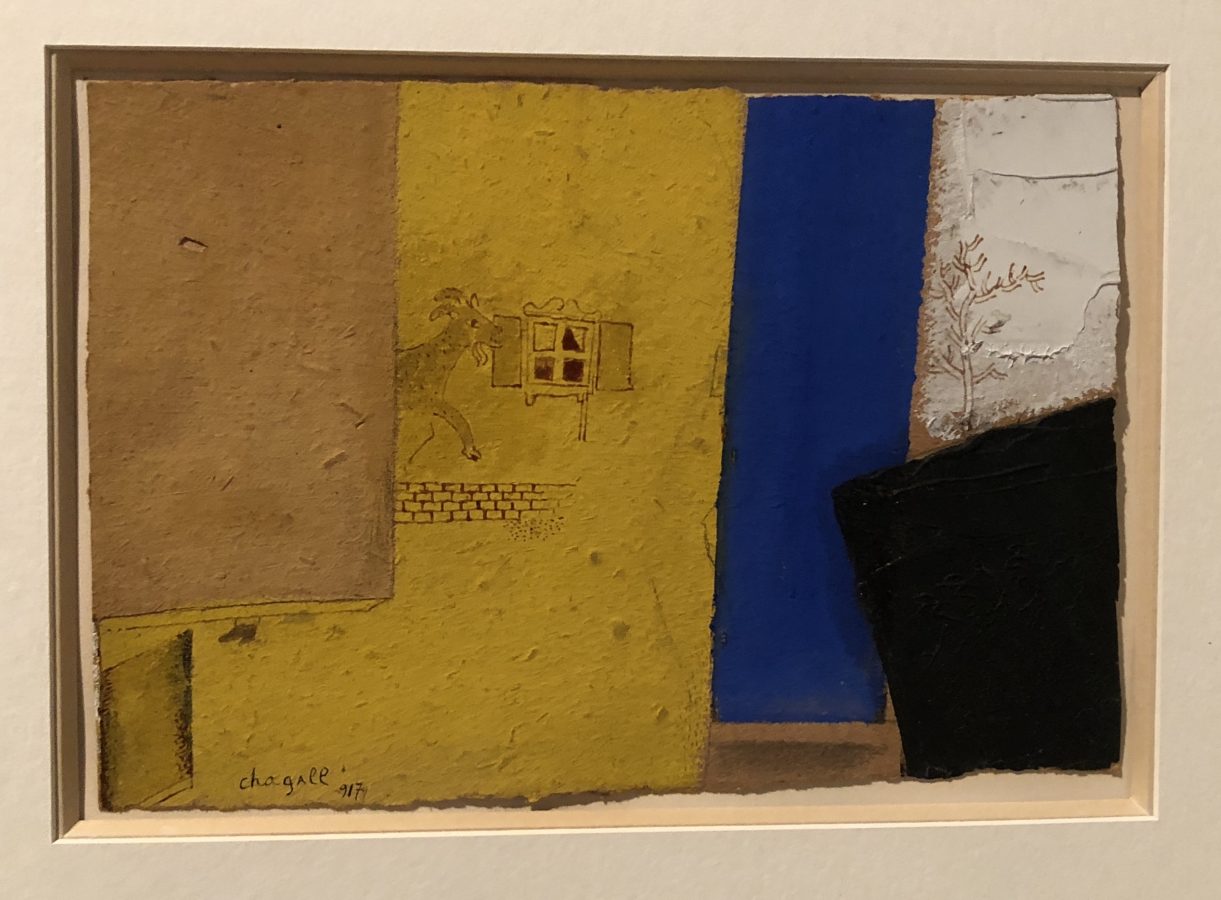

When I stand before the Chagall paintings, I am able to be with each of them for a much longer period of time than I was with the Suprematist art. The first painting of the exhibition, ‘Double Portrait with Wine Glass,’ has so much to say to me. Chagall is sharing his joy of being with his wife, Bella. He is sharing his joy about returning to Vitebsk, the land of his birth, after having lived in Paris for several years. One of the reasons Chagall returned to Vitebsk was to marry Bella Rosenfeld. Chagall incorporates aspects of Cubism in this painting. The viewer is at once looking down at the buildings in the background while looking up at the figures in the foreground. The composition of most of the painting, from front to back, is compressed. Chagall’s head becomes a fragment of the body, cut off and pushed to the right (from the viewer’s perspective). Bella appears to be floating while, at the same time, she appears to be grounded as well. And the shadows of the right arm of the artist’s jacket are simplified by being painted as simple triangles.

Malevich saw Cubism as a stepping-stone to Suprematism. The journey goes from Cubism to Futurism to Suprematism. The assumption is that each new movement is a growth step away from the movement it succeeded. In Malevich’s world, Cubism is merely a means to an end. Malevich wrote: “We have reached suprematism, abandoning futurism as a loophole through which those lagging behind will pass.”

Unfortunately, Malevich was not alone in holding this view. His classes in the People’s School of Art became more popular than Chagall’s. Chagall, during this period, paid the price for being open to different ways of being an artist. He must not have realized that other artists of influence, especially those with differing views, were not always as open-minded as he was.

The ideas behind Suprematism are fascinating, but the paintings that sprouted from these ideas are not. For example, one wall of the exhibition has a series of paintings by David Yakerson, another Suprematist artist. There are drawings of geometricized robots. He has other drawings that explore the relationship between a circle and a larger square. Apparently, this series of drawings is meant to be taken in as a unified whole, and when one does so, one can see movement as the black circle travels along the picture plane, at first outside the square, and then inside. I enjoy looking at these images, but the experience of seeing these objects for the fourth time is the same experience I had the first time. Art that has the most profound effect on me is art that has something new to offer each time I stand in front of it. I feel this way about people too.

As one may imagine, Chagall had a strong reaction to the role that Suprematism has played in his life. His painting, ‘Compositions with Circles and Goat (State Jewish Chamber Theater)’ from 1920, is an example of this. As the description in the Jewish Museum emphasizes, “Reminiscent of Lissitzky’s Had Gadya illustrations and Prouns, the overall scene gloriously taunts his former friend who had distanced himself from Chagall to follow Malevich.” The former friend is Lissitzky.

Suprematism had a relatively short shelf life. Joseph Stalin did not endorse this way of painting. Stalin referred to the avant-garde as having “bourgeois industrialist decadence.” Stalin assumed control over the Soviet Union after the death of Lenin in 1924. By 1928, Malevich had been forced to abandon Suprematism. By 1935, Malevich was gone as well, a victim of cancer. Chagall lived for another fifty years, which is another lifetime. And one may argue that the optimism from the Russian Revolution died relatively quickly as well.

This exhibition does a wonderful job of taking a slice of life from the years 1918-1922 and transporting us back to this time. I was able to experience the elation of Chagall at the beginning of this period, and was able to feel his disappointment in how it all turned out in the end. I saw this exhibition through the eyes of Chagall and highly recommend this thought-provoking exhibition.

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0486429741″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/41RQVM5B5BL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”122″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0500202079″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/51PX8DZ9AtL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”114″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”3836546396″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/51b4m8NMCmL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”132″]