5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Today I would like to talk about Charles Keeping, an illustrator whom I discovered in my childhood. You may already be familiar with his work, perhaps from your own childhood. Especially if you were ever a fan of poetry, ghost stories, or Greek myths! If not, I hope that you enjoy looking at his work and take something special from it as I have always done.

Charles Keeping was born in 1924 in London. He left school aged 14 and went on to study art by correspondence. Keeping worked for a book printer, a munitions company, and a gas company before joining the Royal Navy in 1942, at the age of 18. He stayed in the Navy for four years, after which he returned home. Keeping eventually managed to secure a grant so that he could attend Regent Street Polytechnic. There he specialized in illustration and lithography.

Working as a freelance illustrator, Keeping’s output initially consisted of cartoons and comic strips. He also did some work in advertising and in illustrating textbooks. However, by 1956 he had begun working through an agent and started to illustrate children’s books. In 1970, he worked on a retelling of the Greek myths by Leon Garfield and Edward Blishen entitled The God Beneath the Sea, which is where I discovered him.

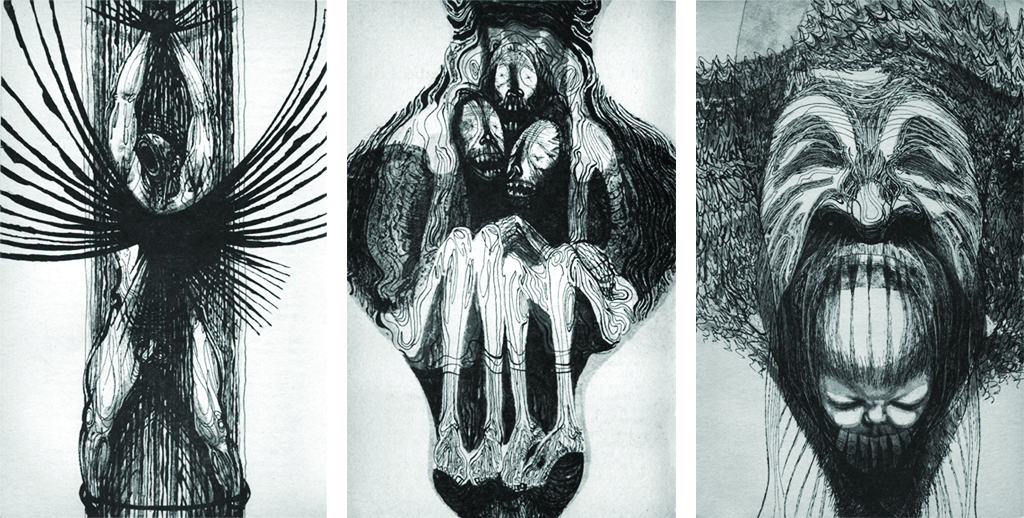

Imagine that you’re eleven years old, in a school library for the very first time, and you discover these:

I was astonished by these pictures, along with the others in the book. I borrowed them for more time than I should have just so that I could keep looking at them. Imagine my delight when I found another one in the same library, called The Golden Shadow. Again, I kept this book for weeks, reading every page, again and again, poring over the illustrations, utterly captivated.

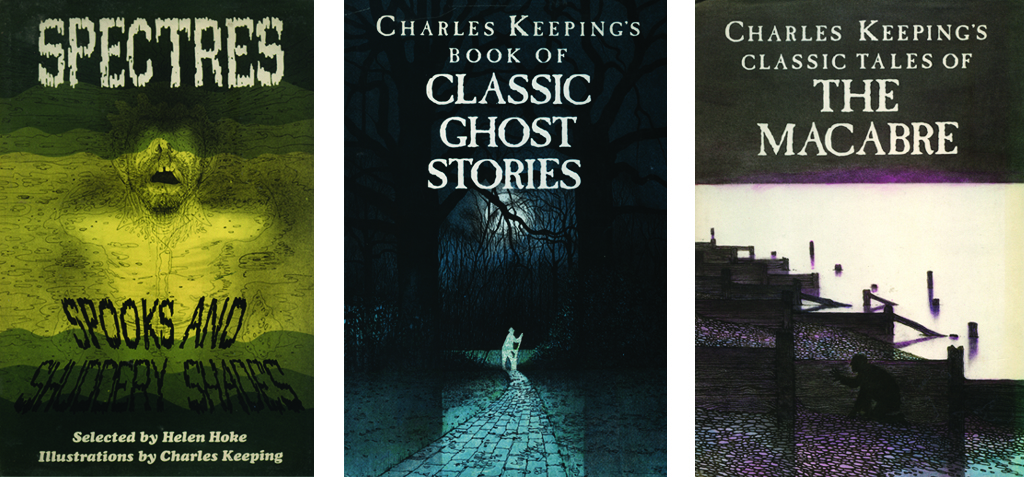

Then we moved away to a different part of England and for two or three years I forgot all about Keeping and his evocative, dark portrayals of the Greek Gods. One day, I found a book called Spectres, Spooks and Shuddery Shades in a bookshop. I was drawn to it by its subject matter of course because I am a big fan of ghost stories and Gothic fiction. I also immediately recognized the style of illustration on the front cover:

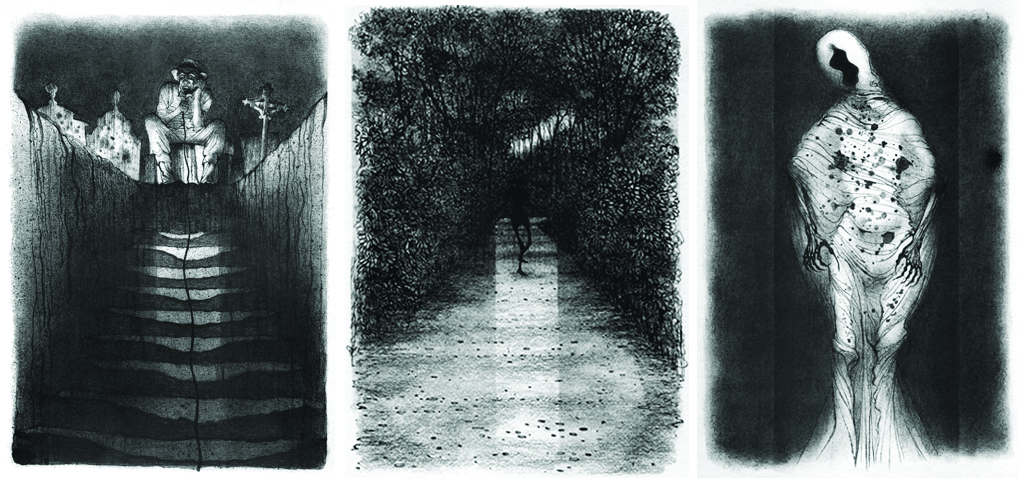

More books followed: I found a collection entitled Charles Keeping’s Book of Classic Ghost Stories, and then another called Charles Keeping’s Classic Tales of the Macabre. I still picture some of these drawings when I’m alone reading when there’s a storm and we have a power cut, or just when I’m walking up the stairs alone at night…

Keeping also produced artworks for Kevin Crossley-Holland’s retelling of Beowulf. Using his signature style of heavy black ink, graded shading, and clever use of lines to create sometimes densely packed and sometimes sparsely contoured. In his drawings, he brings to life not only characters who are young, old, monstrous, heroic, or sad, but also the cold, northern landscape in which Beowulf is set. We can really feel the hard, low winter sun whose warmth struggles to be felt through the fog, or the darkness of the rock against the dim, frozen skies of Denmark and Sweden.

Another poem that I think Keeping illustrated brilliantly (in 1981) is Alfred Noyes’ The Highwayman. This famous narrative poem of 1913 tells of a passionate love affair between the highwayman and Bess, the daughter of the landlord of a local inn. The tale is a tragic one and I won’t spoil it by telling you the whole plot, but please read it if you haven’t already because it is really lovely. Here is the opening to get you started!

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty tress,

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding –

Riding – riding –

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.Alfred Noyes, The Highwayman, 1913.

As you can imagine the illustrations are perfect and haunting. Keeping’s style coupled with his propensity for capturing the moment lends itself incomparably to the text, bringing it out of the imagination and onto the page. The moonlit night, Bess’ beauty, and the handsome highwayman are represented so well that we are entirely drawn into the world that Noyes has described with his words, and which Keeping then relates to us in artfully imagined pictures.

One of the qualities that make Keeping’s illustrations so compelling is their graphic realism. He does not try to hide or soften the realities of sexuality, jealousy, love, or violence which makes his drawings at times visceral and frightening rather than romanticized. Prometheus on the rock is bloody, Bess’ plight is morbidly real, Grendel’s appearance is monstrous, and Heracles’ anguish is shocking.

The tone of his art adheres to real-world experience, refusing to gloss over what are often brutal or desperate acts of vengeance, sacrifice, or murder. He treats his ghosts and otherworldly beings in the same way, endowing them with a similar honesty to his mythological characters. This is an aspect that sometimes brings them close enough to seem as though they might break out of our imaginations and spill into our lives.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!