Female Rage in Art

Since Auguste Toulmouche’s 1866 masterpiece The Reluctant Bride recently captured the internet’s attention, discussions about female rage...

Martha Teverson 6 May 2024

Chinese New Year or the Spring Festival celebrates the beginning of a new year based on the lunisolar calendar. In 2021, the first day of the Chinese New Year falls on February 12, the Year of the Ox. This festival lasts for fifteen days and includes different kinds of traditional celebrations. They go back to ancient times and became an art form. But can we start another tradition?

According to one of the traditions, the cycle of twelve animal signs derives from Chinese folklore as a method for naming the years. The animals follow one another in an established order: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig. Each animal has particular traits of character and people born in a certain year are believed to take on these characteristics.

If you are born in the Year of the Ox, you are likely to be strong, reliable, fair, and conscientious. You are also calm, patient, methodical, and can be trusted. Nevertheless, you can be stubborn at times and hate to fail. Although you do not lose your temper easily, you can become explosive and impulsive. On the brighter side, you have a great deal of common sense.

These characteristics might be a generalization and not all of them applicable to people born in the Year of the Ox. Nevertheless, Han Huang (723–787), a chancellor of the Tang dynasty (618–907), had some of these qualities in mind when he was creating his painting Five Oxen.

In his youth, Han Huang was firm and conscientious in his studies. He became an officer in the imperial guards and from there he received promotions until he got his coveted position. It may seem unusual that being a chancellor Han Huang was also a painter. However, at that time scholar-officials in China practiced the four arts. These activities included playing a musical instrument, the strategy game of Go, engaging in calligraphy, and painting.

Although Han Huang engaged in warfare, he could draw on the support of his extended family. He had at least five older and three younger brothers on whom he could count on in times of crisis.

Time passed and Han Huang’s Five Oxen became a national treasure. It is one of the most recognizable paintings in China. At the turn of the 20th century, the Eight-Nation Alliance attacked Beijing and took away Five Oxen. The national treasure was lost and only reemerged in the auction market in Hong Kong in 1950. At that time, Premier Zhou Enlai said that the painting must be bought for China at any cost. However, this task was not easy to achieve. Many overseas collectors came in great numbers, all trying to acquire the artwork. But what made Five Oxen so precious?

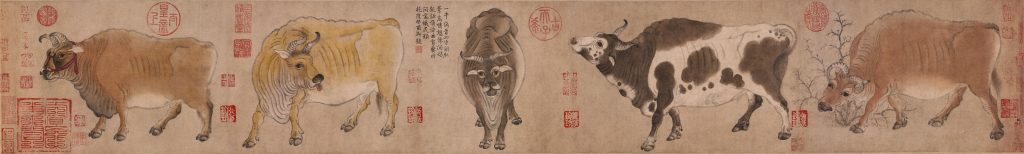

First, the composition of the painting is simple but bold. Han Huang drew the oxen in different shapes from right to left. They stand in line, appear happy or depressed. Looking around, the oxen form a unified whole. However, we can treat each image as an independent painting. Therefore, if Han Huang did not have strong artistic skills, he would probably depict all five animals directly.

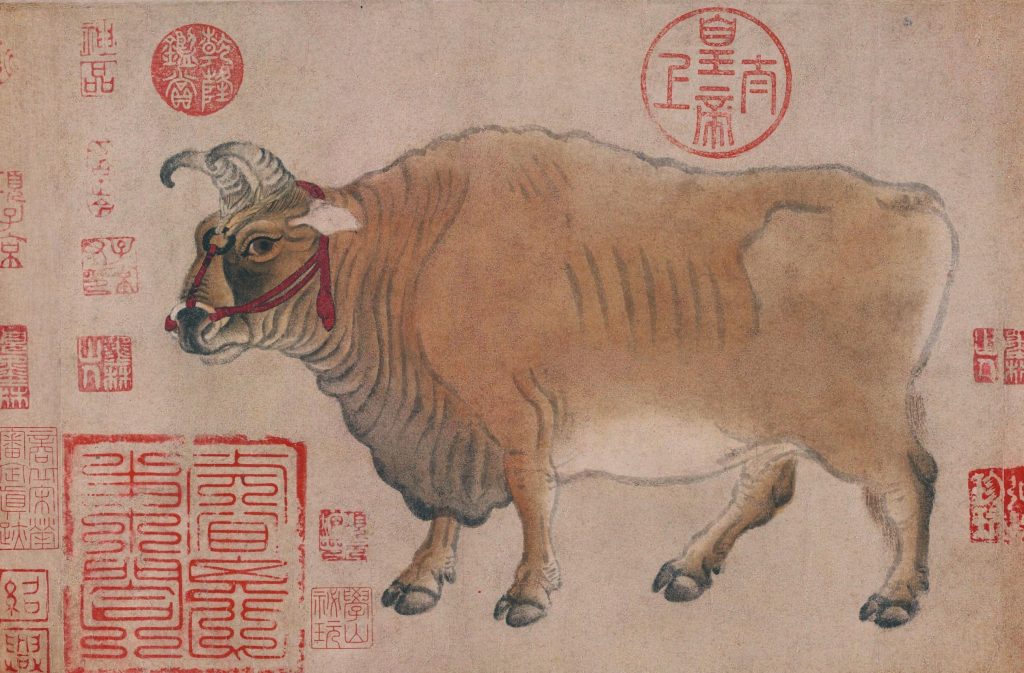

Furthermore, the artist captured each animal with accurate modeling and vivid shapes. With broad and vigorous brushstrokes, he defined the twists and joints of the bones tightly covered by the muscles. Each ox has a different posture: walking, standing, or bowing its head. Han Huang observed life carefully and deeply at that time. For example, many details, such as horns, eyes, and expressions show different characters of the oxen. He even drew their eyelashes very clearly.

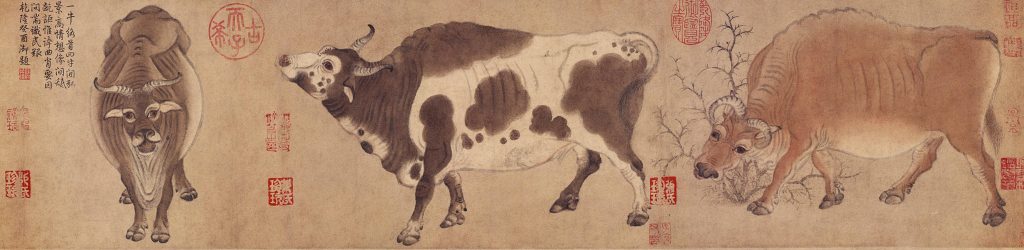

Here, we can see an old ox with a large body and horns in the shape of a crescent moon. This ox stretches out its neck and manages to scratch an itch. Therefore, it is comfortable and looks very pleased.

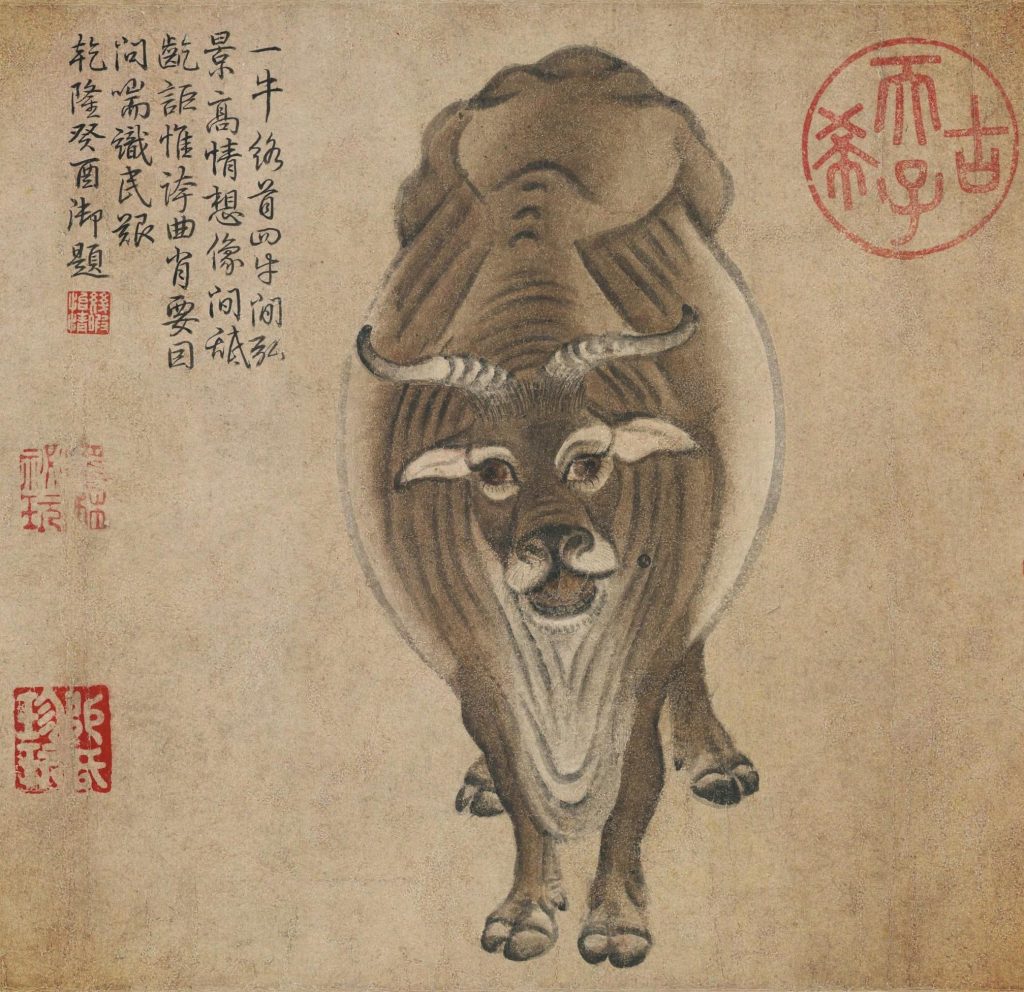

By contrast, the ox below stands still, looking discontent. It stares at those who appreciate the painting. It is different from the other four oxen. Its horns stretch forward. And it seems that it is ready to fight at any time. We notice that it is very stubborn and depressed.

Its head is tied to a rein. Among the five oxen, it is the only one that is tied. As a result, it is so angry. Might this be the reason why it looks so depressed? If so, this is understandable. It looks like it is about to say “Moo”.

Looking at the painting, we may wonder: why did Han Huang paint Five Oxen with different expressions? Was he interested in agriculture and animal husbandry and chose such a theme? Did Han Huang compare himself to the ox with a rein? By placing the ox with the bush in the same painting, he could imply that he preferred a retreat and a leisure life on the mountain. However, judging by his career and high position, Han Huang probably did not want to go into seclusion. Oxen shoulder heavy responsibilities and can be obedient. Therefore, by painting the ox with a rein, he could show his loyalty to the emperor.

Nevertheless, there is no certainty whether or not Five Oxen carried any moral, political, or religious implications. In the Tang dynasty (618–907), ox painting was traditionally considered an unsuitable theme for a gentleman’s study, likely because of the wild, unruly nature of the ox. On the contrary, horse painting was in vogue and enjoyed imperial patronage. We do not know, but could this ox tease a horse because of this inequality?

Despite the intense competition for the painting, China managed to keep it. We can see why many people valued Five Oxen. It showed that Tang dynasty painters achieved a high level of artistic skills. Although this painting may be a later copy with retouching, it gives us some idea of how Han Huang’s original looked like.

Ox-herding paintings did not become popular until the Song dynasty (960–1279). During this period artists and collectors valued the form-likeness in the ox painting. They believed that one of the artists who captured the form-likeness was Dai Song. As one of Han Huang’s students, he continued his teacher’s tradition of depicting cattle, especially oxen, bulls, and buffaloes. The rare works of this artist show us that he achieved great perfection in the chosen genre. Dai Song did try to take the bull by the horns when depicting oxen, but did he consider all of the details?

If he only thought that one day, a Song dynasty collector would take his collection of paintings and calligraphy to a courtyard. When a passing shepherd boy saw the painting Bullfighting by Dai Song, which the collector valued highly, he laughed. To the boy something was wrong. The cowherd revealed that when oxen are fighting, they exert strength by their horns. Because of the applied force, oxen’s tails are tautly drawn between their buttocks. However, Dai Song’s painting makes their tails stand up straight.

Perhaps, the collector could think of an old Chinese saying: “When farming, ask farmers; when weaving, ask weavers. This cannot be changed.” This means that we should observe things carefully and not imagine them. We should rely on objective facts, and we should ask for help if needed. Everyone has their own specialties.

Once favored in the Tang dynasty, horse painting declined in the subsequent period. Song scholar-officials started to relate themselves to the ordinary people, and accordingly, the ox. Artists created an ideal pastoral world, portraying the ease of rustic life with oxen returning home. In this idealized world, scholar-officials gained temporary relief from their busy, stressful careers in the big cities.

By painting a shepherd boy lying astride an ox, Li Tang (ca. 1049–1130) invoked the aura of rural tranquility. He depicted the ox and its calf, following close behind, to reveal the affection between a parent and the offspring. The artist applied pale washes to outline the bodies of the oxen. Then, he used the brush’s bristles to show the swirling patterns in the hair. Consequently, with these techniques, Li Tang captured the oxen in both spirit and form.

While viewing ox-herding paintings, scholar-officials found a way to express their ideal to fulfill the requirement of a virtuous Confucian official and retreat after the years of service. The emperor was also pleased by viewing such kinds of paintings because they implied his worthiness to rule and his political success. Thus, things took a new turn, and another era began.

Please help us to choose the Ox of the Year. Stubborn Moo relies on you. Let us know in the comments!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!