5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Traditional Chinese paintings are known for their distinctive style. When did Chinese painting begin and how to read it? What did it mean for the artists? Did they simply respond to and try to capture the world around them when they gazed into the distance? What was in their hearts when they developed their artistic style in constant reference to the past? Let’s explore these questions through stories.

What lies in the heart, is intent; when expressed in images, it can be a painting. Painting is like a heart print of the artist. They say that to appreciate a Chinese painting is to read it. A Chinese painter created his artwork with only the most economical of means: brush and ink on paper. The same means were used to create calligraphy. Western techniques of oil painting became prevalent in China only in the early 20th century. How to read a Chinese painting and how did it evolve? To answer these questions, one should remember that Chinese artists used the same basic materials throughout the centuries. Chinese painting is one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world.

The earliest paintings were ornamental and consisted of painted patterns of spirals, zigzags, dots, or animals. During the Warring States period (403–221 B.C.) artists began to represent the world around them. The invention of paper in the first century C.E. provided a cheap and widespread medium for both writing and painting and stipulated the course of their development. The water-based techniques and calligraphy became important, and artists chose a more graphical approach to the depiction of subjects in their paintings.

During the subsequent periods, artists portrayed mythological deities or honored funerary rites. Chinese landscape painting was established in the fourth century CE. During the Tang Dynasty (618–907) artists depicted an idealized landscape environment, with sparse numbers of objects. For example, we may visualize the Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains as a typical Chinese landscape painting. In the Song dynasty (960–1279), portrait painting became more sophisticated than before. It reached its maturity during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

The traditional Chinese painter tried to capture the inner essence, energy, life force, and spirit of his subject. The painting was not just a record of sensory experience but also a reflection of the artist’s mind. It was a revelation of his personality, and an expression of deeply held values.

Chinese painters did not aim to depict realistic images or ideal forms. For them, the fusion of picture and thought constituted the essence of art. That is why some of the most celebrated Chinese poets were usually both scholars and painters. Secular arts already flourished in China in the fourth century CE since rulers sought painters to lend prestige to their courts.

The Tang Dynasty painting tradition (618–907) bore many great painters. Some emperors became talented calligraphers and painters and embraced scholarly ideals. More often, they recruited artists whose images magnified the virtues of their rule. Depending on the political preference, a landscape painter may have shown a celebration of a well-ordered empire. An artist may have chosen to preserve his political integrity expressed in his portrait paintings.

Yan Liben (c. 600–673) was one of the great painters of the Tang Dynasty. He came from an aristocratic family and started his career in Taizong’s imperial court (r. 626–649). He was the main court painter for three reigns. Yan Liben was a scholar and became the prime minister under the emperor Gaozong (r. 649–683). Still, Yan Liben was mainly known for his ability as a painter.

The emperors may have treated Yan Liben well. However, the artist felt that he was not much more than a servant to the throne. On one occasion, an unusual bird had appeared in a lake in front of Taizong. He summoned the painter to sketch the bird. Yan Liben exclaimed: “I was known only by painting as if I were a menial.” He even advised his sons not to pursue an artistic career.

Chinese portrait painting aimed to memorialize, first and foremost, the rich and powerful. The most famous of Yan Liben’s painting is probably the series depicting thirteen Chinese emperors. Physiognomy, the art of discovering temperament and character from outward appearance, was very important for Chinese artists. They tried to represent emperors frontally. However, here the painter chose another approach for a different reason.

Yan Liben captured the individualized facial expressions and unique personalities of each of his subjects. The composition of the Thirteen Emperors conveys the hierarchy of scale, while contours suggest solid forms. The limited color palette, line drawing against the appropriate background enhance the dignity of the figures.

Xie He, another Chinese painter, also set an example for future artists in his Six Canons of Art. The painter formulated his canons in the sixth century C.E. An artist should “express the vital spirit of his subjects, outline their forms and depict their appearances with colors.” He also should carefully arrange them on the picture plane. By separating form and color into different laws, he described “the outline-and-color technique,” a distinctive feature of Chinese painting.

The Tang emperor was fond of horses and may have commissioned Yan to draw them as a design for carving. The popularity of horse painting reflects the importance that emperors placed on their stables. Expertise in judging fine horses had long been a metaphor for the ability to recognize men of talent. If one could find them, these men could be employed in the governance of the people. Yan Liben’s drawings also set the finest stone in the development of the sculpture of the Tang.

The Song Dynasty (960–1127) was a golden age for painting in China. One of the talented artists who painted horses during the Song rule was Huang Zongdao (active ca. 1120), one of China’s Master painters.

Stylizing the horse, flying gallop into space, Huang Zongdao used a great deal of imagination. The artist tried to capture the essence of the horse’s spirit as described in Xie He’s Six Canons of Art. Nevertheless, there is some formal resemblance of the image to reality. The painting of the horse is likely based on the artist’s observation of a real horse. Chinese people highly prized horses for their stamina and physical attributes. Superior horses were referred to as ‘dragon’ horses with supernatural abilities.

There is a great deal of symbolism in Chinese art and in paintings, in particular. Shifting to a more symbolic representation of the world, some Chinese painters focused on introspective contemplation. These paintings became so imbued with hidden meanings and could no longer be understood without the help of language. Trees, flowers and birds represented real-life objects, but also they started to represent symbols.

Painted in 1112, the Auspicious Cranes are attributed to the emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1126), whose description accompanied the painting. He wrote that one evening “auspicious clouds” suddenly formed in masses and illuminated the main gate of the palace. Then, a group of cranes appeared hovering above the palace and two of them perched on the roof.

Although this painting is based on a real event, it has a dreamlike atmosphere. While defining the subject, the artist took into account symbolic meanings that appear in many other similar works of art.

Cranes were a popular motif in Chinese painting. A crane is one of the most common symbols of longevity. They can signify Imperial China’s highest demarcation of court status. The cranes soar up to the blue sky, as though trying to reach the island of the Immortals. They reveal the painter’s wish for longevity and a solid foundation of any enterprise. The emperor hoped that heaven blessed his rule.

However, the luck turned away from the emperor Huizong. As a ruler, he was blamed for the collapse of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). He died in prison after the invasion of Jurchen, the competing forces, but he is still remembered for his contribution to art. The emperor Huizong helped to establish an imperial painting academy.

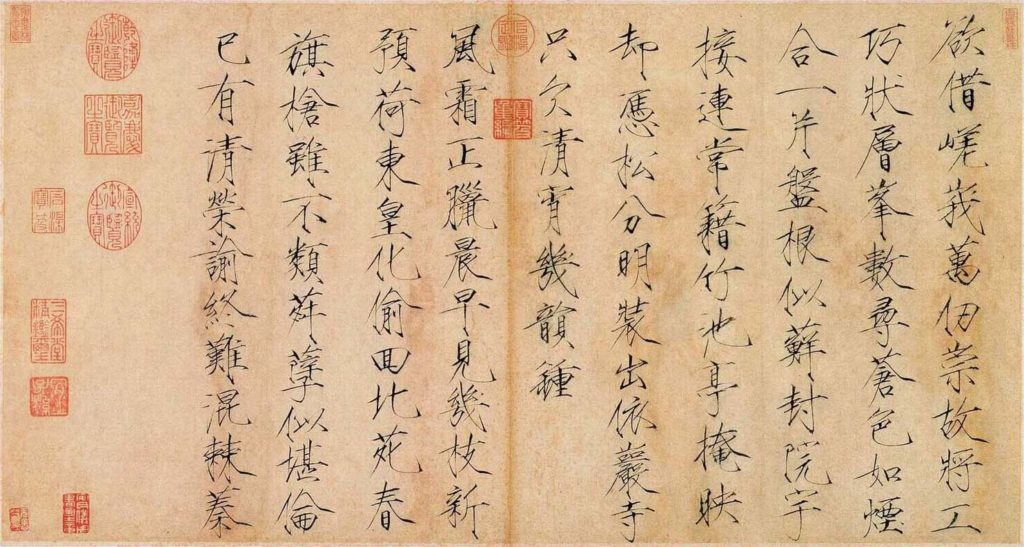

His academy tried to promote the gongbi technique or meticulous realism in painting. This technique delimits details very precisely, without expressive variation. Ma Yuan, one of the greatest Chinese painters, felt its influence. The emperor also created the Slender Gold style of calligraphy. If we compare the emperor’s style with Zhao Mengfu’s work, a famous 13th-century calligrapher, the difference becomes apparent. The emperor Huizong’s strokes are thin and may reveal his sensitive nature and weak temperament, whereas Zhao Mengfu’s strokes are full of force and dynamism.

Poetic and pictorial imagery work in tandem to express the inner state of the artist. Poetic inscriptions had become an integral part of a composition. The recipient of the painting would often add an inscription as his own “response.” A Chinese painter did not finalize his painting when he set down his brush. The painting would continue to evolve as later owners appended their own inscriptions. In this way, an artwork contained a record of its transmission that spans more than a thousand years.

The meaning of Chinese paintings is different from its Asian counterparts, for example, Indian or Thai ones. In many cases, Chinese painters depicted secular subjects with speed and movement, aimed for spiritual and representational purposes. As we saw, many subjects appear as though frozen in time. In contrast, a series of images in Indian art, for example, usually served as a storytelling device.

Considering all artistic achievements, the period of high symbolism did not become classical for Chinese painters. The classical period in Western art is based on order and structure, whereas not a single period in Chinese art can be considered as a classical one. When a Chinese artist adapted the style of an early artist, he more readily modified it by conveying new meanings. Then, he made a mixed style more personal. This approach draws a parallel with the early twentieth-century Western art with its strive for experimentation. For both Chinese and Western painters, artistic self-expression became a private experience.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!