Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

Sometime between 1948 and today, Christina’s World evolved from a painting into an icon. There are only a handful of American paintings that have made that transition – works like American Gothic, Nighthawks, and Whaam! have become similarly-ubiquitous cultural touchstones. Despite its popularity, Andrew Wyeth’s painting of Anna Christina Olson is the only one of these paintings that isn’t currently on public display.

Born in Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania, Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) was the youngest child of famed Treasure Island illustrator N.C. Wyeth. Deemed too frail to attend school with his siblings, Andrew studied painting and drawing in his father’s studio. N.C.’s emphasis on exhaustive, empathetic attention to subject matter no doubt sowed the seeds for Andrew’s eventual forensic style.

Wyeth also inherited his father’s affinity for transcendental philosophers Thoreau and Emerson, sharing their belief that the universal could be uncovered in the minute and mundane.

Almost all of Wyeth’s artistic career was spent in close observation of two places: the area in and around Chadd’s Ford, and Cushing, Maine. The people, nature, buildings, and interiors of the rural Northeast held Wyeth’s attention for seventy years.

In his own words:

I feel very strongly about the personal element of what I paint. I think that’s really the whole quality of my work. To go deeper into something that I know, intimately, throughout my whole life, and try to pull it out.

Biography: Andrew Wyeth Part 1 (1980). Posted by Antiquaria via Youtube, Oct 20, 2017.

It was this dedication to place and to realism that would invite so much admiration and an equal measure of critical neglect.

Acquired by MoMA soon after its creation in 1948, Christina’s World bears the hallmarks of a classic “Wyeth.”

Two plain farmhouses sit at the crest of a dun-colored hill in rural Maine. In the foreground, a woman lies on the ground, propping herself up on her arms and facing away from the viewer, up the slope to the farm buildings. Her dress is “pink, like faded lobster shells that you find on the shore here”.

The subject matter is unassuming enough. The composition, while well-balanced and active enough to keep the eye moving from Christina to the farmhouse, barn, and back, is not groundbreaking.

To the unsympathetic viewer, Christina’s World could represent nothing more than kitschy, picture-postcard yearning for pastoral bliss – a criticism regularly leveled at Wyeth throughout his career.

As with so many of Wyeth’s works, a closer inspection is required.

Still from the video, from framing “Christina’s World” to a Wim Wenders Q&A, 2015, MOMA, New York, NY, USA.

Each blade of grass is picked out in meticulous detail. Wyeth favored egg tempera paint, a quick-drying medium that fell out of favor with the arrival of oil paint in the 15th and 16th centuries. He compared the thin layering technique associated with tempera to “the way the earth itself was built”. In painting the forensically-detailed landscape for Christina’s World, he saw himself “building the whole planet she was finally going to exist in.”

Andrew Wyeth, Christina’s World, 1948, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, USA. Detail.

Another look at Christina’s figure reveals that she hasn’t been spared the dry, wan effect that tempera has on its subjects. The muted pink of her dress is echoed in similar tones around her fragile elbow and wrist, meanwhile strands of hair around her crown link her to the straw colors of her landscape.

Her hands, partly hidden by veils of grass, are dry, knobbly, and clutching at the ground. It is in these details that Christina’s World – and Christina herself – reveal themselves.

The eponymous Christina was actually named Anna Christina Olson. Introduced to Wyeth by his wife, Betsy, Olson lived in a farmhouse near the Wyeth home in Maine. She, her brother Alvaro, and even their home would become pillars of Wyeth’s oeuvre – featuring regularly in portraits and landscapes. The artist became so close to the family that he set up a studio on the second story of the Olson farmhouse.

Andrew Wyeth with Anna Christina Olson and her brother Alvaro at their farmhouse in Cushing, MN, USA.

Anna Christina had Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease, a neurological condition causing muscle loss. By the time Wyeth met the Olsons, she had lost the use of her legs. Refusing to use a wheelchair, she instead pulled herself around the farm and house.

Seeing her in a field from his studio at the Olson house, Wyeth was inspired to compose Christina’s World. For him, the painting represented “her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless.”

Some critics have labeled Christina’s World controversial for Wyeth’s decision to model the figure’s body on his wife Betsy, rather than Anna Christina herself. He has been accused of “beautifying” the scene and masking disability to serve a rural ideal.

Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World, 1948, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

For his part, Wyeth claimed that “Christina’s World is more than just her portrait. It really was her whole life, and that is what she liked in it.” Furthermore, Anna Christina did like the painting, saying that “Andy put me where he knew I wanted to be. Now that I can’t be there anymore, all I do is think of that picture and I’m there.”

This doesn’t absolve the work from accusations of “masking” disability. Wyeth expressed conflicting views on that very subject. When speaking about his early life studies of Anna Christina, he claimed that:

…my cold eye took in the deformity and it shook me. I hadn’t thought about the deformity. She was so much bigger than all the little idiosyncrasies… If you really are profound about a thing and really see its essence, you don’t have to have a prop like a deformity.

Rethinking Andrew Wyeth, edited by David Cateforis, 2014, University of California Press.

Why, then, did he not model the entire figure on his wife? The Christina of the painting is, as Randall C. Griffin puts it in his essay on Christina’s World, “a hybrid figure”, describing her thin arms as if “emerging from a different painting, one that peels back the scene’s sunny illusion.”

Christina’s Word continues to split opinions on its treatment of disability. For sympathetic observers, the effect of the “hybrid figure” is a heightened awareness of Anna Christina’s condition, and an attempt to overcome reactions that might not initially see beyond her CMT to her personality. Meanwhile, for critics it is an attempt to gloss over her condition in service of aesthetics.

Beyond Christina’s World, Wyeth painted unsparing portraits of Anna Christina, her brother, and countless other figures at the fringes of rural society. Portraits like Anna Christina, Oil Lamp, Grape Wine, and Anna Kuerner are frank depictions of introspective subjects, as forensically observed in Wyeth’s tempera landscapes.

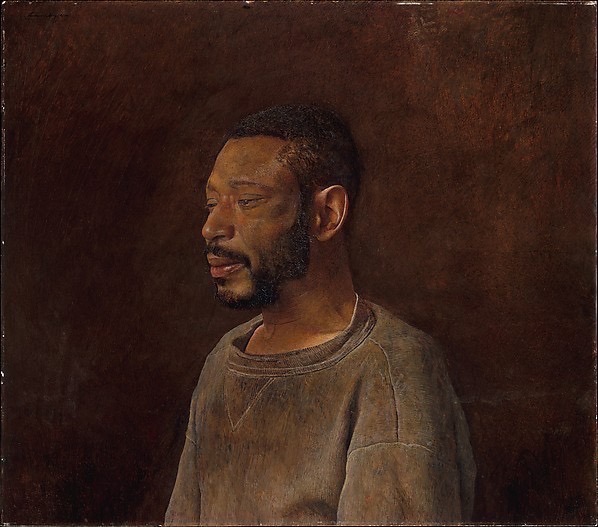

Andrew Wyeth, Anna Christina, 1967, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

His figures are stark and totemic, but they are not glorified for being beautiful pastoral ideals. They are instead glorified for being deeply-embedded reflections of their home landscape. They happened to share that landscape with Wyeth, who canonizes them – and the tree stumps, cowsheds, and bland fields – by paying them close, transcendental attention.

Andrew Wyeth, Grape Wine, 1966, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Wyeth acknowledged the ways in which his work was interpreted:

People make me the American painter of the American scene.

Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self-Portrait, lecture recorded May 18, 2014. National Gallery of Art.

Whatever the man himself believed, his painting is no more an advertisement for a bygone country lifestyle than Edward Hopper’s heavy emphasis on isolation is a recommendation for urban living.

In fact, Hopper – an artist widely accepted in the American modernist art story, and an admirer of Wyeth’s work – shares more with the rural painter than many would like to admit. Mark Rothko identified it for himself, writing that both Hopper and Wyeth’s work was about “the pursuit of strangeness.”

Despite recognition from fellow artists, Wyeth was pitched against Abstract Expressionists like Rothko himself. Epochal critics like Clement Greenberg cast Wyeth as a wilfully unmodern artist, wrong-headedly dedicated to rural realism at a time when urban (mostly New York-based) abstraction was building American art’s credibility on the world stage.

Whatever nostalgia there is in Wyeth’s work, it does not demand a return to the fields, though. His painting is more concerned with the twilight of that land and lifestyle which formed a very real part of his day-to-day experience. As Thomas Hoving, former Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art put it:

Wyeth didn’t paint a single sentimental picture in his life…[he] painted like a surgeon cuts. Crisp, flinty-eyed, and completely unsentimental…what’s really there is what you see.

Wyeth was more concerned with the present than critics concerned with promoting New York – the nexus of America’s thrust into the international (and therefore validated) modern art world – have given him credit for.

The Olson farmhouse, Cushing, ME, USA. Photograph by John Greim.

Rather than sideline the subjects of paintings like Christina’s World – those rural figures that still made up close to 40% of the US population by 1950 – Wyeth made them his focus. It is part of what made his art, in Andrew Brighton’s words, “populist, rather than just popular.”

The painting continues to inform and inspire newly-minted American icons. Recently, the videogame series The Last of Us featured a version of the Olson farm and the final season of Donald Glover’s Atlanta included an episode entitled Andrew Wyeth. Alfred’s World.

Despite the critical rejection, Wyeth remains a pillar of the American art story.

Author’s bio

Alex Cohen is a UK-based freelance writer. He has an MLitt in the History of Art from the University of St Andrews.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!