Art on Screen: 12 Movies about Artists Worth Seeing

Whether troubled or exciting, extraordinary or perfectly average, the lives of artists are an endless source of inspiration for cinematographers.

Edoardo Cesarino 17 February 2025

World War II ravaged everything in its path. The global economy was ruined, and many cities were completely destroyed, not to mention the number of people who lost their lives, were severely injured, or lost their homes. The world resembled post-apocalyptic scenery. Of course, arts didn’t escape this catastrophe. Modernism suffered from the moment the Nazi Party gained power. After the war, the movement had to rebuild and reinvent its identity. After all, it was always based on society’s needs and problems. Thus, it took this direction again. Italy, one of the most politically, financially, and socially ruined countries of the war, showed a great artistic recovery both in art and cinema. Italian Neorealism became one of the most distinctive branches of postwar Modernism and of great value.

After the war, a considerable amount of Europe’s younger generation turned its interest towards a more artistic and less standardized cinema. This encouraged the appearance of art cinema. There were many elements of older artistic movements, such as French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage. For Instance, Italian Neorealism adopted a Soviet technique in which amateur actors were used for leading roles, in order to make the acting rawer. On the other hand, Scandinavian directors were deeply influenced by Expressionism. However, this new art cinema didn’t stick to traditions but embraced experimentation.

Actually, postwar cinema doubted the social and moral values of the early 20th century. Its major characteristic was the abolition of typical narration, as Hollywood cinema had established it. From that moment, the movies turned around a certain issue or a psychological problem, not a story. Of course, this didn’t mean that there was no plot or interesting characters, but rather they were underdeveloped. After all, the main focus was a specific subject or an idea. The turn to psychology and philosophy put European postwar cinema at the center of postwar thought in general (Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, Eugène Ionesco, etc).

Another characteristic of postwar Modernism in cinema is aesthetic freedom. That is the freedom of the camera to move into space or the radical use of sound. The heavy musical background stops (eg. the violins playing during a romantic scene) and the sound sources become visible, eg. the music from a radio. Often the music is used to express something opposite to the situation. For instance, in the movie Ladri di Biciclette (The Bicycle Thief), even though it is a good thing that the protagonist found a job, the background music is sad, as if he is not going to keep it for long.

During the 1930s, Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime used cinema for propaganda. This was a common move of every totalitarian regime. So, in 1934, Mussolini created ENIC, a central organization that consolidated the production and exhibition of films into one big entity. At the same time, he established the Film Festival in Venice, which took place with his support until 1940. In 1935, he founded a film school, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, and began the construction of Cinecittà, an enormous film studio. It was the only studio with the technical potential to compete with Hollywood. Also, in 1940 Mussolini forbade the import of all American movies.

The Italian production that flourished those years can be separated into two categories: historical drama and white telephone films. The latter was a sub-genre of melodrama. They depicted the Italian upper class’ emotional unrest, symbolized by a white telephone in luxurious settings.

The circumstances allowed many directors to familiarize themselves with the new means. Thus, when fascism collapsed, they had all the necessary knowledge to finally create their personal vision.

After the liberation in the spring of 1945, everyone wanted to move on and forget the past. The left and liberal parties in Italy formed a coalition government in order to help the country’s rebirth. In cinema, it took the form of Italian Neorealism. However, all the studios were destroyed during the war, even Cinecittà’s. So, how were they better than the previous ones?

First of all, the main intention of Italian Neorealism was to abolish fake magnificence. That is, tough reality became the focus of the movies, combined with a critical point of view of recent history. Moreover, the directors began shooting outside, in the real environment. Plus, as aforementioned, they gave leading roles to amateur actors.

Roberto Rossellini is one of the most prominent directors of the movement. He managed to turn all the disadvantages of the post-war cinematic industry into elements of Neorealism.

Roma Città Aperta (Rome, Open City) is the first movie of the movement. It was directed in 1945, only a few weeks after the Nazis left the city. It is the story of the Italian resistance leader, Georgio Manfredi, who tries to hide from the Nazis during the occupation in 1944.

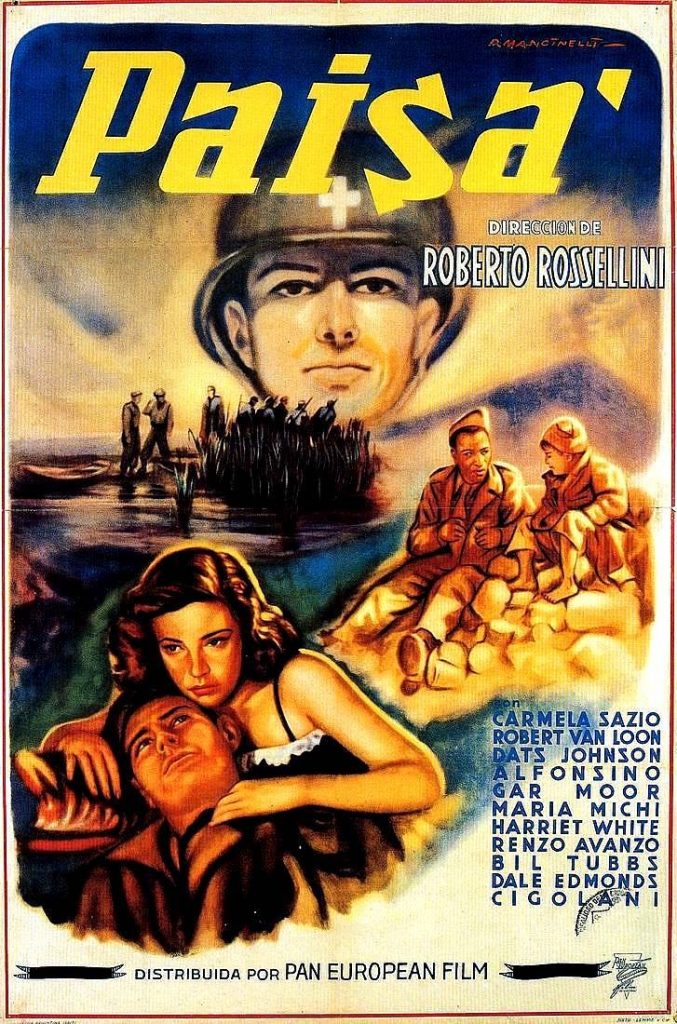

The movie is a milestone for the movement. There is no cinematic infrastructure, let alone a budget to build scenery or hire professional actors. Of course, the perfect studio lighting was non-existent. Rossellini used all these characteristics to create a raw and true movie. Other films by Roberto Rossellini are Paisà (1946), Germania, anno zero (Germany, year zero, 1947), La machina ammazzacattivi (The machine to kill bad people, 1948), etc.

Vittorio de Sica is the second most important director of the movement. In the 1930s, he played in white telephone films and directed light comedies. In the 1940s, he turned to Neorealism. Under the influence of his friend Cesare Zavattini, he created many movies. The most distinctive is Ladri di Biciclette (The Bicycle Thief, 1948). It is a strong social document about the story of a worker whose life depends on his bicycle. The movie shows his relationship with his son and it portrays the cruelty and greediness of the post-war era.

Another great movie is Umberto D. (1952). It is about a poor man in retirement who tries to live decently with his dog in financially harsh conditions. Umberto resembles a Charlie Chaplin hero, a tiny man feeling adrift in a hostile environment.

Italian Neorealism’s bloom was very short-lived. It only lasted from c. 1942 to 1948. It is true that these movies did not have a big audience. The government didn’t approve of those movies because they portrayed a decadent and immoral Italy. The left parties didn’t like their pessimism and lack of political engagement.

However, Italian Neorealism was the first movement to turn away from Hollywood and it became very innovative. It sowed the field for another generation of directors. They rose in the 1950s and 1960s, as successors to Neorealism. The movies became psychological. The main characters belong to the middle class and they are not trying to solve their bread-winning problems. They tried to find a meaning to life in a society of post-war consumerism and technological evolution. Michelangelo Antonioni (L’ Avventura, 1960, Blowup, 1966, etc), Federico Fellini (La Strada, 1954, Le Notti di Cabiria, 1957, La Dolce Vita, 1960, etc), and Luchino Visconti (La Terra Trema, 1948, Rocco E I Suoi Fratelli, 1960, etc) are only a few directors to name.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!