Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

American sculptor Claire Falkenstein (1908–1997) was highly successful in her days, but today her story rarely resurfaces on the pages of art history books. So, let’s re-discover this erased artist!

She was already brilliant as a student. Born in Coos Bay, OR, in 1908, Falkenstein moved with her family to Berkeley, CA, where she attended university. She had her first solo show in 1930, while still a student, at the East-West Gallery in San Francisco. And she hadn’t even had any formal training at that point! After her success, she was invited to study under Alexander Archipenko who introduced her to the world of the Russian avant-garde, where she met such stars as Naum Gabo, and the Bauhaus teacher László Moholy-Nagy. During these early years, she worked mainly with clay to create abstract ceramic sculptures, and later she progressed to the exploration of wood as a sculptural medium. Her works from the 1940s seem usually like a single, unified mass but can also be broken down into discrete elements and they were intended to be taken apart and reassembled by the viewer. Falkenstein called them “exploding volumes.”

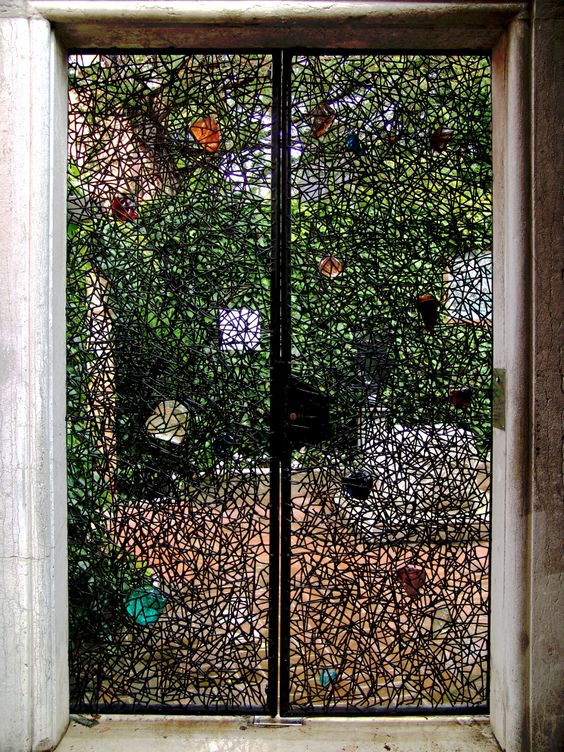

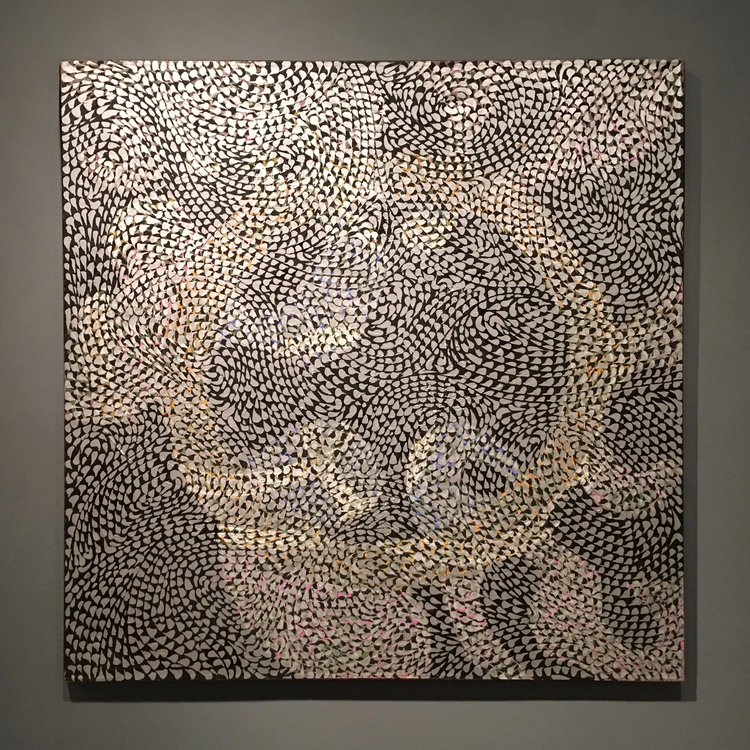

By 1950, Claire Falkenstein had moved her sculptures onto new materials again, this time it was plastic, aluminum, glass, and wire. Then, at the age of 42, she moved her studio to Paris, where she associated with Jean Arp and Alberto Giacometti. It was in Paris where she developed the aesthetic that she would use throughout her career: the open wire sculptures that emphasized the presence of negative space, articulated by organic forms, color, and light interlocked together. Peggy Guggenheim commissioned Falkenstein, whose career gained velocity in the 60s, to produce the entry door to the Palace Venier dei Leoni in Venice where Guggenheim lived. Composed of wire and Murano glass, the door brilliantly illustrates Falkenstein’s interests in nature, art, and science, and how the three can interact and be combined. Falkenstein herself described her method to make this door an “infinite screen” in which small modules of metal can expand infinitely, precisely like the universe. Michel Tapié, a French critic, described that:

In her hands the webs become almost a raw material, created to fit her needs, that she either hollows out, or hammers, or welds along lines of stress and at essential points with great architectural lyricism and baroque profusion of inventiveness.

– In: Harry Rand, The Martha Jackson Memorial Collection, Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution, 1985.

While in Europe, she received several large-scale commissions, such as the railing of the Galleria Spazio, Rome (1958), or the Palazzo Venier de Leoni gates, which now houses the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (1961).

She returned to California, in 1963, and began receiving other commissions like a monumental fountain Structure and Flow No. 2 (1964-65), now destroyed, which once stood at the corner of Wilshire and Hauser boulevards, and a fountain at the Long Beach Museum of Art; outdoor sculptures for reflecting pools at Cal State Long Beach and the San Diego Museum of Art; and the ornamentation over the entry to physical education building at Cal State Fullerton. With time, she could not sustain her work with hard and heavy materials, so she shifted away to painting. In 1997, she died in Venice, California, at age 89.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!