5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

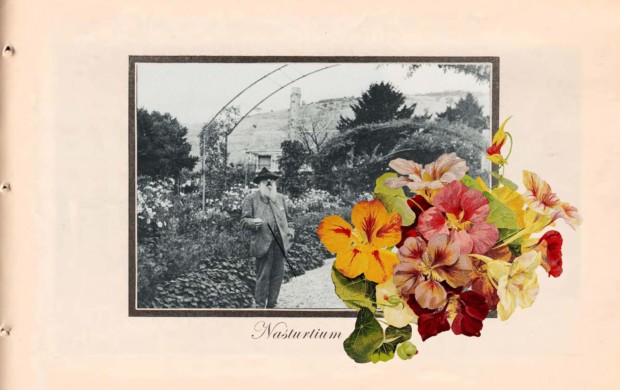

Famous Impressionist artist Claude Monet‘s garden in Giverny has been one of the must-see sights for every art lover visiting France. It is a flowering domain where the artist had spent the last 40 or so years of his life, digging, planting, weeding, and painting.

As a young man, Monet always enjoyed the outdoors. He had spent his entire youth moving from town to town along the river Seine. But wherever he lived, he planted flowers. He justified his obsessive garden-making on the grounds that flowers gave him a subject to paint while he was indoors. But in truth, his flowers accompanied him during times of emotional toll, artistic frustration, and financial hardship during his career.

In May 1883, Monet and his family moved to Giverny, a small village about fifty miles west of Paris. He rented a large house which came with an ample-sized garden with alleyways of cypresses and orchards of various fruit trees. The garden needed immediate attention. The amount of work to bring it to the state of Monet’s taste was a handful.

With the help of his family, he changed its appearance from a farming plot to a flowering garden. Around the house, he sowed seeds for his favorite annuals: poppies, sunflowers, and nasturtiums. In springs he would plant daffodil bulbs, primroses, and willowherbs. With his gardening friend, Gustave Caillebotte, another Impressionist painter, they swapped seeds and cuttings, exchanging advice and expertise on handling flowers.

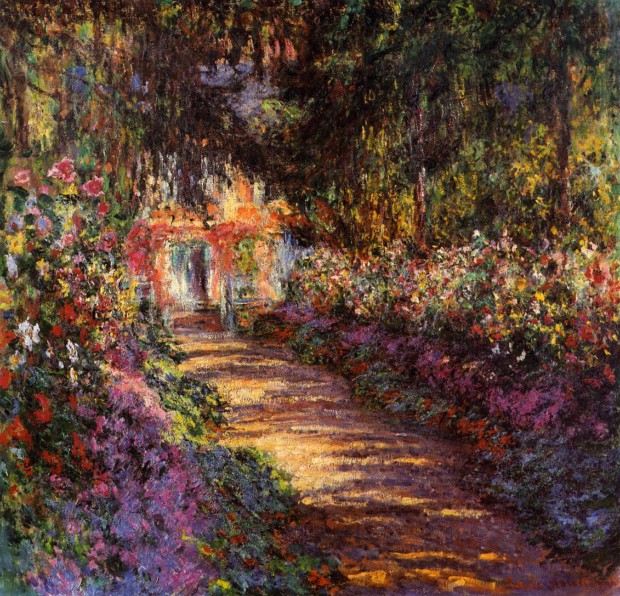

By the late 1880s, Monet started gaining substantial popularity, both in Europe and across the Atlantic. In November 1890 he could finally purchase the house. Now on his private land, he embarked on a much more ambitious gardening plan: he hired two full-time gardeners, which would eventually grow to six, built a large greenhouse just to propagate species and reserve bulbs, and rented a separate garden, not far away from his house, to move all the vegetable and fruits, so he can devote his own garden solely for his flowers. His flower collection grew with a more extravagant range of species, which must have cost him a fortune: irises, peonies, delphiniums, Oriental poppies, asters, and many species of sunflowers.

Unlike structured and rather linear French gardens, Monet’s one was acquiring more English style. Instead of spacing them apart, he covered every inch of the bed with foliage and annuals, perennials, and biennials. As a result, it was a garden curated through the eyes of an artist. He planted the flowers with such meticulous consideration and planning – when some withered, others would bud, just in time to provide fresh combinations of primary and contrasting hues. Speaking of colors, he chose to paint the front of the house pink and the shutters green – his favorite combination – giving it the iconic look we all came to know now.

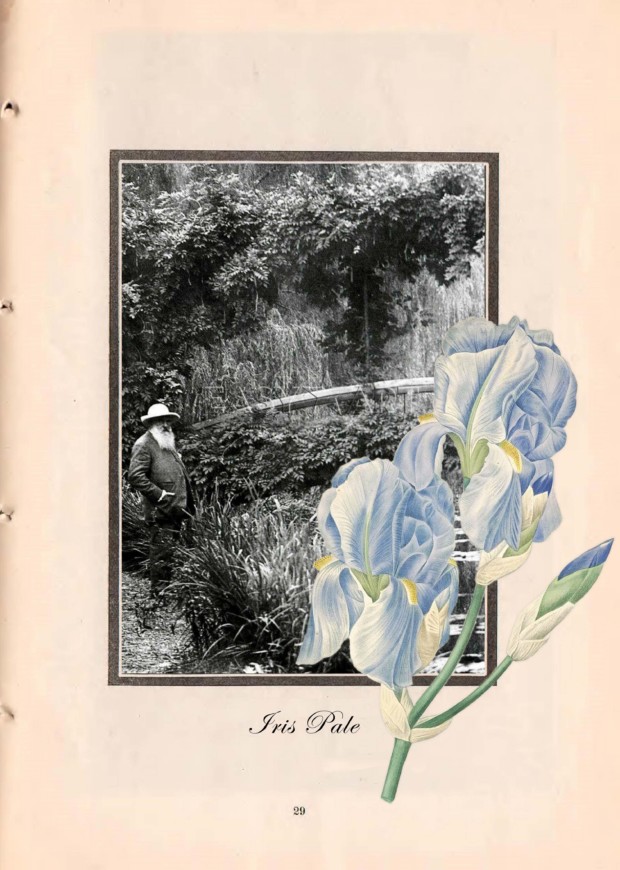

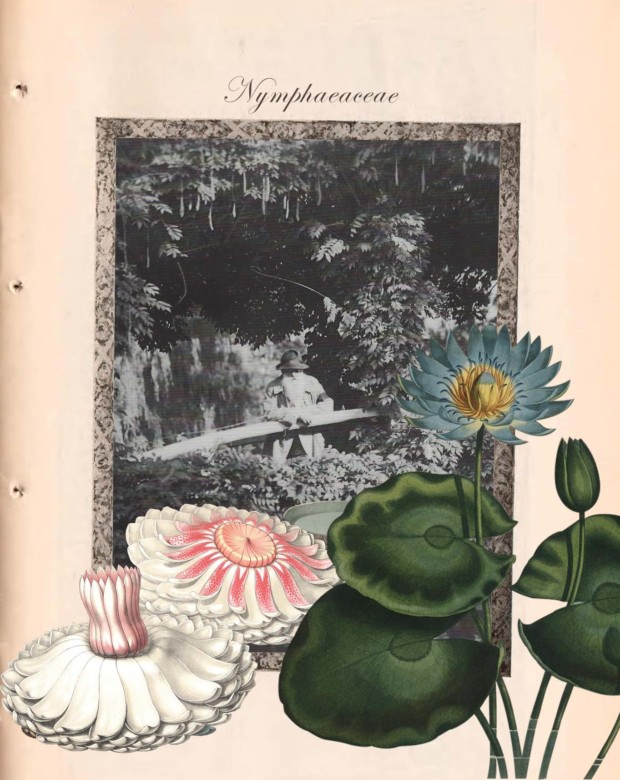

For a gardener with such an insatiable thirst for blooms and greenery, enough will never be enough. Once he was happy with his flower garden, he started casting his eyes across the road where there was a marsh with a small pond used by local farmers to water cattle. It seemed like a perfect place to plot his dream of having the Oriental floating garden. But, it didn’t come easy. First, the land was separated from the domain by a railroad and a major street. Second, the locals objected to his plan with such a fervour that, bonded with the authority, delayed the process of acquisition as much as possible. He bought part of the coveted land in February 1893. But he had to deal with a lengthy chain of bureaucracy just to convince the locals his exotic plants will not intoxicate the water supply. He grew so frustrated, that, whilst away in Rouen he wrote to his wife:

This enrages me and I want no longer to have anything to do with… all those people in Giverny. There is nothing but trouble ahead, believe me, I give it up completely. Don’t rent anything, don’t order any lattice, and throw the aquatic plants in the river; they’ll grow there. I want to hear no more about it, I want to paint. Shit on the natives of Giverny, and the engineers. I’ll give the land to whoever wants it.

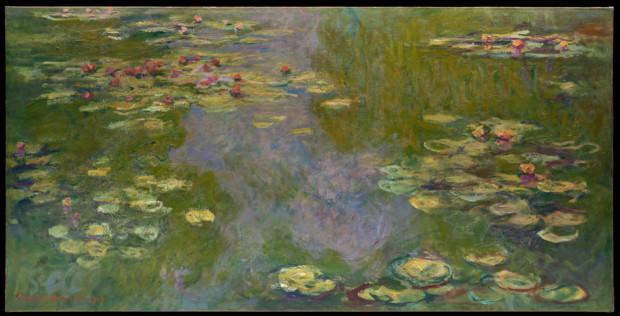

Despite this brief despondency, he received his authorization to build his water garden in July 1893. Now he was content. By 1895 two Japanese bridges were up, various breeds of Irises, such as Siberian Snow Queen, were surrounding the shores of the pond and bamboo grew tall at the rest of the territory. Meanwhile, a firm of Marlac started crossing different species of water-lilies and bred new collections with shades of red, pink, purple, and lavender. How could Monet resist!? He went on a spree buying the newest species, such as Arethusa, Atropurpurea, and James Brydon.

It will become a sensation across Europe, both among gardeners and artists, and will be continuously reported in various journals, magazines, and newspapers. But this was only the beginning of a new chapter in Monet’s artistic life. After he completed the development, he devoted the last 30 or so years of his life to creating almost 250 panels depicting the serene surface of his water-lily pond. He also developed an idea of creating a space with giant panels covering the walls, where one can submerge into the tranquillity of his garden.

Although he didn’t live to see the realisation of his idea, the state of France built a pair of oval rooms at the Musée de l’Orangerie to permanently house eight of Monet’s water-lily murals. The exhibition opened to the public on 16th of May 1927, a few months after Monet’s death. Today, thanks to Google Art Project, we can virtually visit the rooms at the museum. The interactive tool allows you to freely walk in between the spaces, zoom into the panels and take your time exploring the murals.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!