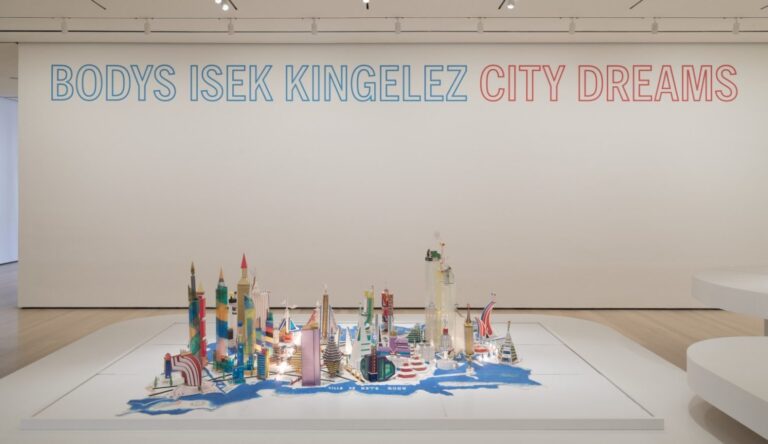

The color was overwhelming. I was on the third floor of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, visiting an exhibit called ‘Bodys Isek Kingelez: City of Dreams.’ Kingelez was a sculptor of architecture who lived in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, previously known as Zaire, and previously known as the Belgian Congo before that. His dream was to create a “better, more peaceful world.” He was not an architect. He was laying the groundwork for the architects of the future, a future that would not be possible without his vision (according to Kingelez).

Approximately one-third of the works of Kingelez are being displayed in this exhibition, which will be open until January 1, 2019. In addition to the “extreme maquettes,” as Kingelez liked to call them, there was a virtual reality tour of Ville Fantôme, one of the artist’s most famous pieces (from 1996), and a documentary about Kingelez that was very informative. I waited on a long line to see the virtual tour; I put on the headset, looked around, and saw oranges and blues and yellows that were swirling around me, full of chroma. The colors were too noticeable, so I didn’t feel as if I were in a peaceful world. As a result, I felt agitated. I took off the headset and returned to the exhibit. The maquettes were small; many of them were busy with buildings. There were so many colors and so many buildings and so many maquettes that I didn’t know what to look at first, or what any of it meant. The exhibit was intriguing enough for me to want to find out more.

My first reaction was that the colors of the buildings were colors that a child would use—bright colors with no subtlety. And the description of a “better, more peaceful world” could very easily have come from the mouth of an innocent child. But then, when I watched the documentary by Dirk Dumon (Kingelez: Kinshasa, un ville repensée <A City Rethought>), I realized that Kingelez did not have the innocence of a child; he was more jaded and critical than that. He was supremely confident in his abilities and his place in the art world. And as I watched more and saw the environment he lived in, I could see the colors of his works in the buildings around him. Suddenly the colors had a different meaning for me. I had been looking at the colors from my perspective, from my life experience, but now I was able to relate more to Kingelez and I was able to see these colors through the eyes of Kingelez. These are the colors and the combination of color he had been exposed to for most of his life.

The catalogue for the exhibit, which was edited by Sarah Suzuki, the exhibit’s curator, sheds more light on Kingelez the artist. The maquettes are beautifully photographed; here the colors appear more harmonious and beautiful than they do in person and in virtual reality. Ms. Suzuki refers to Kingelez as one of the unsung visionary creators of the twentieth century.

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”500″ identifier=”1633450546″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/51YhsX3wZuL.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”404″]

Suzuki writes about color in the catalogue, noting that:

the symbolic meaning of color was as carefully considered by Kingelez as it had been by Mobutu. The first iteration of the president’s flag was blue with a yellow star and a red diagonal stripe, with red symbolizing the blood of the people’s sacrifice; yellow, prosperity; blue, hope; and the star, unity.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has undergone major upheavals since the birth of Kingelez in 1948. Belgian colonialism ended in 1960. The dictator Mobutu reigned from 1965 until 1997.

As MoMA’s description of the exhibit says:

Kingelez’s vibrant, ambitious sculptures are created from an incredible range of everyday materials and found objects—colored paper, commercial packaging, plastic, soda cans, and bottle caps—all meticulously repurposed and arranged.

One of his buildings was inspired by the brand of beer that he enjoyed drinking. The blue packaging of the beer became the color of the building that the beer was represented by.

Ironically, on the same floor of the same museum as the Kingelez exhibit is another exhibit, ‘Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980.’ This Yugoslavia exhibit is in many ways the polar opposite of the Kingelez exhibit.

The most important difference is that color is absent in the architecture of Yugoslavia; this absence means that the focus is on form. Many of the forms are beautiful in their simplicity. The same rectangular shapes repeat themselves over and over again, which is sympathetic with the idealized Communist viewpoint of equality for everyone. In the National and University Library of Kosovo, for example, a seemingly infinite number of three-dimensional rectangles are covered by half-spheres. Even though some rectangles and some half-spheres are smaller than others, all of them are able to live equally and harmoniously in this architectural world. While many of the buildings in the Yugoslavia exhibit are beautiful to look at, I don’t know how peaceful I would feel if I were living in one of them.

Sadly, Bodys Isek Kingelez died of cancer in 2015. He was only 66 years old; August 27 would have been the artist’s 70th birthday. He did not live to see his dream of a better and more peaceful Zaire (or a better and more peaceful Democratic Republic of the Congo) materialize through the world that he had visualized. Kingelez’s ideas have lived on, however, and in a country that has changed so much over the past 60 years, who can deny the possibility that in the years to come, the Democratic Republic of the Congo may grow to resemble Kingelez’s vision after all?

Find out more:

Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams

Through January 1, 2019

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”377571054X” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/514MHJ8TVNL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”116″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0262640694″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/51GdTCFR6YL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”109″]