5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Step into the world of Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000) as we explore his 5 extraordinary works of art and architecture bursting with colors and creativity. From his role as a painter and printmaker to his visionary approach as an “architectural doctor” and ecological activist, Hundertwasser’s colorful masterpieces continue to captivate audiences worldwide.

Influenced by the Vienna Secession movement and inspired by artists like Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, his vibrant works are considered key contributions to post-war modernism. Embark with us on a journey through the colorful visual realm of this inspiring artist and visionary.

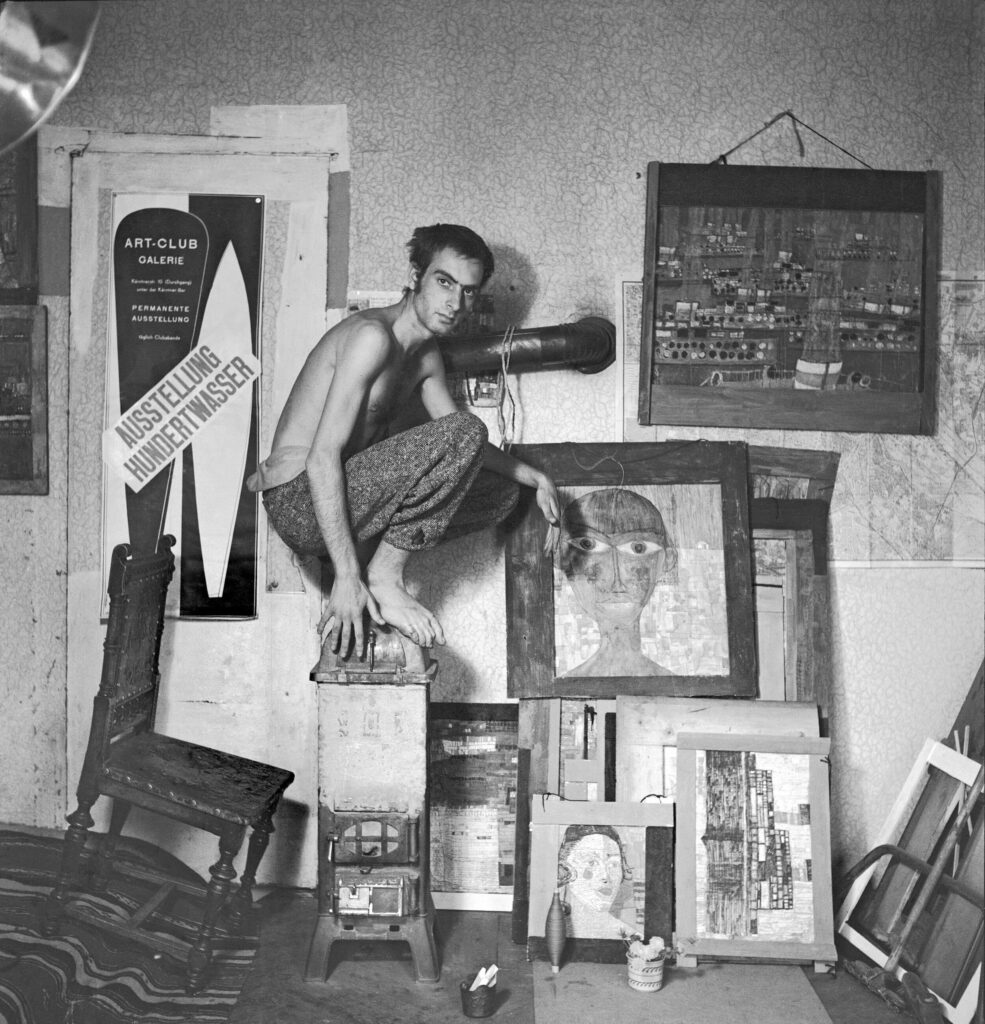

The Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser at his atelier, around 1952. Photograph by Helmut Baar.

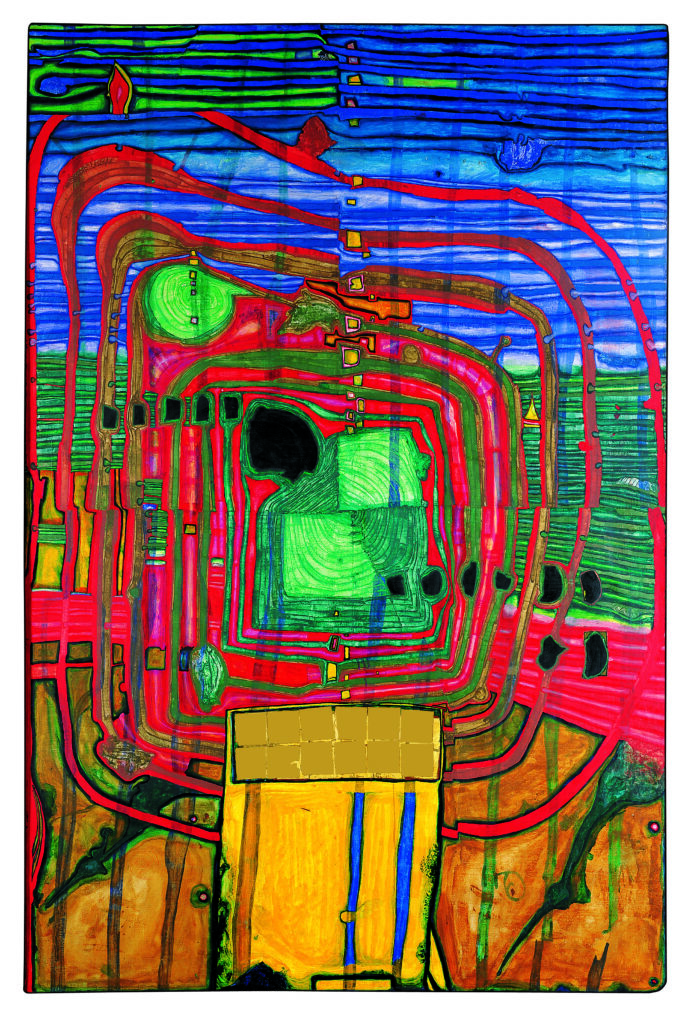

A significant aspect of the effect of Hundertwasser’s painting is color. Hundertwasser uses colors instinctively, without associating them with any symbolism, either traditional or self-invented.

Hundertwasser – Kunst Haus Wien (Cologne, 1999)

In Hundertwasser’s paintings, two prominent motifs dominate the visual narrative. The first revolves around organic forms reminiscent of vegetation, evoking a connection to nature. The second motif category features recurring architectural elements such as houses, windows, and fences. What’s fascinating about Hundertwasser’s artistry is how these two motifs intertwine seamlessly.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Hommage au Tachisme, 1961, Kunst Haus Wien, Vienna, Austria.

Hundertwasser’s fondness for radiant color and bold contrasts is evident in his artwork. He strategically juxtaposes complementary hues to accentuate dynamic elements like spirals.

Additionally, he also incorporates gold and silver foil directly onto the canvas. Through a skillful blend of oil, tempera, and watercolor techniques, he achieves a striking interplay between matte and luminous sections.

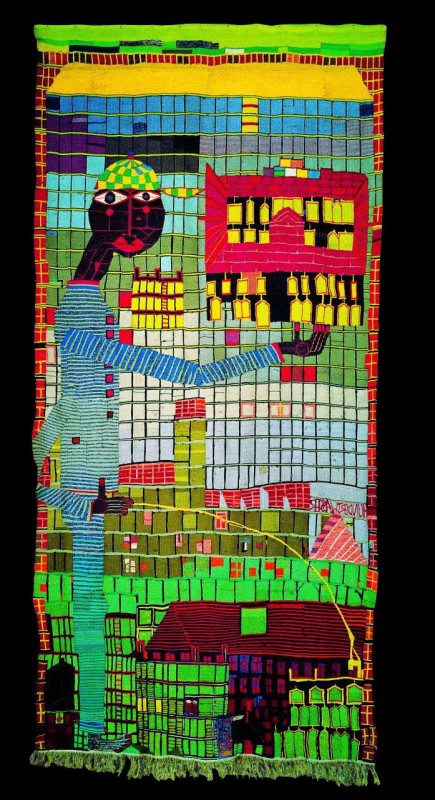

Like his paintings, Hundertwasser used radiant colors and bold contrasts to create tapestries. In 1952, his pioneering tapestry, Pissing Boy with Sky-Scraper, emerged from a bet challenging him to weave a tapestry without a cardboard template.

Subsequent tapestries, woven by artisans of his choosing, followed the same template-free process, ensuring the distinctiveness of each piece.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Pissing Boy with Sky-Scraper, 1952, Kunst Haus Wien, Vienna, Austria.

For Hundertwasser, it was crucial that weavers implement their personal artistic flair into the process. This allowed them to create unique interpretations of the model. He contended that this approach infused the artwork with vitality, shunning the notion of producing mere replicas. Consequently, all of Hundertwasser’s tapestries are singular creations without mass-produced editions.

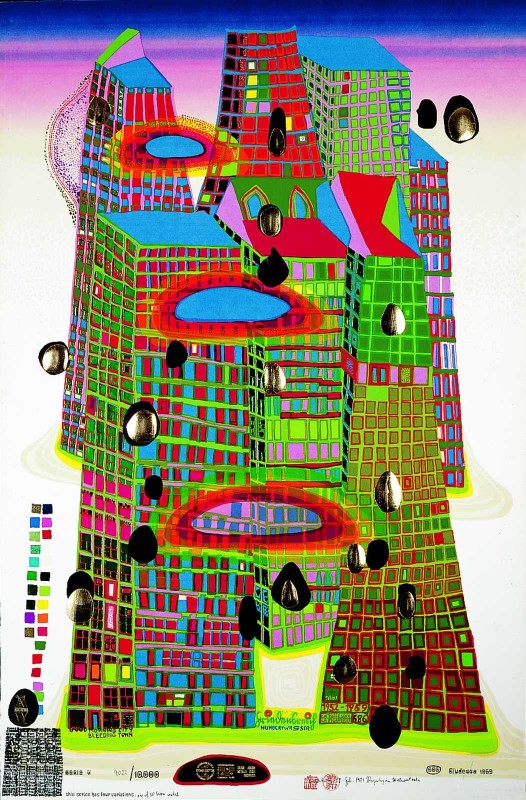

Clearly, Hundertwasser’s artistic career encompassed a wide range of media, including graphics. He aimed to revolutionize the art of original graphics by creating several unique pieces within each edition. This challenged the monotony of machine-produced chain production. Collaborating closely with printers, he devised an innovative system to generate diverse color and form variations, ensuring each print retained its individuality.

Hundertwasser developed many graphic techniques, including lithography, silk screen, etching, color woodcut, and mixed media. He also pioneered the exploration of new methods and the utilization of unconventional materials. The artist’s innovative approach marked him as a trailblazer in the field, pushing the boundaries of traditional graphic art.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Good Morning City–Bleeding Town, 1970-1971, Kunst Haus Wien, Vienna, Austria.

In his work Good Morning City–Bleeding Town, he employed new methods in print graphics such as metallic-stamp printing, luminous colors that glow in the dark, reflecting glass-bead appliqués, and a multitude of color overprints. He even painted each color separately on transparent foil before transferring them onto the screen, showcasing his unparalleled creativity and technical prowess in graphic art.

In the early 1950s, Hundertwasser turned his attention towards architecture, embarking on a quest to redefine it with a more human-centered approach aligned with nature. He wished to reject the rigidity of rationalism and the confines of functional architecture. Hundertwasser advocated for designs that eschewed straight lines in favor of organic, harmonious forms.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Hundertwasserhaus (view of the façade), 1983-1985, Vienna, Austria.

One of his most famous creations, which certainly follows these ideas, is Hundertwasserhaus. While encountering it from the world of rigid white and gray constructions, the viewer is overwhelmed with its bold colors and organic body. The façade is made of colored finishing plaster that allows various ornamentations.

Even more so, the residents are encouraged to garnish the outer part of the wall as well and to “mark” their living space. In that way, they are carrying out the building’s leading idea—“to eliminate anonymous perfectionism.”

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Hundertwasserhaus (detail), 1983-1985, Vienna, Austria.

Hundertwasser worked as an ‘architectural doctor’ – a profession of his own invention whose calling is to modify and beautify existing structures, structures sterile and soulless in character.

Hundertwasser (Köln: Benedikt Taschen, 1993), 170.

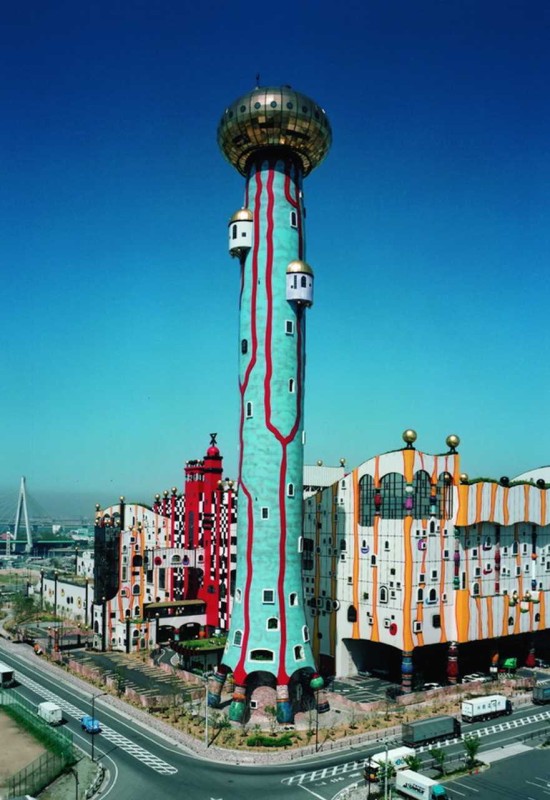

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Maishima Incineration Plant, 2001, Osaka, Japan.

Hundertwasser completed more than 40 architectural projects worldwide, including two waste incineration plants: the Spittelau plant in Vienna and the Maishima plant in Japan. Despite the negative connotations typically associated with such facilities, Hundertwasser’s visionary designs have the power to transform perceptions.

The Maishima Plant, completed in 2001, is a colorful testament to Hundertwasser’s creative genius. Its palace-like structure, adorned with vibrant hues reminiscent of fire and water, embodies the artist’s belief in the uniqueness of natural forms.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Maishima Incineration Plant, 2001, Osaka, Japan.

Featuring an array of windows and columns, each distinct from the next, the Maishima Plant symbolizes technological innovation intertwined with artistic expression and ecological consciousness. Beyond its architectural marvel, the Plant also serves a didactic purpose. It fosters awareness of waste management issues and promotes a more sustainable future.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser: “The house should not be measured by normal standards” (in Hundertwasser architecture: for a more human architecture in harmony with nature, edited by Angelika Taschen), 1997, Köln: Taschen cop., 245-301.

Peter Kraftl: “Living in an artwork: the extraordinary geographies of the Hundertwasser-Haus, Vienna,” (in Cultural Geographie 16), 2009, 119-20: para. 23.

Harry Rand: “Hundertwasse”, 1993, Köln: Benedikt Taschen.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!