5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

If you are taking an introductory art history course in school this semester, you’ll soon be talking a lot about contrapposto. I remember hearing this term constantly when I was a freshman art history student (good times)… So, why not learn all about this key art history concept now?

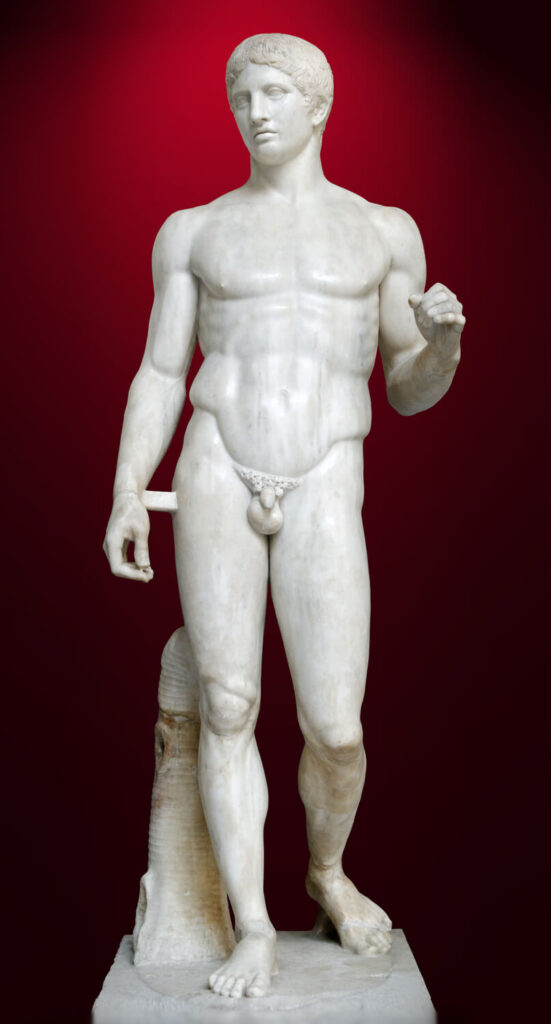

Contrapposto is a dynamic, three-dimensional pose of the human form in which some body parts twist against others. In art, it is closely associated with naturalism, because it reproduces a very natural posture commonly seen in real life.

Contrapposto (Italian, “set against”): A term applied to poses in which one part of a figure turns or twists away from another part. Originally used in the Renaissance to describe certain poses in ancient sculpture, it is now used in a more general sense and also applied to painting, particularly with regard to many Italian 16th-century masters.

– Clarke, Michael. Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. (2nd ed.) pp. 66-67.

The easiest way to understand contrapposto is to experience it yourself. As human beings, we do not typically stand perfectly straight and square to the front. Try it, and you’ll quickly find that it’s neither comfortable nor natural for more than a moment. Next, experiment with finding a more comfortable posture to stand in.

Chances are, you didn’t keep your weight on both feet evenly. Instead, you probably shifted to one foot. (It doesn’t matter which side.) Once you’ve done so, note a few things. First of all, the hip you have your weight on has shifted so it now sticks out to the side. Consequently, the opposite (free) hip has also shifted inward a bit. The more of your weight you move, the more your hips will move as well. Also, there’s now a slight angle to your leg line. Your weight-bearing leg most likely stayed straight – it’s super uncomfortable to bend it in this position – but your free leg probably bent a bit or at least softened.

Lastly, notice where your torso is. It didn’t follow your weight all the way over to your standing leg. Instead, your shoulders probably stayed pretty evenly between your feet, which means that your torso is now slightly angled, and one of your shoulders is a bit higher than the other. If you look in a mirror, you’ll see that your entire posture has several subtle twists and curves, making a sort of S-shape.

Congratulations! You’ve achieved contrapposto. Chances are, this isn’t the first time, but the posture is so instinctual that you’ve likely never noticed it before.

If contrapposto is so easy and natural, why is it a big deal? To understand why it is so significant, check out what sculpture looks like without it.

In the ancient Egyptian statue shown above, none of the three figures stand with contrapposto. While the statue is still pretty awesome, notice how it looks so much stiffer and less dynamic than the other statues on this page. The figures are very square, symmetrical, and frontal. They also lack any sense of movement. The figure of the pharaoh Menkaure (in the center) strides forward with his left leg, but in a way that looks a bit painful. If you try his pose, you’ll find that it’s anatomically impossible. You can’t step forward on two totally straight legs with completely square and level hips. It just doesn’t work, unless your legs are different lengths from each other. That’s probably why he still looks more like he’s standing than moving.

Contrapposto is closely associated with naturalism; therefore, it’s wholly unsurprising to find contrapposto in periods of art history that have strongly emphasized naturalism. Classical Greece is where contrapposto began in western art history, starting around the 5th century BCE. The earlier sculptures of the archaic Greek period, by contrast, do not demonstrate contrapposto. We see strong examples of contrapposto all the way through the art of classical Greece and Rome. It then diminished during the medieval period, though hints of it show up in the willowy, curving forms of some High Gothic sculptures. This is called Gothic sway.

Contrapposto made its resurgence during the Renaissance, particularly in Italy. There, artists rediscovered it in recently excavated classical statuary. We see lots of contrapposto in great Renaissance masterpieces of painting and sculpture. After that, it’s pretty much a standard feature in western art. In fact, it became so ubiquitous that it’s uncommon to hear the term referenced with regards to post-Renaissance works of art. It’s simply taken for granted. For example, John Singer Sargent’s Madame X shows a great use of contrapposto in a late 19th century painting. You may even detect some in the dynamic poses of Picasso‘s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Artists have continued to use contrapposto through to the present day, though some choose to do away with it in order to create an intentionally naive aesthetic.

We tend to talk about contrapposto primarily in association with sculpture, specifically classical statuary. However, the idea equally applies to any other representation of the human figure, including painting and drawing. No matter the medium, creating a believable human body in a constrapposto pose is much more complicated than a square, forward-facing one. It requires perspective, foreshortening, and an understanding of anatomy.

Don’t think that contrapposto is only a European thing! To prove it, here’s a lovely, elegant example of it in a 12th-13th century CE Chinese Bodhisattva statue.

Clarke, Michael. Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. (2nd ed.), p. 66-67.

Davies, Penelope J. E. et al, Janson’s History of Art, The Western Tradition, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2007, p.122-3.

Zucker, Steven and Beth Harris, “Contrapposto explained” in Smarthistory, December 16, 2015. Accessed 31 Aug 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!