The 12th century saw the rise of secular literature centred on heroes. Courtly poetry and prose took up themes of love and chivalry. These stories were the popular culture of the time, Sir Lancelot of the Lake being one of their best loved characters.

Not only have his exploits and love for Guinevere become an inspiration for the generations of writers and poets to come, but medieval artist thrived on them as well. Manuscript illuminations, wall paintings, sculptures, objects of everyday use, the greatest knight of the Round Table was omnipresent.

Scarcely anything is known about Chrétien de Troyes save the fact that he was immensely popular in his lifetime and his influence was profound. Under the generous patronage of Marie of Champagne he turned to writing down the stories well known to French audiences through oral tradition and recast them in the best-sellers of the Middle Ages. What resulted from this work was a new fictional genre: Arthurian romance.

With a chief focus on the marvelous exploits of the knights of the Round Table, Chrétien de Troyes was the first to treat the quest of the Grail and the love of Lancelot and Guinevere. Sir Lancelot of the Lake was to become undisputed star of his romances. Chrétien’s Le Chevalier de la Charette won him international fame spreading from the court of Champagne to the British Isles, Sicily, Scandinavia and Iberian Peninsula, but in search of the real man behind the legend, one should turn to Normandy.

Recent research revealed that in the 6th century (so at the time when historic King Arthur was to rule in Britain) at the abbey of Lessay a knight named Framboldus decided to give up the world and take holy vows. He was to become an abbot, hermit and saint, and Lessay itself popular pilgrims destination. The story of Framboldus served as a basis for numerous oral retellings and for Chrétien’s Chevalier de la Charette. In medieval art one of the most frequently explored motifs of Chrétien’s Lancelot was crossing the Sword Bridge.

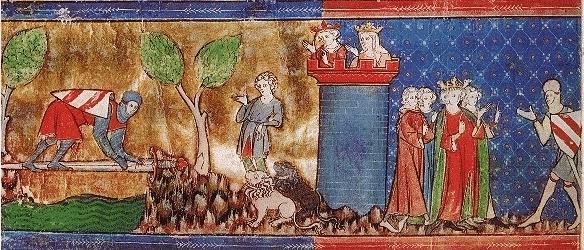

When Guinevere was kidnapped by Meleagant and taken to his father’s realm Lancelot followed to the rescue. However, the only access to the kingdom of Gorre was by the two bridges, one an underwater bridge and even more treacherous Sword Bridge, a steel beam as sharp as a sword and only one foot wide. Lancelot decided to take the perilous Sword Bridge crossing. Having suffered many a wound and bleeding profoundly he reached the other bank. There, locked in the tower, Guinevere awaited to be saved. This part of the story was frequently explored by medieval artists.

First and foremost there is a vast body of illuminated manuscripts with different versions of Lancelot story, one hundred and fifty French alone. One of the most lavishly illuminated is Lancelot dating from around 1315 and created in Northeastern France, most probably Saint-Quentin or Laon. Its pages are filled with lively action and delicate intricate detail. One can only marvel at such exquisite craftsmanship. The Crossing the Sword Bridge scene is one of the most beautiful representations of the theme.

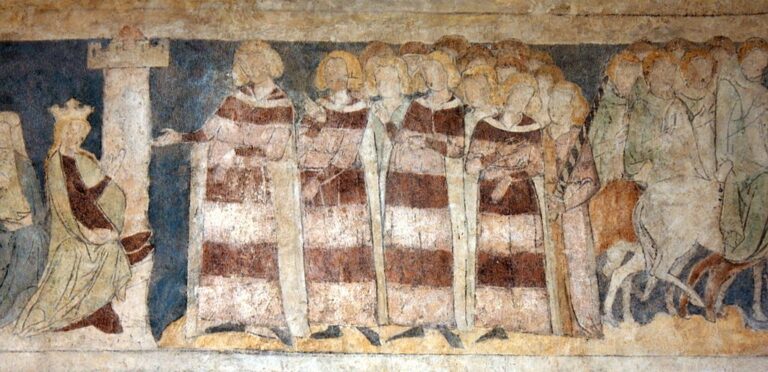

As far as Lancelot wall paintings are concerned there are only two cycles preserved. One in Italy and the other one in Poland. The latter one is a truly remarkable survivor, for it has been preserved in situ, on the very walls of the Great Hall of the tower it was originally painted. The tower’s fabric dates from the early 14th century. Its chief glory comes from the afore-mentioned murals. They were probably commissioned in the 1330s.

Today, being the world’s only Lancelot wall paintings preserved in situ, they rank among the most outstandingly complete and well preserved medieval wall paintings in Europe. The story of Arthur’s greatest knight, his glittering career, adulterous love for Guinevere and subsequent downfall has been told in two registers and should be ”read” from the lower to the upper one, from left to right (as in case of many other examples of medieval cycles). Crossing the Sword Bridge itself has not been shown, but there is Guinevere with her ladies before the walls of Camelot and later carried away by Meleagant. Lancelot rescues the queen in the end, the sinful nature of their love being shown in a depiction where they hold their left hands – a clear symbol of their adulterous affair.

The other Lancelot fresco cycle has survived in Italy. Initially it adorned the walls of a torre, the fortified dwelling in Frugarolo, in Piedmont. But due to the bad shape of the tower itself these frescoes were detached for preservation and put on display in the museum of Alessandria near Turin, thus, unlike the Siedlęcin cycle, has not been preserved in situ. Here fifteen segments illustrated prose Lancelot. They were commissioned in the 1390s by Andreino Trotti, ardent supporter and confidant of Gian Galeazzo Visconti. Trotti who won his fame in service to Spain helping to stop a French invasion. The wall decoration was created by an anonymous painter known today as The Master of Andreino Trotti.

Curiously enough, in one of the retelings of Lancelot legend Lancelot himself overcome by longing and grief during his captivity in Morgan le Fay’s castle, turned to painting his story on the walls of his chamber, thus becoming an author of the first cycle of wall paintings treating his own subject matter. King Arthur discovered these frescoes being the definitive proof of Lancelot and Guinevere’s guilt.

Scenes derived from Lancelot romances were also used to decorate objects of everyday use: mirror frames, combs and caskets. Beautifully adorned ivory caskets would have belonged to a lady of noble birth: a queen, a princess, a duchess. Sometimes even a wife of a wealthy merchant would have called herself a happy owner, too. They showed the figures of both ancient and medieval pedigree: Tristan and Iseult with King Mark spying on them from a tree, Gawain on a Perilous Bed and, first and foremost, Lancelot, crossing the Sword Bridge and fighting the lions. They began to flourish in Paris in the first half of the 14th century and were used for keeping jewelry and other valuables. Today there are only seven such caskets preserved in museums all over the world.

The 19th century saw a revival of Arthurian literature and art brought about by the Victorian poets and members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who in their reforming, almost missionary zeal turned to the long forgotten heroes of the Middle Ages, Sir Lancelot of the Lake among them. What resulted from their work were the best loved poems, such as the Idylls of the King, paintings by Edward Burne-Jones and Holy Grail tapestries by William Morris. The latter ones are a true marvel to behold. Even today Lancelot’s fame echoes in the films and songs, most famously in Loreena McKennitt’s hauntingly beautiful musical version of Tennyson’s Lady of Shalott.

Katarzyna Ogrodnik-Fujcik