The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

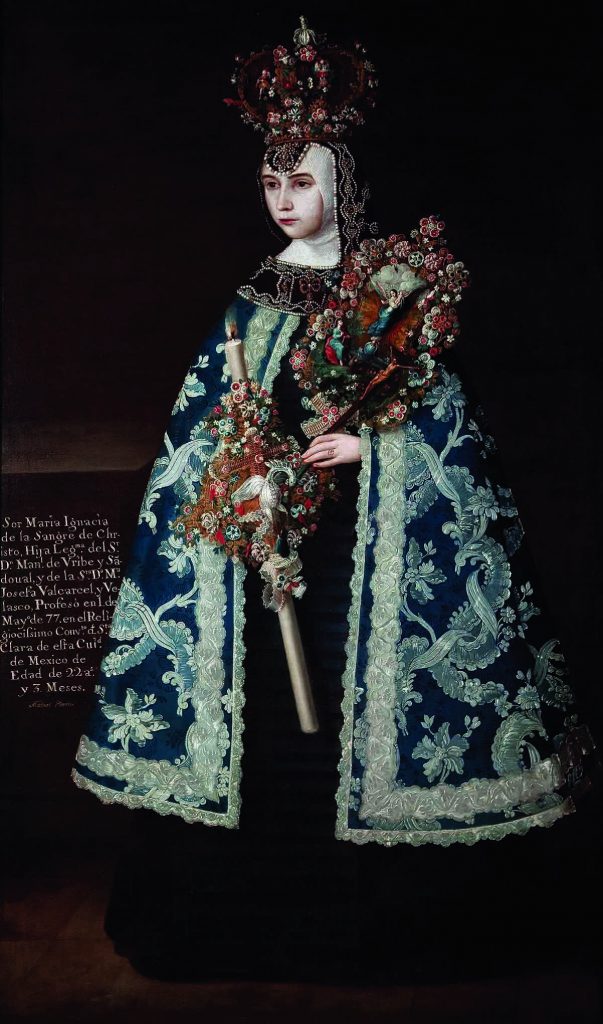

Gambol into the lobby of most Mexican hotels, or visit any antique store in Mexico, and you’re bound to find a portrait of an 18th or 19th-century nun wearing a crown of flowers. Who is she? What does she represent? Is she relevant beyond an old-timey subcategory of portraiture?

The crowned nuns, named for the intricate floral crowns atop their heads, are often accompanied by baby Jesus or objects such as candles or lots of flowers. These lavish portraits were made on the occasion when a nun officially entered a cloistered convent.

In colonial Mexico, nuns were understood to be integral to the health of a community, since they prayed on behalf of people to help shorten one’s time in purgatory. Nuns lived cloistered in a convent, meaning that, once they entered, they did not leave and were considered dead to the secular world. The only exception was leaving to create a new convent in another city.

Nuns became increasingly important in the 17th and 18th centuries with the rise in silver production. The silver economy meant more families acquired wealth, allowing them to pay the dowry needed to permit their daughters’ entry into a convent. A marriage dowry was more expensive than one needed for a convent, so becoming a nun was often a nice alternative for wealthy women. While nuns might never see their families again, many could live a life of comfort inside the convent.

The infant Jesus in most crowned nun portraits often represented the babies the nun would not have. Later, after her death, the baby Jesus was often returned to her family, becoming part of the nativity set. A nativity set with multiple baby Jesus images represents a family tree with many nuns. Portraits of crowned nuns were commissioned by a nun’s family as a last act of vanity before joining the convent. The clothing and flowers were costly and a portrait like this indicated a family’s wealth.

Though Indigenous women weren’t allowed to become nuns until 1724, they were always present in the convent as servants, and it was likely these women taught the Creole and Spanish nuns the Mesoamerican art of making flowers garlands and crowns. Ancient codices featured Aztec goddesses wearing flower crowns and included details on how to make them. Nuns’ portraits weren’t captured again, until after their death.

Crowned portraits also functioned as official documents recounting the nun’s lineage, including her parents’ names and when she entered the order. The portraits expressed the popular opinion that Mexico was the site of the new garden of paradise, whose most precious flowers were its nuns. This also provided a sense of solidarity among Mexico’s nuns regardless of order or ethnicity.

Crowned nun portraits are exclusive to Mexico. In Spain, only nuns who were an abbess, or convent’s founder, were memorialized in a painting. Keep in mind that, at the time, women did not have the right to free speech or the right to vote in Mexico, or anyplace else in the world.

Today, the largest collection of crowned nun portraits is owned by the Banamex bank.

Author’s bio:

Joseph Toone is San Miguel de Allende’s expert on the Indigenous and Spanish roots of our modern traditions. Toone is Amazon’s bestselling author of the San Miguel de Allende Secrets books series and TripAdvisor’s top-ranked tour guide explaining why San Miguel de Allende is truly the heart of Mexico. Toone is also the creator of the Mexican Maria Doll Coloring Book promoting Indigenous female artists and speaks internationally on the Power of Feminine in central Mexico. For more information visit his website.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!