Marian Henel—Tapestries and Madness

Marian Henel’s tapestries are huge. The largest one measures over 6 m in length and 3 m in width (19 ft. 8 in. by 9 ft. 10 in.). Created in the...

Zuzanna Stańska 25 November 2024

With its maze of narrow streets, bridges, and canals linking its splendid architecture and art, Venice is beautiful. It is worth exploring and a wrong turn can be thrilling. Even the elephant was so curious that it went to church! What other stories does the city have for us to uncover?

Venice has always fascinated travelers. Even today people are ready to absorb the splendor of the palazzi and the churches, the picturesque canals, the bridges, and the campi. Venetians also celebrated their events with grandeur, attracting visitors. Many artists used any opportunity to depict Venetian festivities. One of these artists was Francesco Guardi (1712–1793). He lived in the city his entire life and focused on veduta or highly detailed, usually large-scale cityscape paintings. For example, he painted the celebration of the Doge’s annual ritual marriage to the sea.

We can see the barge of the Doge, Il Bucintoro, sailing with its stem pointed towards the Riva degli Schiavoni. The façade of the Doge’s Palace and the bell tower of St. Mark’s Church serve as points of reference. The teeming gondolas accompany the illustrious party. Due to its small dotting and spirited brush strokes, Guardi’s style became known as pittura di tocco.

Depicting another side of Venice, Pietro Longhi (ca. 1701–1785) picked out scenes from daily life by creating the stories for us. In his paintings, we can find rhinoceros, monkeys, mice, and elephants. For example, here he shows a crowd staring openly at a bizarre Indian rhinoceros.

During carnivals, curiosities of various kinds appeared one after another in St. Mark’s Square: puppeteers, magicians, astrologers, and charlatans. Exotic animals, such as lions or rhinoceros, were among the main attractions. In 1751, during the carnival, Douwe Mout van der Meer, a captain of the Dutch Indies company, brought an Indian rhinoceros named Clara to Venice. We can see how Pietro Longhi’s painting Il Rinoceronte magically connects two different aspects of life, placing the animal in the fascinating atmosphere of the Venetian carnival.

It seems that Venice has always managed to come up with ideas for amusement. During another carnival of 1818-1819, the locals brought an elephant and kept it in the Riva degli Schiavoni. The elephant, whom we call Jacopo, could not imagine that his role was to delight the royal guests, Francis I, Emperor of Austria, and his wife. It was the carnival and he probably wanted to entertain himself.

As a part of the celebration, the Venetians fired an artillery salute that was so strong that it damaged the facades of some houses. Then matters got worse when Jacopo, provoked by the sound of artillery, became uncontrollable. Thus the locals decided to send him away from Venice. For this purpose, they brought in an enormous boat and encouraged the elephant to walk on board. However, the water was rough and the plank was unsteady. After having tried to board four times, Jacopo finally gave up and refused to continue. Subsequently, his custodian confined him to a storeroom.

Jacopo did not like his confinement. He was not able to see all these beautiful places in Venice! Who would not be angry in such circumstances? Thus, our elephant broke loose and ran towards a bridge.

Oh, no, I have to cross the bridge! No way I could make it.

Jacopo’s after-escape thoughts.

The elephant shook his head, trumpeting. Not liking the idea of having to take another step, he turned around. Crossing a bridge often requires courage, but it is not always scary. Little did he know some Italian painters, such as Michele Marieschi (1710–1744) liked to transform urban cityscapes by exaggerating the view. For example, here we can see the Rialto Bridge with its stalls and the embankments nearby. This area was the trading and business center of 18th-century Venice.

However, in the past Venice did not have any bridges. People moved from one island to another by their own boats or using the ferries of the time. The situation changed in the middle of the 13th century when Venetians started to connect the islands to one another. Initially, the walkways were wooden and later bridges replaced these structures. Only in the 19th century did they add guardrails due to an increase in people falling into the water. Today, the city has more than 400 bridges.

Jacopo the elephant then briefly stopped at a stall to eat fruit and drink coffee. He went toward Calle del Dose, across Campo della Bragora, and up Salizada Sant’Antonin. Running toward the bridge, he realized again that bridges were not for him. Instead, he broke into a nearby church. All this time, soldiers had been firing their rifles at his bulletproof, thick skin.

The Venetians were trying to decide what to do with the elephant. Meanwhile, Jacopo moved benches around to build himself a kind of fortress in front of the main altar. In the process he shattered one of the tombstones on the floor of the church, trapping his foot. The authorities brought a cannon and bored a hole in the sidewall of the church. They fired two shots, killing Jacopo. After the event, they sent his body to the deconsecrated church of San Biasio. From there they sold the elephant to the Natural History Museum in Padua.

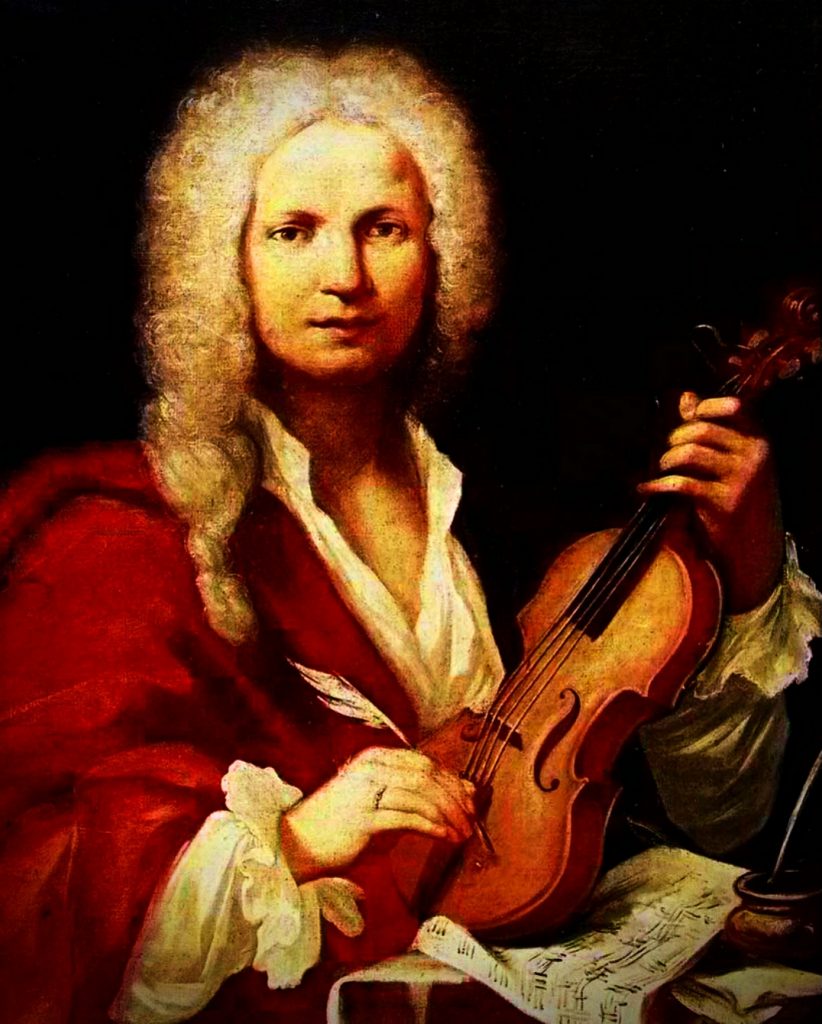

It is a pity that the red priest was not around at that time. His music might have entertained Jacopo on his last journey. Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741), the red priest, was born in Venice in the parish of San Giovanni in Bragora, only a ten-minute walk from Saint Mark’s Square. However, at that time it was a fairly unfashionable part of Venice. Vivaldi got his nickname, the red priest, because of his fiery red hair. His father was Giovanni Battista, a violinist, also known as the redhead.

It is interesting that in this probable portrait of Vivaldi, the artist does not show the composer as a priest. Vivaldi is wearing a fashionable and slightly informal dress and a wig. However, Pope Innocent XIII would soon ban the wearing of wigs by priests.

Vivaldi began studying to become a priest when he was 15 years old. By the age of 25, Vivaldi was an ordained priest. This role had not been easy for him though. From his childhood he had suffered most likely from asthma. Therefore, while training for the priesthood Vivaldi remained at home with his parents. Because of his illness, he had to leave the alter without completing the mass on several occasions. However, some suspect that he probably rushed away from the alter to jot down his musical notes.

Vivaldi was able to combine his passion for music with the priesthood. He became a violin teacher at the Ospedalle della Pietà, which was a convent, orphanage, and music school in Venice. It was not long before Vivaldi began to organize young ladies into small chamber orchestras. They would become famous throughout the city, attracting visitors from all over Europe.

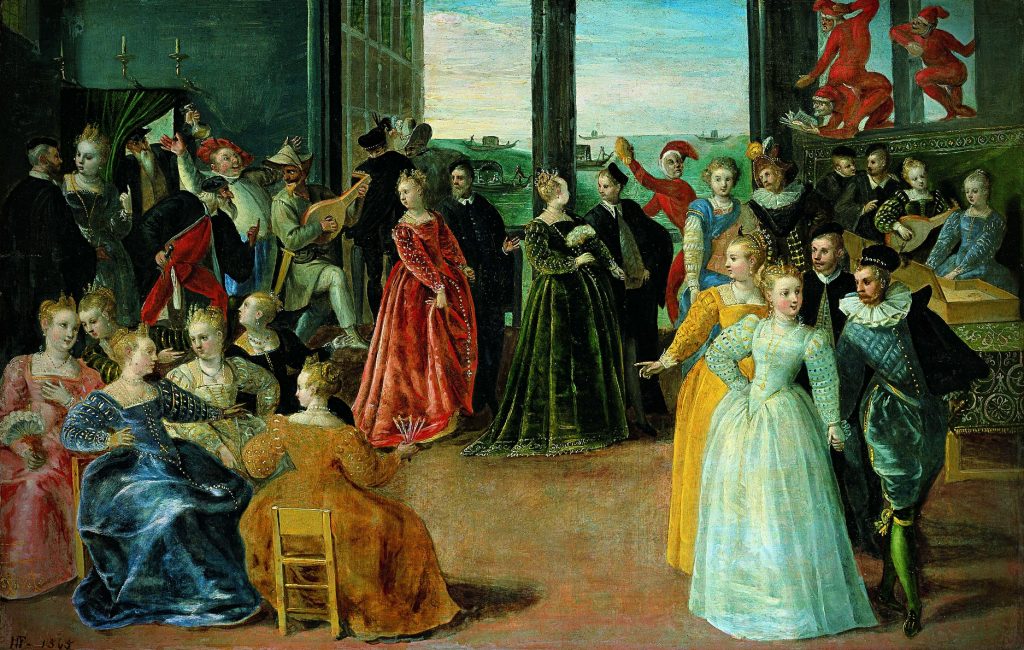

During the 18th century, Venice reached its apogee as the pleasure capital of Europe. Here Francesco Guardi shows a celebration organized in honor of the Russian Counts who visited Venice in 1782. Among the multitude of people, we can see the orphan girls from the Pietà.

Perhaps the guests could listen to Vivaldi’s music all year round. One of his famous violin concerti is the Four Seasons. This music does more than express the physical world: the buzzing of flies or the barking of dogs. It conveys the spirit of the seasons, heavy summer or the trembling arrival of spring. This musical work is one of the earliest examples of program music or music with a narrative element. We can conjure up the return of spring and the festive songs of birds.

Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar,

casting their dark mantle over heaven.

Then they die away to silence,

and the birds take up their charming songs once more.Vivaldi, Sonnet Four Seasons. Translated by Armand D’Angour.

At some point, Vivaldi became restless in Venice and began a series of journeys. But who accompanied him? First, it was a young contralto singer, Anna Giro, once one of his pupils. Vivaldi also included her beautiful younger sister, Paulina, as part of his entourage.

As Vivaldi and his operas became increasingly popular, curious fans wanted to know more about his private affairs. When the public was not certain of something, they began to gossip. Over time, stories about the red priest circulated widely. However, Vivaldi himself wrote very few letters to set things right.

The mandolin enjoyed popularity in the 18th century and Vivaldi composed for the instrument. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), a painter from Venice, depicted a woman holding a mandolin, listening to the pitch of the note as she adjusts the strings. Her luminous skin serves to heighten the sensuous poetry of the painting. She represents the ideal of feminine beauty.

Anna Girò was 17 and Vivaldi was 48 when she became his protégée. He taught her some singing techniques relevant to his operas. Vivaldi even highlighted her talent with a unique aria. However, critics noted that his pupil performed miracles, even if her voice was not one of the most beautiful. Many critics of the time agreed that Anna had a great talent for acting but that her voice was not strong.

Nevertheless, Vivaldi continued to feature her in his operas for the next 23 years. Since his operas were performed in multiple cities, Anna traveled with him from venue to venue. Her sister Paolina joined the entourage as well. Not only did rumors circulate that Vivaldi was having a love affair with Anna, but some people thought he was also romantically involved with Paolina. When they arrived in Ferrara in 1737, the clerical authorities even tried to ban them from appearing. Given his devotion to the Church, these rumors are unlikely to have been true. However, Vivaldi’s protective behavior towards Anna only intensified them.

While Vivaldi was traveling, styles and fashions were changing quickly in Venice. The poet and playwright Carlo Goldoni was bringing a breath of realism to the stage. Venetian audiences loved commedia dell’arte with its Harlequin and Columbine because they were funny, irreverent, and wicked. Since these shows had their musical accompaniments, Vivaldi’s music was going out of fashion.

Moreover, Vivaldi was abroad for so long that his association with the Pietà came to an end. He went to Vienna hoping that his old patron, the emperor Charles VI, would support him. However, his patron died and Vivaldi’s hopes were shattered. He lived in poverty and fought a losing battle with his failing health. He died in Vienna and his funeral service was held in the cathedral of Saint Stephens. The Altar with Pietà in San Giovanni in Bragora reminds us of Vivaldi because he was baptized there in 1678.

Like Pietro Longhi, Vivaldi captured the rhythm and energy of the city. Still, the elaborate music of the Baroque period began to evolve into more elegant music. It would become the hallmark of the classical period, and composers like Vivaldi were forgotten. Had Vivaldi been born ten or twenty years later he might have been a leader in this musical revolution. Instead, his work was old-fashioned even before his death. Many years would pass before music lovers began looking back to Vivaldi’s time. They found his music vibrant, surging with life and energy, passionate, and compelling.

We know Venice for its beauty and excess, but both can be dangerous. Venetians and visitors still took risks and wore carnival masks that gave them anonymity. Consequently, many were able to seek the company of the prostitutes of Venice, whose fame was a great tourist attraction. Nevertheless, the authorities tried to limit the sex workers to Castelletto, which is not far from Rialto. Venetian streetwalkers congregated on one particular bridge which became known as the “Bridge of Breasts.”

The city of merchants loved numbers. So in 1509, they counted more than 11,000 sex workers in a city of about 100,000 people. The working girls of Venice fell into different categories. They were either cortigiana di lume (lower-class workers) or cortigiana onesta (meaning “honest courtesans”). This definition would apply to any woman having intercourse outside of marriage, or even receiving gifts from a man.

The laws governing their behavior were strict. For example, they could not live on the Grand Canal or travel in a boat with more than two oars. Sex workers also had to wear a yellow scarf and the law also prohibited them from attending church on feast days. However, some women managed to find a loophole. In 1543, a woman accused of unlawfully attending church said she was a “married courtesan” and thus escaped punishment.

These working girls were also not permitted to wear jewels, silk, or gold as lavish dress could be viewed as assertive, calling attention to individual identity and showing the autonomous possession of wealth. Furthermore, the authorities were concerned that tourists would confuse the well-to-do courtesans with wealthy women.

Despite these restrictions, some women climbed up the ladder of success and became courtesans. Among these was the famous Veronica Franco, born in Venice around 1546. She was educated by private tutors in her family home and while still in her teens she married a physician. However, it was probably an arranged marriage and ended shortly thereafter. Franco was forced to support herself and became an “honest courtesan.”

Franco was a woman of great talent, charm, and beauty. She continued her education by visiting literary gatherings of writers and painters in Venice during the 1570s and 1580s, conversing with politicians, poets, artists, and thinkers. She became so famous that the government hired her to “entertain” Henry III of France when he visited Italy in 1574. Subsequently, she published a book of poetry and a collection of her letters, which included her correspondence with King Henry III.

For many courtesans, things were not always so straightforward. Some believe that when she was 40 Franco decided to change her way of life. She helped to establish a House of Help near Carmine. It was a house of refuge for prostitutes who wanted to change their lives. Subsequently, some of them married, others took religious vows, and some returned to their families. Before her death in 1580, Franco wrote to a mother who wanted her daughter to become a prostitute. She replied: “It is so unhappy and against the sense of humanity to oblige the body to such servitude that the mere thought is terrifying.”

Venice is a city where many paths and destinies can cross. At first glance, many would think that Antonio Foscarini (ca. 1570–1622) was lucky. He belonged to the Venetian nobility, had considerable wealth, and successfully began his career. He was a Venetian ambassador to both the courts of King Henry IV of France and James I of England. However, in 1615 he was called back to Venice because his secretary had accused him of treason with Spain. While the charge was being examined, Foscarini remained in prison for three years.

Finally, it was determined that he was not guilty. He was released from prison and restored to his seat in the Senate. Here the story would end, but several years later two inquisitors again accused Foscarini of treason with Spain, Venice’s enemy at that time. They arrested, imprisoned, condemned, and strangled him. They ordered him to be hung by one foot between the columns of San Marco and San Teodoro.

Several months later the city council determined that Foscarini was not guilty, admitting that the verdict was a mistake. His denouncers were convicted of false accusations. However, before they could give any explanation, the council ordered the hanging of the accusers. Nevertheless, for Foscarini, it was too late. Some people attributed the cause of his death to various religious and political forces prevalent in Europe at the time.

Other people offered a simpler explanation: Foscarini has failed to defend himself. But what could be the reason? The palazzo, where he supposedly passed state secrets to his Spanish agents, was also the home of the Countess of Arundel, wife of Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel. He held a high position at the English court and therefore would likely meet with Foscarini in London.

It was believed that Foscarini was in the house of foreigners “in disguise and normal dress”. However, in Venice, a city famous for its carnivals and disguises, would not a lover sometimes wear a mask to visit his mistress? The Countess of Arundel vehemently denied the story. Thus a cloud of the unknown covers this story. Foscarini was falsely accused and they either did not give him a chance to defend himself or he chose not to. Consequently, he died and his supposed lover, married to an earl, denied the affair.

Francesco Hayez (1791–1882), an Italian artist, painted his Valenza Gradenigo before the Inquisition based on the fictionalized story of Antonio Foscarini. Valenza Gradenigo, guilty of having attempted to save the man she loved, Antonio Foscarini, appears before the Venice Inquisitors. They include her father depicted in the center of the room.

Francesco Hayez shows the drama of the scene, emphasizing the theatricality of the trial. He reveals to us a silent dialogue of glances and expressions exchanged between the characters. The woman could not take the trial and appears lifeless. By contrast, the father has a stern composure, supported by the scornful expression of the young judge.

Venice is a place full of words, histories, and memories, and it has always captivated travelers. They admire the splendor of its palaces and churches and the strikingly picturesque canals. Visual artists like Guardi, Longhi, and Canaletto, or musicians like Vivaldi, were inspired by the city’s landscape and its changing palette. They created stories that help us discover the city’s fascinating past.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!