Today is a special date. Exactly 8 years ago, in 2012, everything began for us with the launch of the DailyArt mobile app. It is a very simple app – every day it presents one piece of fine art with a short story about it. The app is currently available in 16 languages and this year will be available in two new ones (Dutch and Greek). If you’re not familiar with it yet, you can join our community of 1 million art lovers and download it for free from App Store and GooglePlay. Here’s a little taste, the best paintings presented in DailyArt app in 2020!

Since 2012 DailyArt grew. We launched DailyArt Magazine, which you are reading now, every year we sell physical calendars (we are preparing the ones for 2021, stay tuned!) and we have just launched our new initiative, DailyArt Courses, with art history courses. Check it out!

We want to thank you for being with us all this time, for all your support and patience. As a small thank you gift, today the PRO version of DailyArt (without ads and with unlimited access to our Archive, Search and Favs) will cost $1.99 instead of $5.99. So once again, if you’re interested, download the app from App Store or GooglePlay and tap “Upgrade to PRO” button 🙂

Also, on this occasion we want to share with you our 10 most liked DailyArt posts published in the app this year. Our best of the best of this unexpected 2020. 🙂 Have fun!

1. Carl Friedrich Seiffert, The Blue Grotto in Capri

Our number one of this year is a very calm and beautiful example of German Romanticism. “They all dreamed of this grotto and, truly, the reward for their discovery could only be revealed through painters and poets from the distant time of those who searched for the wonderful poetic blue flower among the undines in the depths,” as Ferdinand Gregorovius remarked in 1880 looking back at the romantic vision.

Already known in ancient times, the Blue Grotto on Capri was thought to be a place inhabited by demons. The young painter August Kopisch, who came to Capri in August 1826, was not deterred by this superstition. Together with his friend Ernst Fries, he discovered the grotto with its fairytale-like play of light and colors. On August 17, 1826, he wrote in the guest book of the hotelier Pagano: “We named it the Blue Grotto (la grotta azzura) because the light from the depths of the sea lights up its whole vast blue space. Visitors are overcome to see the blue fire-like light filtering through the water in the grotto, each wave appearing like a separate flame”. The artists drew and painted the grotto; Kopisch described and published his experiences several times. Since its rediscovery, the Blue Grotto has become one of the main tourist attractions on the island. Numerous painters chose this natural spectacle as the subject of their works, including Carl Friedrich Seiffert, who increasingly turned to southern landscape motifs after his trip to Italy.

2. James Tissot, Passing the Storm

James Tissot was a 19th century French painter who spent much of his life in Britain. You must forgive me but recently I became obsessed with his works! 🙂 So here we are, a perfect painting for our current situation. Or a painting that is a perfect reminder for our current situation—that all the storms, even the worst ones, pass (the piece was published on May 16th, and of course we meant COVID-19).

Though never really an Impressionist (his brushwork and drawing ability were too precise for that categorization), Tissot had many ties to the Impressionist community. He was a friend of many of them and in 1874, Degas asked him to join them in the first exhibition organized by the Impressionists, but he refused.

Passing the Storm was painted around 1876. If you take a closer look at it, you will see that in the background, storm clouds gather while in the foreground, young lovers have obviously just quarreled. The man in the painting stands on the terrace separated from his lover, brooding. The woman lies inside on the divan and her body assumes the attitude of one who has recently been upset. We can’t know that for sure, but I have a feeling that after this storm (and a quarrel) a beautiful sun showed up.

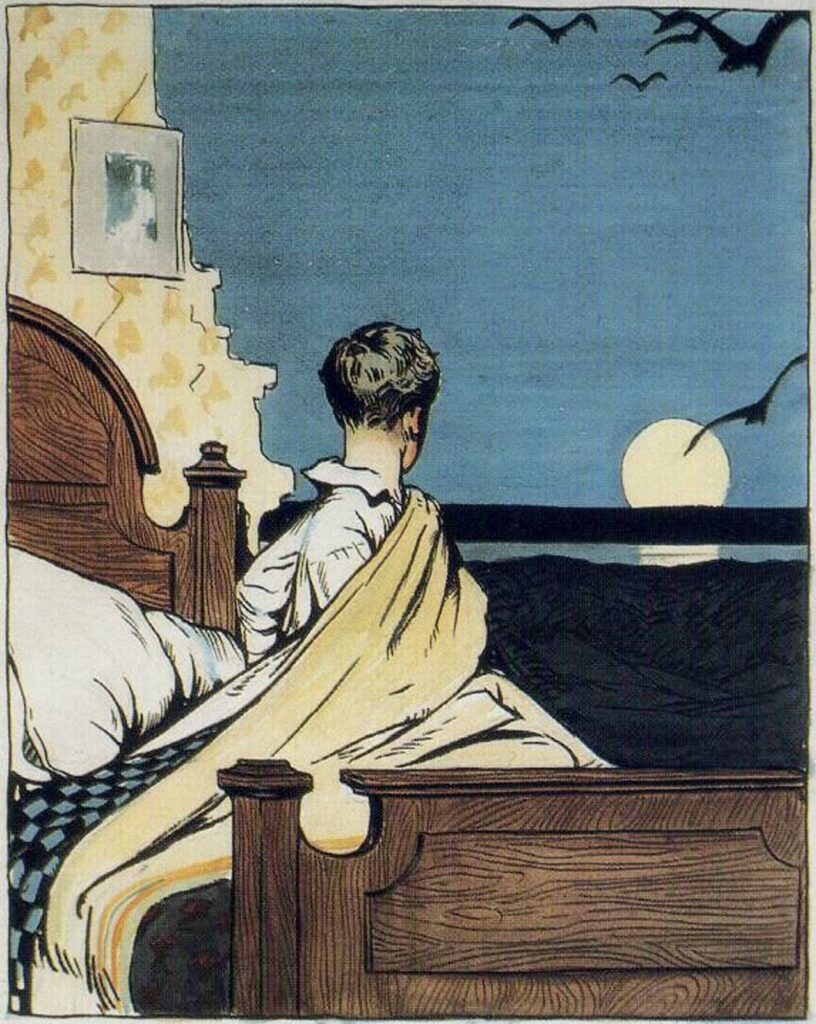

3. Edward Hopper, Boy and Moon

There are so many widely unknown masterpieces of Hopper that I’m usually shocked when I discover things like today’s drawing. It looks totally non-Hopperish. The 1906 painting is the earliest among Hopper’s works at the Whitney Museum. Hopper was around 24 years old when he made the drawing and was just on his way to his characteristic style. A year before, Hopper began working as an illustrator for a New York City advertising agency but never really liked illustrating and longed for the freedom to paint from his imagination. Unfortunately, success was slow in coming and he was forced to earn his living as an illustrator for nearly 20 more years until his painting career took off.

4. Zdzisław Beksiński, Untitled

Beksiński was a Polish artist who created his works out of a sense of fear, loneliness, and a strong conviction about the nothingness of life and the power of death. His painting is characterized by very careful workmanship. He presented scenes existing somewhere on the verge of reality. The artist was not interested in objects as they appear in reality, but transformed only for the use of art, which, in his opinion, does not consist in reflecting nature but in presenting visions. Beksiński’s works show the world as we see it in a dream—in dreams, however, this transformed world appears to us as natural.

It is not entirely right to identify Beksiński’s style with Surrealism. The method of free associations connected it with this movement, but the artist himself felt the strongest connection with the painting of the 19th century. Do you also associate this picture with the Rouen Cathedral series by Monet?

Unlike the Surrealists, Beksiński did not have a strict artistic program and his paintings did not completely transform reality. The process of their creation can be divided into “photographing” the visions that the artist experienced and then painting the rest of the scene.

The work presented today comes from the 1980s. In that period, the artist painted pictures in which the significance was not as important as in his earlier works. He himself emphasized that searching for a hidden meaning in his visions made no sense, one must simply absorb this world without trying to explain it rationally.

5. Gustav Klimt, The Kiss

The Kiss, probably the most popular work by Gustav Klimt, was first exhibited in Vienna in 1908 at the Kunstschau art exhibition on the site of today’s Konzerthaus. The Ministry then bought it for the sum of 25,000 Kronen and thus secured for the state one of the icons of Viennese Jugendstil and indeed of European modern art.

The Kiss undoubtedly represents the culmination of the Golden Epoch phase in Klimt’s art. In this decade, the artist created a puzzling, ornamental encoded program that revolved around the mystery of existence, love, and fulfillment through art. Klimt gained initial inspiration for this piece in 1903 on a journey to Ravenna to see the Byzantine mosaics. In addition, the painting contains a myriad of motifs from various cultural epochs, above all from Ancient Egyptian mythology. Most recent research, however, has revealed that it is not enough to read the ornaments in the picture merely as symbols rooted in tradition, aiming to convey a timelessly valid message. They reveal more, such as references to Klimt’s love for Emilie Flöge and the artist’s exploration of the sculptor Auguste Rodin’s art.

It is no coincidence that Klimt’s work is often linked to that of his Viennese compatriot and near-contemporary, Sigmund Freud. When Klimt died in 1918 at the premature age of 55, several unfinished works of a strikingly sexual nature were found in his studio, as if revealing the erotic undercurrent latent beneath much of his earlier work.

It was a perfect Valentine’s Day painting, wasn’t it?

6. Claude Monet, The Water-Lily Pond

In 1883 Monet moved to Giverny where he lived until his death. There, on the grounds of his property, he created a water garden “for the purpose of cultivating aquatic plants,” over which he built an arched bridge in the Japanese style. In 1899, once the garden had matured, the painter undertook 17 views of the motif under differing light conditions. Surrounded by luxuriant foliage, the bridge is seen here from the pond itself, among an artful arrangement of reeds and willow leaves.

In a letter, Monet described how he had planted the water lilies for fun. He never intended to paint them however, once they established themselves, they almost became his only source of inspiration. He wrote: “I saw, all of a sudden, that my pond had become enchanted… Since then, I have had no other model.”

7. Vincent van Gogh, Irises

Van Gogh painted this still life in the psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy. For him, the painting was mainly a study in color. He set out to achieve a powerful color contrast. By placing the purple flowers against a yellow background he made the decorative forms stand out even more strongly. The irises were originally purple but as the red pigment faded they turned blue. Van Gogh made two paintings of this bouquet. In the other still life, he contrasted purple and pink with green.

8. Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers

Van Gogh’s paintings of sunflowers are among his most famous. He did them in Arles, in the south of France, in 1888 and 1889. Vincent painted a total of five large canvases with sunflowers in a vase with three shades of yellow “and nothing else.” In this way, he demonstrated that it was possible to create an image with numerous variations of a single color, without any loss of elegance.

The sunflower paintings had a special significance for Van Gogh – they communicated “gratitude,” he wrote. He hung the first two in the room of his friend, the painter Paul Gauguin, who came to live with him for a while in the Yellow House. Gauguin was impressed by the sunflowers, which he thought were “completely Vincent”. Van Gogh had already painted a new version during his friend’s stay and Gauguin later asked for one as a gift, which Vincent was reluctant to give him. He later produced two loose copies as well, one of which is now in the Van Gogh Museum.

9. Edward Hopper, Cape Cod Evening

Edward Hopper painted Cape Cod Evening in 1939 in Truro, a small fishing village on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. The artist stated: “It is no transcription of a place, but pieced together from sketches and mental impressions of things in the vicinity. […] The dry, blowing grass can be seen from my studio window in the late summer or autumn. In the woman I attempted to get the broad, strong-jawed face and blond hair of a Finnish type of which there are many on the Cape. The man is a dark-haired Yankee. The dog is listening to something, probably a whippoorwill [sic] or some evening sound.” According to his wife, the painting was originally to have been titled Whippoorwill, after the nocturnal bird known for its distinctive song.

Several aspects of the scene are disturbing: typical of the human protagonists of Hopper’s paintings, the man and woman—presumably a couple—are self-absorbed and oblivious to each other’s presence; the uncut grass and encroaching locust grove are out of character with the well-maintained house; the dog’s alert stance seems a portent of some imminent danger; and the advancing darkness of evening imparts a melancholy mood. In Cape Cod Evening, Hopper presents an assemblage of carefully orchestrated dissonances that convey a generally pessimistic, skeptical attitude toward human identity and humanity’s relationship with nature.

10. Jean-Léon Gérôme, Truth Coming Out of Her Well

This is the painting which closes our Top 10 of 2020. And I know, it is a bit werid 😀 Beginning in the mid1890s, in the last decade of his life, Gérôme made at least four paintings personifying Truth as a nude woman, either thrown into, at the bottom of, or emerging from a well. The imagery arises from a translation of an aphorism of the philosopher Democritus, “Of truth we know nothing, for truth is in a well.” The nudity of the model may arise from the expression, la vérité nue, the naked truth.

It has been assumed that the painting was a comment on the Dreyfus affair, but some art historians argue that Gérôme’s images of Truth and the well were part of his ongoing diatribe against Impressionism, which is kind of funny.

The multiple interpretations of the painting’s enigmatic meaning prompted one of the museum’s curators to say, “This is our Mona Lisa.”

Thank you for being with us! Now that you’ve discovered the top paintings in the DailyArt app, do you want to meet the team behind the magazine?