Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix is a thought-provoking exhibit on many levels. Quietly on display on the second floor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from July 17, 2018, until November 12, 2018, I was able to see sides of Eugène Delacroix that I had not been exposed to before.

The sketchbooks and other drawings in this exhibit were not meant to stand on their own as works of art. They were meant to be a means to an end. The drawings were successful when the paintings that emerged from them were successful. Yet I could not help but view these drawings as works of art in their own right. I am not bound by the intentions of the artist who creates the artwork. The artist’s intentions are merely a starting point for me.

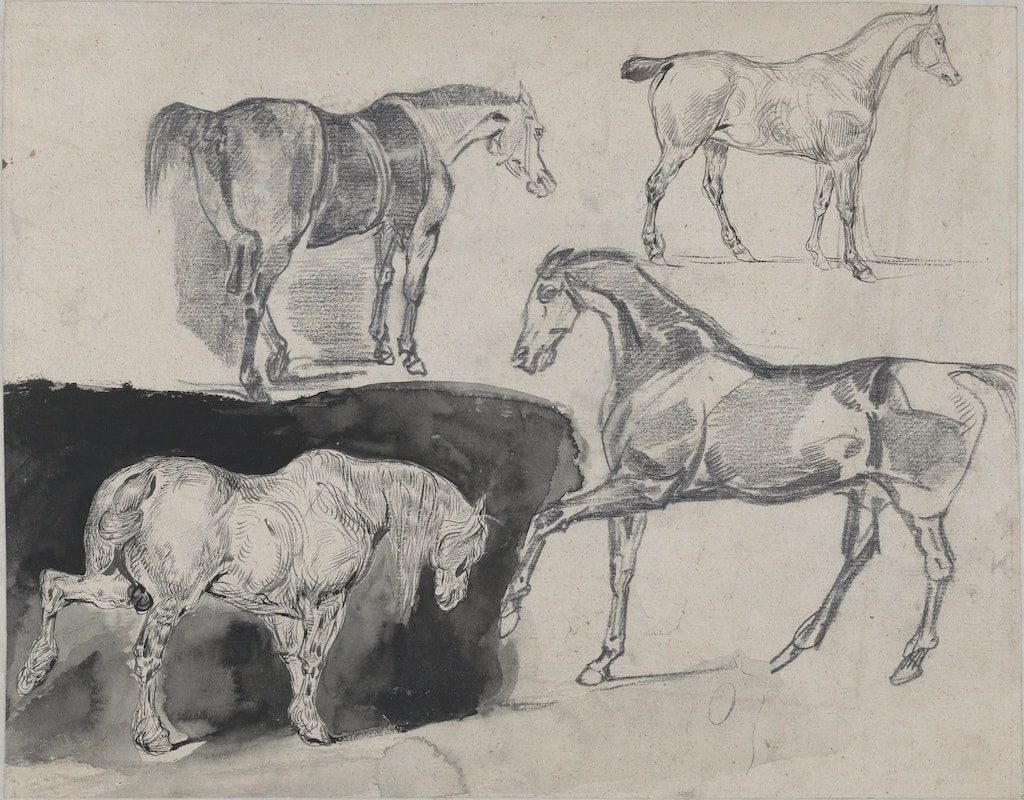

The sketchbooks also reveal Delacroix to be a dedicated student of his craft. He drew horses to learn how to draw horses better. He drew the human figure for the same reason, and his approach to drawing the figure was as instructive in its own way as a George Bridgman anatomy drawing would be from one of his anatomy books.

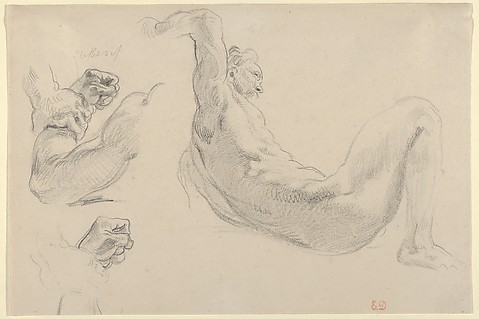

One of my favorite drawings in the exhibit was a graphite drawing: Studies of a Fallen Male Nude for “Hercules and the Horses of Diomedes.” The reclining male figure, with his bent arm raised over his head, has taught me a lot about fine draughtsmanship—the way the figure is clearly divided into light and shadow by having a clear terminator line, especially in the torso. (The terminator is a line, or rather a series of lines, in the same way, the contour of the figure is made up of lines. The job of the terminator is to separate light from shadow, and many argue that the terminator is more important than the contour line on the shadow side of a form.) The bones and muscles are clearly drawn as well. We can clearly see the scapula, from which the deltoid muscle grows upward on the left side of the right arm, opposed by the curve of the triceps on the right side, with the box-like form of the elbow (or olecranon) above it.

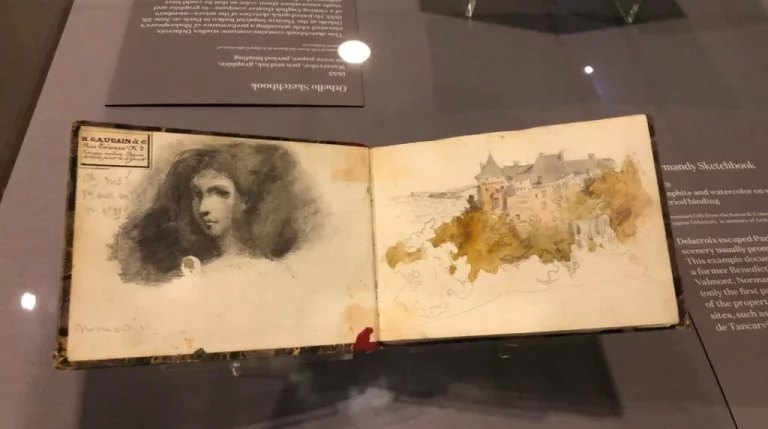

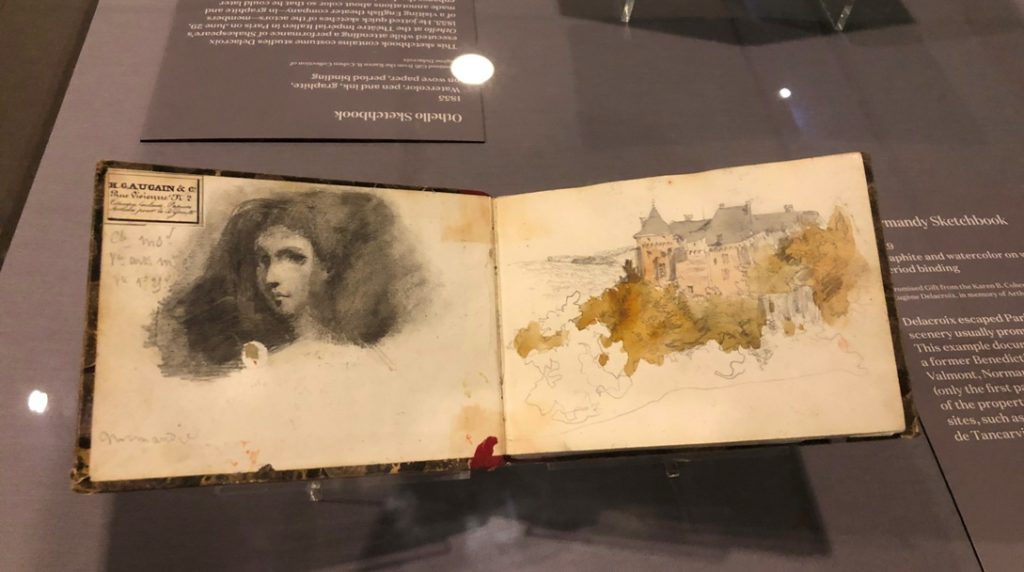

The sketchbook, when approached in a healthy way, can be a place for an artist to be alone, to explore and to experiment in the privacy of his own mind, much like someone who is making entries into a diary. These drawings were not meant to be shown to thousands and thousands of visitors in a museum; they were meant to be observed and studied by the artist himself.

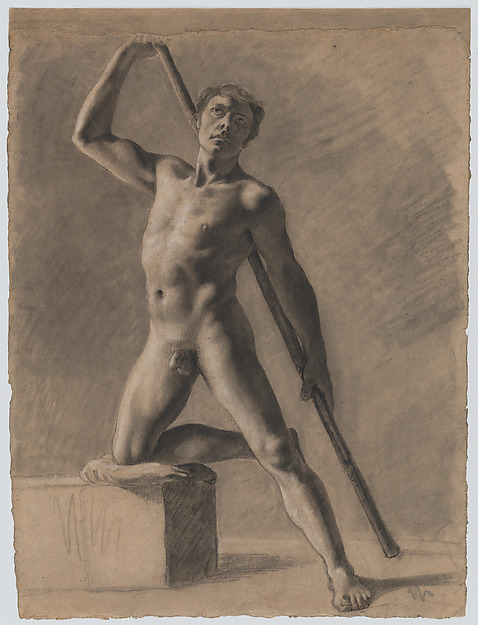

Another drawing that reveals a lot about the artist is ‘Academic Male Nude with a Staff,’ a drawing Delacroix made from a live model. Delacroix was known as a Romantic artist, yet he demonstrates with this drawing that he was more than capable of becoming a neoclassical artist if this had been how he had wished to express himself. The rendering of the forms is magnificent. All of the important broad details are here, beginning with the separation of light and shadow. From this beginning, Delacroix adds the turning edge, the darkest area of the light that melts into the shadow’s edge. There are also the core shadow, reflected light, and the cast shadows.

Delacroix also showed that he was capable of drawing caricatures in his biting sketch of his arch-rival, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. In just a few marvelously expressed calligraphic lines, he portrays Ingres in a manner completely opposed to the graceful, contemplative lines that Ingres would employ. These lines are raw and spontaneous, and Ingres feels exposed.

Immediately to the right of the caricature of Ingres is a line drawing of a lioness. The lioness brings us back to the entrance of the exhibit, where a lone drawing of a crouching tiger is shown. According to the description from the Met: One of Delacroix’s favorite activities was to sketch the lions and tigers in the menagerie at the Jardín des Plantes in Paris.

The crouching tiger is poised for action and is an appropriate representative for the rest of the drawings in this exhibit. The drawings are alive, many of which are poised for action. I highly recommend this wonderful exhibit because these drawings have made me see Delacroix in a deeper way than I had before.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1588396800″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/612B8z2BVpl2BL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”144″]