Summary

- From the 1960s feminists tried to rescue female artists from obscurity. With this goal in mind, Judy Chicago collaborated with other female artists in the creation of The Dinner Party, first exhibited in 1979.

- The installation opens with three banners woven in a Renaissance technique.

- The Dinner Table is set for 39 women from history. It presents women’s contributions and fight for equality, symbolized by the triangular shape of the table.

- Each seat is individualized and carries a distinct look.

- The first wing presents ancient deities, biblical figures, and ancient queens.

- The second wing includes women of the Christian era, saints, scientists, and artists such as Artemisia Gentileschi and Anna van Schurman.

- The third wing presents contemporary explorers, activists, and musicians. The last guest at the table is Georgia O’Keeffe.

- The table is supported by the floor with triangular tiles that have the names of further 999 women written on them.

- As the team research is part of the work, each woman represented on the titles has a short description.

- Over 400 people were involved in the preparation of The Dinner Table which is regarded as one of the most important feminist artworks.

Judy Chicago and the Feminist Art Movement

Judy Chicago was one of the most important figures of the feminist art movement that began in the late 1960s. After centuries of being ignored, a group of female artists began to demand their rightful place in art institutions. When they asked about the lack of representation, the answer was simply that there were no women who deserved it. As a consequence, one of the priorities of these feminists was to rescue the female artists that had remained unknown. They began bringing up all of their colleagues who did not make it into art history books for the sole reason of their gender.

Judy Chicago in front of The Dinner Party, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA, 2018. Photo by Sara Krulwich/The New York Times.

Chicago often collaborated with other female artists. The Dinner Party required the work of hundreds of volunteers and colleagues who specialized in different techniques such as ceramic, china painting, and weaving. It was truly an outstanding effort from every single member of the team. After five years, they finished the installation and it was first shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition opened on March 14, 1979, and drew tens of thousands of people. Although it toured for some time, Chicago always intended to have a permanent home. Today, the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art is its proud host at the Brooklyn Museum since 2002.

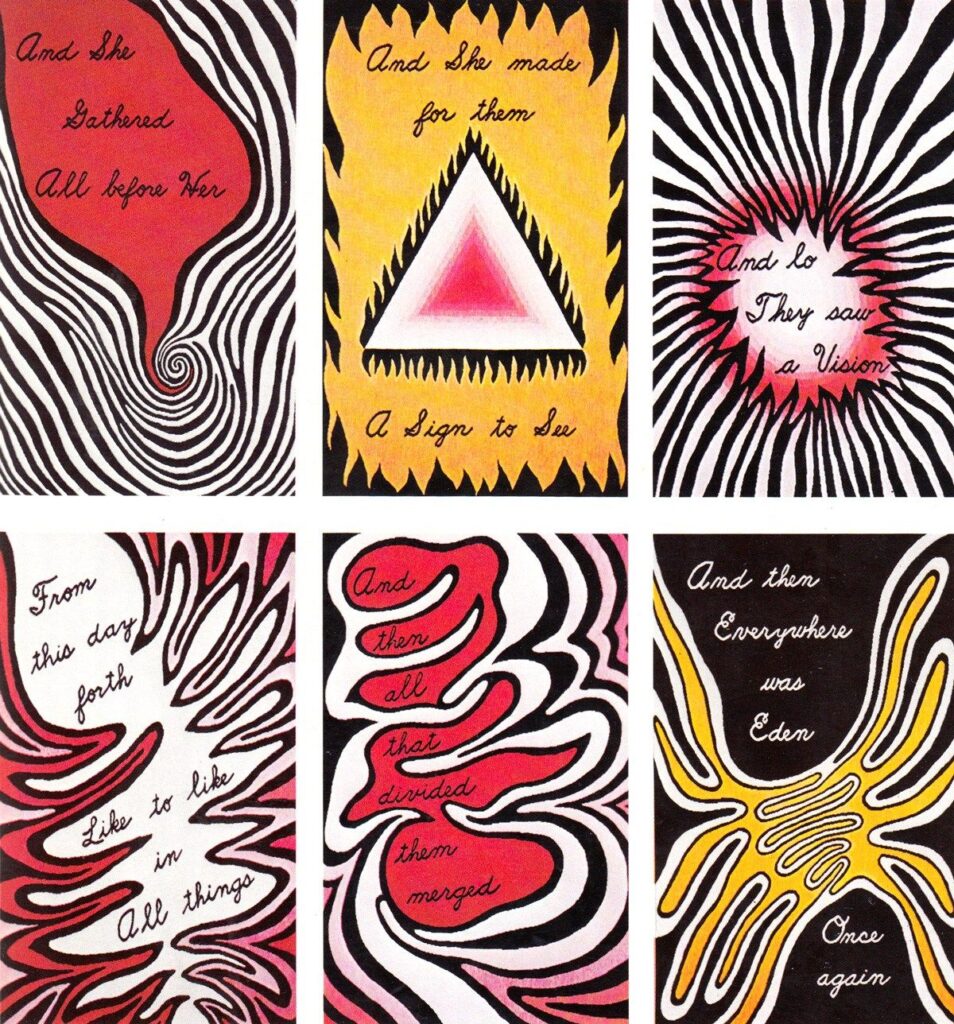

And She Gathered All Before Her

Before we get to the actual Dinner Party, there is a set of six entry banners woven in a Renaissance technique called Aubusson tapestry. For this task, the San Francisco Tapestry Workshop worked with Chicago to train their weavers on the special technique and on the design. Actually, these are the first things that the visitor sees when they enter the exhibition. Furthermore, each one of them has a verse from a text by Chicago that reads:

Judy Chicago, The Entry Banners, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA.

The Dinner Party: Table for 39!

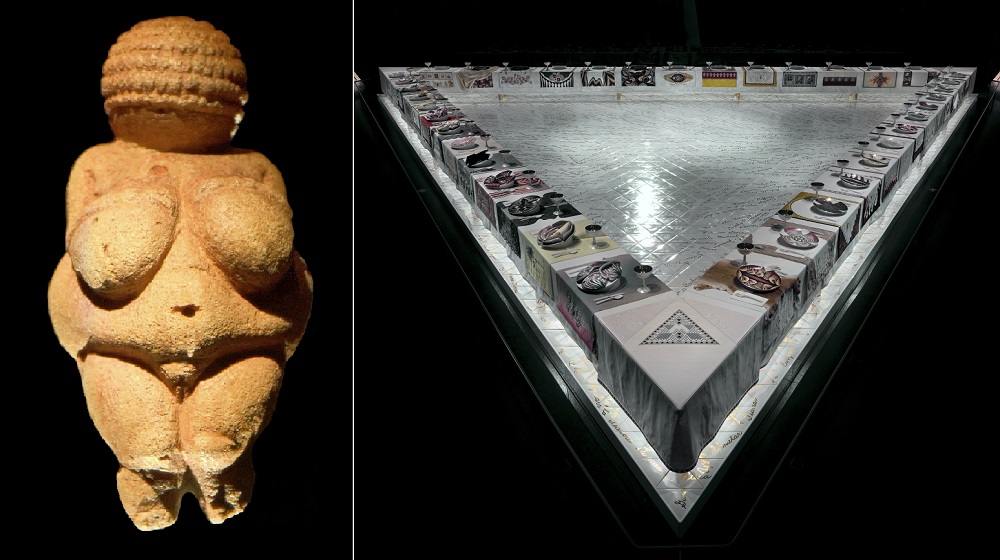

It would take too much time to talk in detail about every single one of these women. Each of them honestly deserves their own article so this is going to be a brief overview. The Dinner Party is set for 39 people. The three sides have seats for 13 of them, divided by historical periods. It offers a chronological review of women’s contributions and their fight for equality. Precisely, the triangular shape of the table represents equality, although an upside-down triangle has been used to represent women since the first civilizations. Moreover, some of the earliest found sculptures depict female figures such as the famous Venus of Willendorf. They often emphasize the pubic triangle, possibly due to the importance of fertility.

Left: Venus of Willerdorf, c. 28,000-25,000 BCE, Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria; Right: Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA.

Personalized Seats

Interestingly, the design of each seat is different. From the plates to the table runner and the calligraphy of their names, Chicago tried to give each one of them a distinct look based on their historical context and their contributions. The initials of their names often are illuminated. Likewise, she used embroidery and needlework from their region and time on each runner. All of the cutlery is the same simple set though. Another thing in common is that all of the plates remind us of female genitalia. As Chicago mentioned in an interview:

It was to make the point that there is nothing that groups these women together who are from all different epochs, eras, countries, races, ethnicities, religions, class, except they had vaginas, which meant we didn’t know who they were!

Nadja Sayej, interview with Judy Chicago: ‘In the 1960s, I was the only visible woman artist’, The Guardian, 2017.

Ancient Badass Women

Goddesses at the Dinner Table

Notably, many seats in this wing are reserved for mythological and biblical figures. The first one is the Primordial Goddess, venerated during prehistoric times. In fact, many early societies, no matter the geographical location, shared the idea of Mother Earth. We can see this belief later in Greek and Roman civilizations and all over the world. Under the plate, the fur symbolizes the clothing of the time and the labor women put into making it.

Judy Chicago, Primordial Goddess at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Biblical Women at the Dinner Table

Judith’s story has appeared for centuries in Western art, but for female artists and feminists in general, her story is even more important. She represents a woman who stepped up and won against an abusive man. Even Artemisia Gentileschi, another guest, depicted her a couple of times and it is known that she used art to cope with her personal history of abuse. That is why Chicago included her at the Dinner Party. See the sword in her name? It is the same one that Artemisia’s name has on her runner.

Left: Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Holofernes, 1611-1612, National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples, Italy; Right: Judy Chicago, Judith at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Queens at the Dinner Table

However, there are historical figures too, such as the female pharaoh Hatshepsut. She reigned over Egypt from 1479 to 1458 BCE, as part of the 18th dynasty. At first, she stepped up as queen regent because the heir to the throne was still a child. Nevertheless, she ruled as any male pharaoh. Interestingly, most of the artworks that represent her depict her as a man with a fake beard and male clothes. However, she used art as a way of legitimizing her rule. Although the next pharaoh tried to minimize her reign, her place in history remained.

Left: Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut, c. 1479–1458 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA; Right: Judy Chicago, Hatshepsut at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Early Christian Badass Women

Saints at the Dinner Table

The second wing is for women who lived during the Christian era up until the Protestant Reformation at the beginning of the 16th century. Here there are no deities, but there are saints. One of them is Marcella, a Roman noblewoman from the 4th century. She had a close intellectual relationship with Saint Jerome and often discussed the Scriptures with him. Similarly, she is commonly represented holding a skull. Eventually, she was canonized and her day is January 31st.

Left: Engraving of Saint Marcella, 1722. Ebay; Right: Judy Chicago, Marcella at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Scientists and Physicians at the Dinner Table

Furthermore, there are women of science such as Trotula of Salerno. In the 11th century, she became the first gynecologist. Incredibly, her work sounds quite modern. She focused on women-oriented medicine, birth complications and even defended the use of opioids during childbirth. She was deeply influential for future generations of physicians attending women. As it happens, it is sometimes debated whether she was a woman or actually a man.

Left: Trotula of Salerno, 14th century, Wellcome Library, London, UK; Right: Judy Chicago, Trotula at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

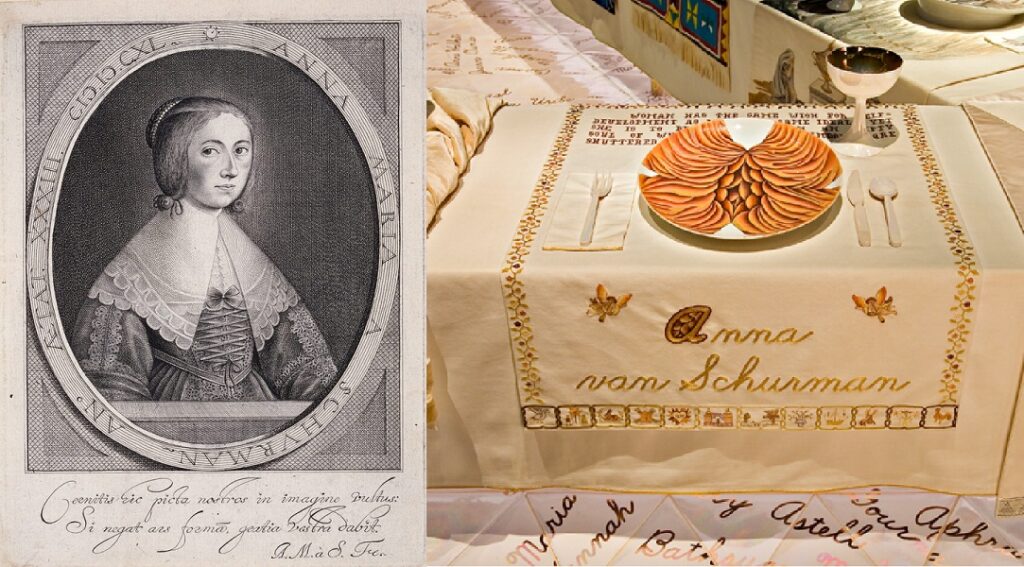

Artists at the Dinner Table

There are a few artists in this wing, one of them is Artemisia Gentileschi who is mentioned before. Arguably, she is the most famous female artist from before the 20th century. Another one was Anna van Schurman, an outstanding woman of the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th century. She received a privileged education and was a polyglot. Moreover, she was an advocate of women’s education and became the first female student and graduate at the University of Utrecht. Added to it, she practiced drawing, painting, and etching.

Left: Anna Maria van Schurman, Self-Portrait, 1640, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, USA; Right: Judy Chicago, Anna van Schurman at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Contemporary Badass Women

Explorers at the Dinner Table

Moving on in history we find the women who lived from the American Revolution up until Chicago’s time. Although most women presented are white, there is some representation of women of color such as Sacajawea. She was a Shoshone woman from today’s Idaho. Unfortunately, she was kidnapped in childhood by a rival tribe and later sold into slavery before being forced to marry a Frenchman. At the beginning of the 19th century, Lewis and Clark recruited her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, for their expedition. However, Sacajawea served as a guide and interpreter as well.

Left: Edgar Samuel Paxson, Lewis & Clark at Three Forks, 1912, House lobby at the Montana State Capitol, Helena, MT, USA. Detail; Right: Judy Chicago, Sacajawea at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Activists at the Dinner Table

Another one is Sojourner Truth, an abolitionist and suffragist from the 19th century. She escaped slavery with her child and won her elder son’s freedom. Even when she didn’t know how to read or write, she published her book Narrative of Sojourner Truth in 1851. She became quite an influential figure in the abolitionist movement, as she was invited to meet President Lincoln. Clearly, her plate reminds the visitor of her African heritage.

Left: Sojourn Truth, 1864, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, USA; Right: Judy Chicago, Sojourner Truth at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Musicians at the Dinner Table

Many of these women wanted to support others in their respective fields. In the case of Ethel Smyth, it was music. In fact, she earned high praise both for her performances and compositions. She combined her passion with her fight for women’s rights and created The March of Women in 1911. This piece became the battle cry of the British Women’s Movement. Her plate represents a pianoforte, probably the only one that does not instantly recall a vulva. Notably, Chicago started to add three-dimensionality to these last plates.

Left: John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Dame Ethel Smyth, 1901, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK; Right: Judy Chicago, Ethel Smyth at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

One More Guest at the Dinner Party

Finally, the last guest at The Dinner Party is a fellow artist, Georgia O’Keeffe. Similar to Chicago, her paintings often featured floral arrangements that resembled vulvas.

Left: Georgia O’Keeffe, Grey Line With Black, Blue And Yellow, 1923, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, USA; Right: Judy Chicago, Georgia O’Keeffe at the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

And Under the Dinner Party

Honestly, 39 women from all of human history seem too few. In reality, each one of them also acted as a representative for the names on the Heritage Floor. As a matter of fact, it can be viewed for its literal function of supporting the table, but also as symbolic support for the women seated at the dinner party. It could be a message about the sorority, as there is no point in having a few women liberated if the rest of them remain oppressed.

Left: The Dinner Party workers painting names on the Heritage Floor Tiles, 1978. Dazledigital; Right: Judy Chicago, The Heritage Floor, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Britannica. Detail.

Furthermore, it is composed of 2,300 hand-cast porcelain tiles in the shape of triangles. In total, there are 999 names that share something with one of the women at the table such as the period, region, or contribution. Diane Gelon and Ann Isolde led the research team to choose all the names and place them. Specifically, they focused on the worth of their contributions to society, and especially to the improvement of women’s lives. The names are written in gold luster. It took them two years working with the China Boutique outside Los Angeles to finish the floor.

For example, the goddesses Coatlicue from Mesoamerica and the Valkeries relate to the Hindu goddess Kali. Meanwhile, Catherine Sforza and Lucrezia Borgia relate to Isabelle d’Este at the table. The famous Madame (Jeanne) Récamier got her name at the Heritage Floor, like many other women who held salons where writers and artists would meet and exchange ideas. At the table, they have Natalie Barney, whose salon hosted the most important artists of the 20th century.

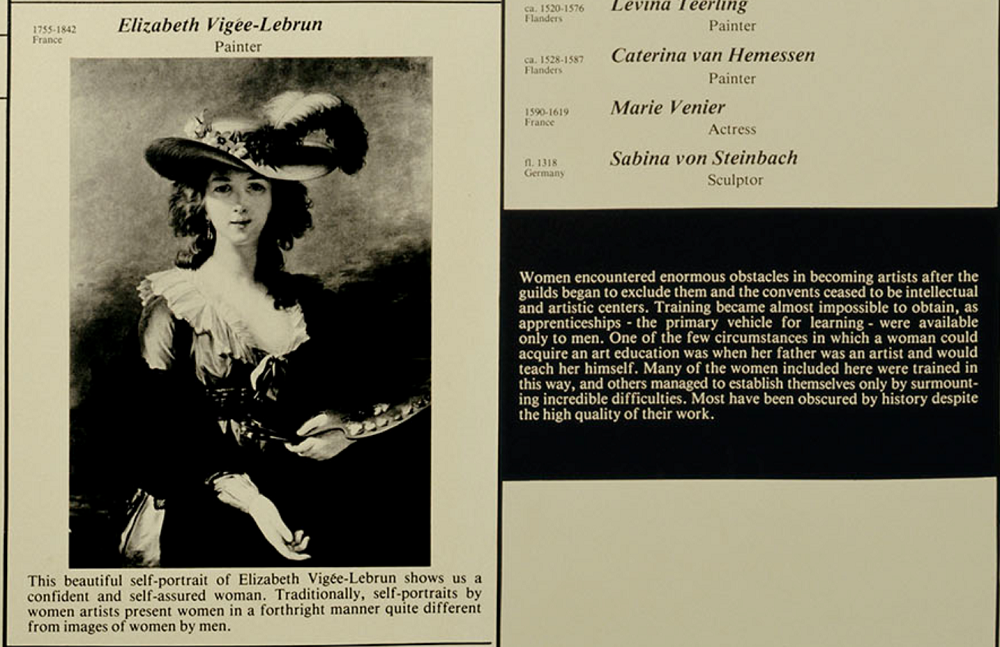

The Heritage Panels

The team research is part of the work in the Heritage Panels. There is a brief mention of each of the names on the Heritage Floor, their lifetime, and their contributions. Additionally, there are photos and examples of their art or other works, depending on their field of expertise. Some of them have a longer explanation.

Judy Chicago, Elizabeth Vigeé Le Brun at The Heritage Panels, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

It Took a Village

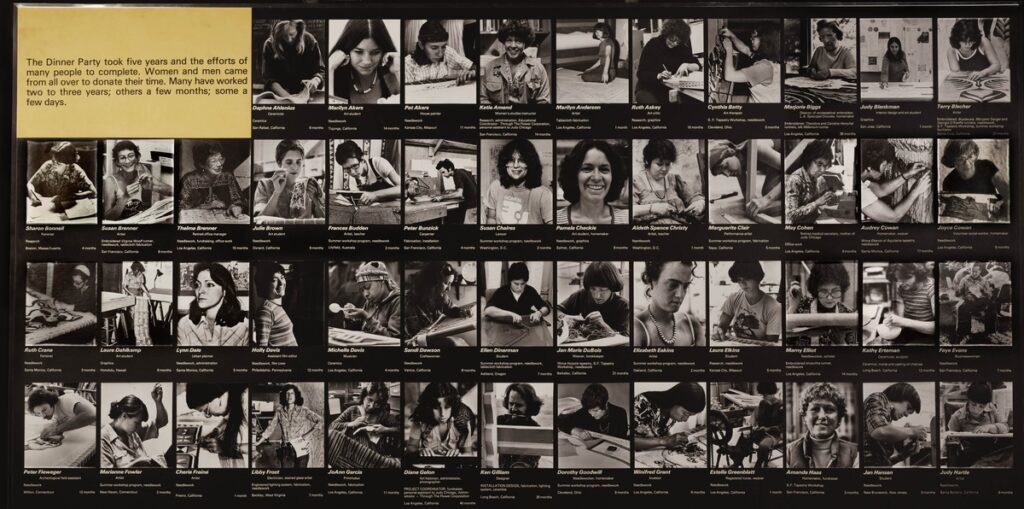

Though Chicago was the mastermind behind The Dinner Party, she relied on an excellent team to complete her vision. There was a core team of 20 or 25 people, some of whom actually received a salary. Moreover, the Acknowledgment Panels include black-and-white photos of 129 members of the administrative and creative team. Furthermore, there are 295 names written by other collaborators.

Judy Chicago, The Acknowledgement Panels, 1974-1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA.

Legacy of the Dinner Party

Since the first time it was displayed to the public there were women contacting Chicago. They wanted to thank her for her work and to tell her how inspiring it was. However, the critics were not so pleased. Many did not consider it a true artwork and others were particularly offended by the designs of the plates. Regardless, today the Dinner Party is one of the most important feminist artworks in Western Art.