It’s a small and relatively unknown museum but it offers a great collection of modern and contemporary South American and international art. And just as interestingly, it has a fascinating history! It was founded for the benefit of the people of Chile by president Salvador Allende – only two years before he was murdered in a coup d’etat in 1973.

We don’t often hear about the history or the behind-the-scenes of museums, do we? In the Allende museum this was the part I found the most captivating, besides learning more about South American art.

Solidarity Museum: 1971-1973

The museum was founded in 1971 in the Chilean capital, Santiago, under the government of the leftist president Salvador Allende. The idea was to create a museum for the people of Chile, which would be composed of works donated by Latin American and international artists who agreed with the ideology of the museum (and therefore of the government). Its mission was therefore to reach and educate the wider population who would otherwise not have access to such fine art. Many internationally known artists – such as Joaquin Torres Garcia or Pablo Picasso – responded to the call of solidarity and shipped their donation as a support to the Allende government.

Years in Resistance: 1975-1990

The museum however, despite quickly growing an important collection, struggled to become officially registered, and this became its fate. After the 1973’s military coup d’etat, when the infamous dictator Augusto Pinochet grabbed the power, the museum had to dissolve its collection. They transferred to a temporary location the works that they physically had in collection, and diverted those that were currently under shipment. Part of the works was parked in the Chilean National Fine Arts Museum (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes), others found a temporary home in other institutes. Between 1975 and 1990 the museum functioned in exile as an institution of the Resistance, with works of foreign artists and exiled Chileans.

Museo Salvador Allende: 1991-Nowadays

Since 1991, the museum is back in Santiago, operating under the name of Museum of Solidarity “Salvador Allende”, in honor of the restored democracy and the memory of its socialist patron, Salvador Allende.

But the story of the museum doesn’t end here! At that point the museum started to get its collection back, but the process wasn’t easy. In some cases it’s been incredibly difficult to retrieve the artworks from their temporary custody, since the museum was not legalized back then. The temporary placement of some artworks wasn’t documented properly, others got lost during shipment. On some occasions, the Salvador Allende Museum fought hard over the possession of important paintings with the other institutions providing the “temporary” home. They had to involve the testimony of artists if they were alive. Although the process is not finished to this day, the majority of artworks found their way back and are on display in the beautiful colonial mansion in the Republic District. Today the museum houses more than 2700 works from 1300 national and international artists.

The Museum Building

An interesting fact: during the military dictatorship the building was used as the headquarters for the National Intelligence, the institution of state repression, persecution, assassination and abduction of politicians from the opposition. In the rooms where the paintings are shown at present, the National Intelligence had installed a phone surveillance system.

Fancy visiting Chile’s capital? Read about what to see in Santiago and practical tips.

Discover the South American Art Collection of the Salvador Allende Museum

With such a history, many artworks’ accompanying texts not only describe the usual facts about the artist or the piece, but also detail their trajectory, from acquisition up to their current place on the wall. I found very interesting that every work had a story behind it. Although the museum collects internationally, in the following I’m going to introduce my favorite pieces from South American artists.

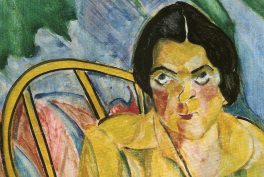

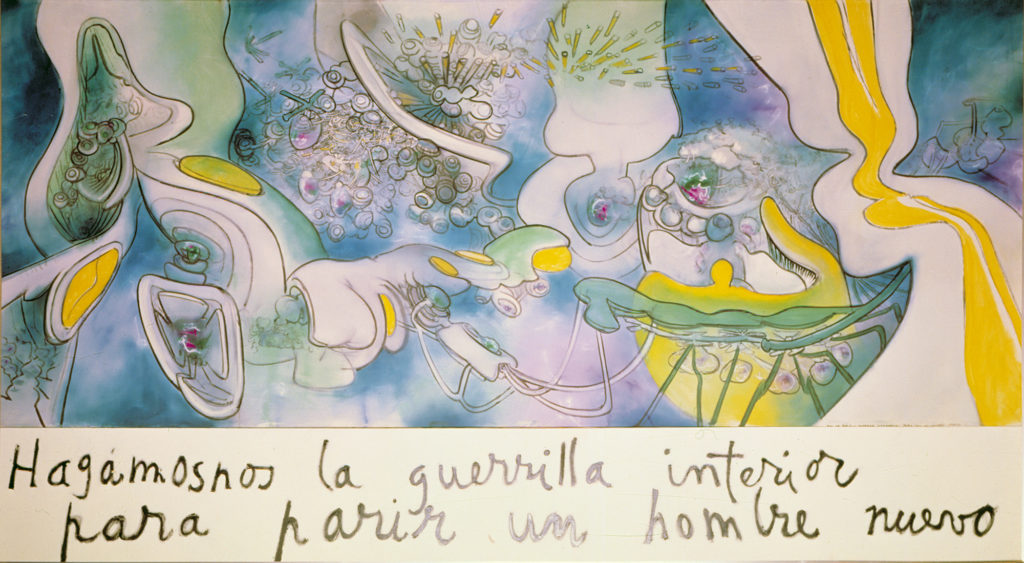

Roberto Matta: Let’s Fight Ourselves from Within to Give Birth to a New Man

Let’s begin with the most prominent painting in the museum, made by one of the most (if not THE most) famous painters of Chile. We’ve seen his works in many other South American museums, like in MALBA or – surprisingly – in the Botero Museum in Bogotá, Colombia. So I’m happy to present him from the collection of a Chilean museum.

The Story of Two Paintings

Roberto Matta was an active supporter of Salvador Allende and the progressive liberation movement. He sent two large format paintings to the museum in 1970 and they were displayed next to each other in the initial home of the – then-called – Solidarity Museum. In 1974, after the coup, both of these paintings were placed to the Chilean National Fine Arts Museum on the request of its director.

Once there, the paintings were added to their inventory and displayed, but without any reference to their original collection. In the case of Let’s Fight Ourselves from Within..., it was displayed without the lower part with the title. In 1991 Roberto Matta sent a certificate testifying that the paintings were donations to the Solidarity Museum. He decided that Let’s Fight Ourselves from Within… should be reinstalled in the Salvador Allende Museum with the text at the bottom, and the other painting should remain in the Chilean National Fine Arts Museum.

Matta’s Political Paintings

Matta is regarded as an important figure of South American surrealism, despite being political in his works (most surrealists look introspectively and are not political). His style is recognizable by the imaginary sci-fi landscapes. Some critics call these paintings “inside landscapes”: faded blue-green-yellow colours in pencil-like technique and large-scale format characterize them. He admittedly created these pieces based on “hallucinations” that he had after the first brushstrokes. From the 1960s on, Matta’s works revolved around Latin American history, when different countries faced dictatorship.

Let’s Fight Ourselves from Within… depicts an abstract place that could be a laboratory. The only objects that I can clearly see are the bullets and remote controls connected to structures, perhaps to a destroying machine. In the original Spanish title (Hagámosnos la guerrilla interior para parir un hombre nuevo) the “guerilla” word is present. Guerillas are an important part in South American history: a group of clandestine people who fought for a political ideology different from the one in power. Perhaps this painting is Matta’s shout to destroy the perpetuated order and give space to a new order that is embodied in socialism.

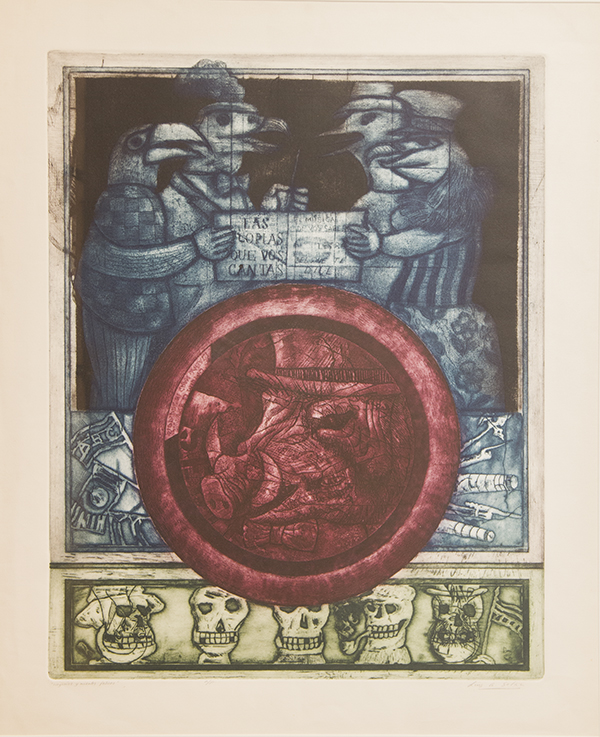

Luis Alberto Solar: Allegories and Happy Deaths

Carnival is one of the most celebrated events in South America. Unfortunately I didn’t get to see it during my trip there but have seen a few exhibitions in museums and heard about it from locals. I would love to experience it next time I come to South America! When you think of carnival, don’t only think of Rio de Janeiro with its samba and the shiny bikini girls but of a more traditional type of carnival (as is still practised by many indigenous communities). In these carnivals, people wear face masks of typical characters, such as the Devil, the Queen, the African, etc. who have their own personality and represent an archetype. So that’s why the carnival-themed work of Solari raised my attention in the Salvador Allende Museum.

Solari’s South American World of Carnival

Solari’s world is a magical one, based on his childhood carnival experience from his hometown, Fray Bentos, in Uruguay. In his works he brings in elements of the Uruguayan folklore and traditions. On his most famous pictures, he depicts carnival characters in animal masks, who are always the most striking figures of the image. But the painting goes beyond the reference to carnivals: this sort of duplicity of personalities represent human vices and social issues like greed, anger, hypocrisy, sabotage while death is also present as the inevitable end.

Under the Magnifying Glass: The Allegory and Happy Death

The Allegory and Happy Death is a piece parted in colours: blue, red and green. On the upper part, there are human figures masked as birds, wearing hats and suits, holding a document – like a pact they signed – that says: “the verses you sing” in Spanish. Solari often used proverbs, verses or popular sayings as a folkloric element in his paintings. The red part in the middle looks like a seal and depicts a wild boar in a top hat and tie. Next to it in blue, there are flags and weapons. Finally, at the bottom, we see skulls. The whole composition reminds me of Orwell’s book The Animal Farm, where the group of animals symbolize society. In my opinion, on Solari’s picture the bird-masked figures represent war mongering – the moment when people in high position agree on an act that will influence many lives, but they are actually puppets of something bigger, death.

Etching Technique

Solari made the picture with the etching technique: a printmaking method involving the use of acid to carve on metal. He learnt etching in Paris where he studied 3 months in a workshop. He kept working with this technique throughout his career, creating some of his most famous artworks.

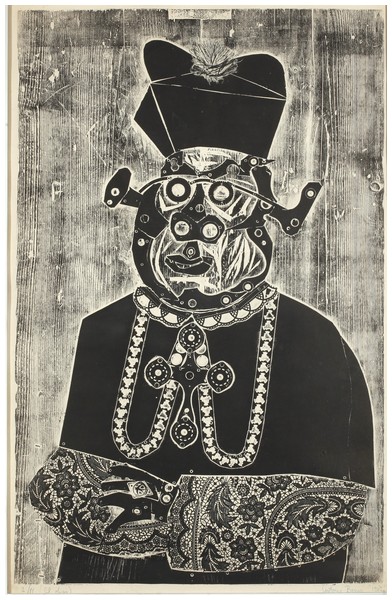

Antonio Berni: The Bishop

An alien with funny tube ears trying to dress up as a human? Quite right. Monstrous-looking characters are typical of Antonio Berni, who is one of the most famous painters throughout Latin America. His works are exhibited in many prestigious museums on the continent and our series showcasing South American art cannot pass by without featuring him.

Topics and Characters from Argentina

The Argentine Berni became well-known for his new-realistic paintings revolving around the social issues of 1930s Argentina: unemployment, poverty and the effects of industrialisation. Later, he painted a series of works featuring his fictional characters. They are Juanito Laguna (representing the typical person from the slums in opposition to the wealthy aristocracy) and Ramona Montiel (a humble young girl who tries to take regular jobs but after all finds herself stuck in prostitution and consumerism).

Berni’s Political Paintings

Berni’s work is overtly political: “In my case, I admit it, I think that the political reading of my work is fundamental, that it can not be left aside, and if it is left, it cannot be fully understood. What’s more, I think that a mere aesthetic reading of my work would be a betrayal.” No wonder then, that he donated a painting to the Solidarity Museum in its first years. The Bishop is a character from the Ramona Montiel series, the social archetype of hypocrisy. Its alien face is in contrast with the typical position of leaders on portraits and religious clothes. I understand this as a clear statement about the outrageous reality of the church, and the image it is still trying to maintain. Alongside the bishop, Berni depicted other social characters such as the pope, the confessor, the criminal, the colonel.

Engraving Technique

The artist used the engraving technique for many of his works, like in the case of The Bishop. I find the black and white picture quite contrasting with his other works, which are very colourful – however figures represented as sort of monsters often appear on other paintings too. He created many works with a similar technique, which he discovered himself and called xylocollage. This method also produces black and white images, so those works can be linked to The Bishop and the Ramona series.

Laura Márquez: Composition

During our visits to South American art museums we’ve hardly seen any work by Paraguayan painters. Some critics say that the world is so occupied with understanding the underdevelopment and isolation of that country, that the art scene is not regarded at all. Other critics state that art in Paraguay hasn’t found its own voice yet. Anyhow, considering Composition by Laura Márquez as an example, it’s a loss that (even the South American) public doesn’t get to know these works. I was positively surprised to find this piece from a Paraguayan female artist in the Salvador Allende Museum.

The Avant-garde Painter

Laura Márquez is an avant-garde painter, who labels herself as South American artist. She is considered a pioneer of modern Paraguayan art. According to her own memories about the time she lived in Paraguay, she was eager to keep inventing and exploring anything she could about painting: forms, concepts, methods of creation. As a result, if we take a look at her oeuvre, we notice that her works are made in various styles (such as abstract, cubism) and are reminiscent of international artists or trends.

Buenos Aires, the Hub of South American Art

She studied in Buenos Aires; an important hub in the South American art world at that time. There, regional artists could learn about foreign tendencies (from Europe and the USA). By the 1960s many South American artists could produce works completely fitting to North American concepts of technological advancement and modernism. On the other hand, this type of modernism and technology was not the reality in the Southern part of the continent. Thus the question arose among the art scene: whether to follow the “universal” line or produce a regional reality.

Read about Djanira da Motta e Silva and Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, two Brazilian artists who chose their regional reality above the universal line.

A Paraguayan Painting

Laura Márquez successfully transmitted these global trends and styles to Paraguay and complemented them with local traditions to create a unique world. Composition is a great example of this: on the pop-art-style, multicoloured circle – which is clearly influenced by the trend of that time – she pinned a ñandutí, a typical lace made in Paraguay. The painter regarded ñandutí as local pop art-like form. The whole painting looks like a beautiful kaleidoscopic image with bright, vibrant colours. Márquez often used geometric forms in her paintings, especially circles, which is understood in local traditions as the symbol of the sun.

In 1970, Laura Márquez moved to New York City, the cosmopolitan city of art, where she still lives today.

Address: Av. República 475, Santiago, Chile

Entry: 1000 CPL, free on Sundays