The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre is a force to be reckoned with. Writer, director, and social commentator, he has recently written a book titled The Displaced, set in his native city of Los Angeles. The novel was published by Arte Publico Press on 30th June 2022.

D’Ebre has a passion for exploring urban politics and understanding the culture of street gangs. This Mexican-American writer grew up in Los Angeles in the 1980s and 1990s. He knows the culture of punk, rap, skateboarding, and graffiti, and it shows. He brings the neighborhoods of his teens vividly to life before our eyes.

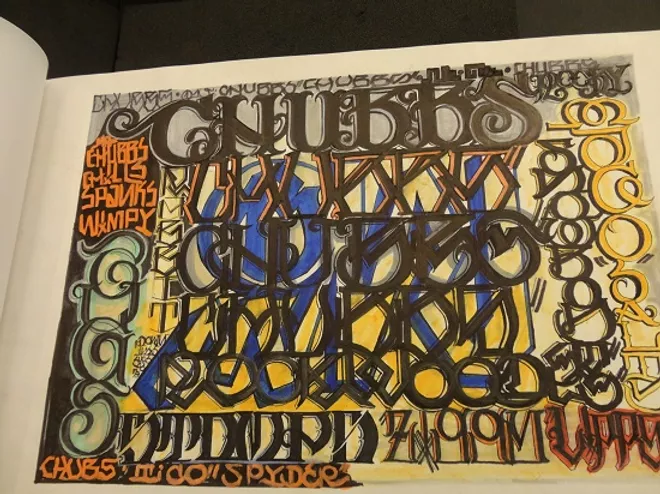

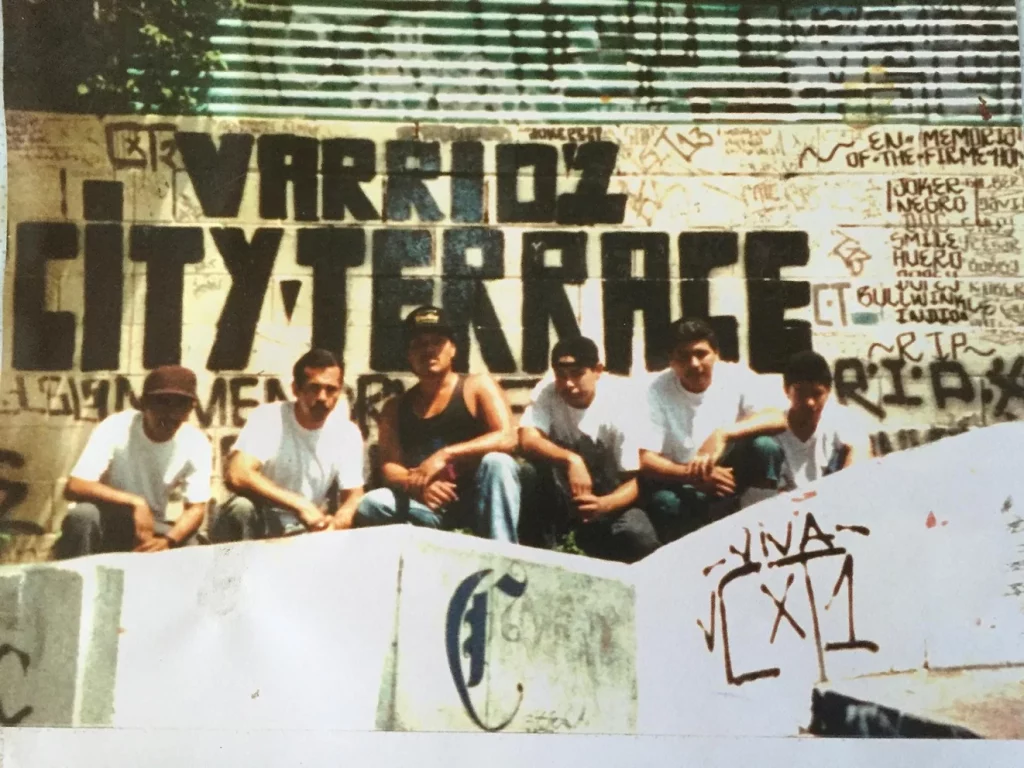

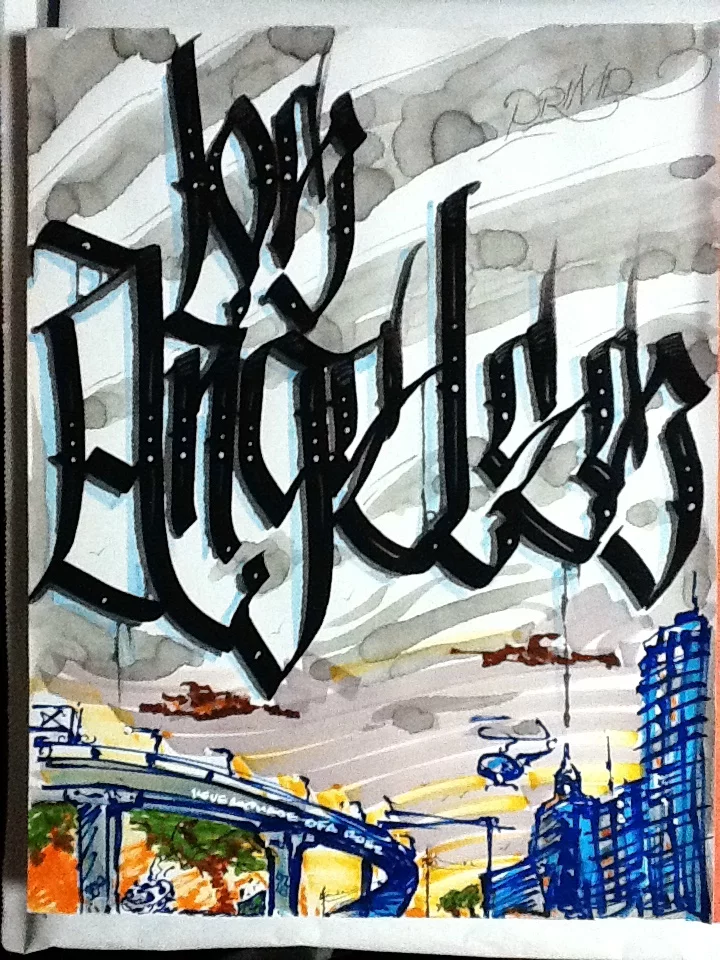

Still from the film Dark Progressivism, written and directed by Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre, 2015.

D’Ebre wrote and directed the documentary Dark Progressivism, which is a deep dive into Los Angeles gang graffiti, murals, and tattoo art, and the impact of street art and underground art on contemporary art and culture. This is well worth a look.

In Ribera d’Ebre’s The Displaced, the residents of a Mexican-American / Hispanic neighborhood respond to gentrification with extreme violence. Gentrification is the process where the character of a poor area (usually urban) is changed rapidly by an influx of wealthier people. The original residents are usually displaced by rising land and property prices and communities are broken up.

Still from the film Dark Progressivism, written and directed by Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre, 2015.

The action takes place as the year 2000 approaches, and Y2K conspiracy theories create a political hot-house atmosphere. An influx of hipsters to Culver City in West Los Angeles, a poor neighborhood of Mexican-Americans, sets off a chain of events that end in a bloody battle. Developers and land agents rename the area as Silicon Beach. They aggressively buy up and re-sell shops and houses, which pushes already desperate people into violent reactions. The incomers are representatives of the white, middle-class, young population, looking for a cool lifestyle change. If white skin is a kind of armor in the world, the characters in this book believe that weapons of destruction are the answer.

The story centers around three characters – Mikey, Lurch, and The Doctor. Mikey is a clever working-class kid, desperate to leave his run-down neighborhood, but also lacking the confidence to walk away from the only world he knows. Lurch is a gangster who lives for the power of his role within the community. While he believes he wants to protect the neighborhood, he seems to offer it very little except for violence, oppression, drugs, and guns. The Doctor paid his way through medical school selling drugs, and he has returned to “give back” to the community. But he seems confused about where he fits in. A plan to violently expel the incomers turns into a bloody war scene with armed police, hostages, and gun battles.

Still from the film Dark Progressivism, written and directed by Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre, 2015.

This is, of course, a parable, a fantasy. Like all speculative fiction, this is not a manifesto for action. Back in 1729 political satirist, Jonathan Swift suggested in A Modest Proposal that the poor people in Ireland should sell their children as food for the rich. The Displaced novel feels very much in that vein. This is an anarchic push-back against white gentrification. Let’s remember that the decades of actual history and fictional novels most definitely encouraged young white men to use violence to take what they wanted. Colonialism is a tragic tale of white supremacy and genocide. The fact that this is a story of people of color taking back control will stir up some very uncomfortable feelings for people on all sides of the political spectrum. And rightly so, D’Ebre is clearly asking some difficult questions.

This is a very US novel. Urban planning, policing and gang culture are not quite the same in the UK and mainland Europe. But gentrification of various kinds is happening all over the globe. In the UK inner city, housing estates get bought up and redeveloped, and the people who have made it into a community get priced out and moved on. However, I have seen first-hand how progressive social housing and community-led regeneration schemes help mitigate this, laying down rules to protect communities, and ensure that very real long-term advantages are enjoyed by the original inhabitants. D’Ebre in The Displaced seems to say that this is not the case in the USA.

Still from the film Dark Progressivism, written and directed by Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre, 2015.

There are two problems everyone in this novel labor under – rampant capitalism and toxic masculinity. The few women in the book are stereotypical – the hard-working, beaten-by-the-system Mom, and the unavailable sexy girlfriend, who is lusted over by everyone, but who is promiscuous and shallow. But later, in a necessary plot twist, this giggling “airhead” is revealed to be a successful and high-profile union organizer. The white migrant women are two-dimensional victims of vicious misogyny.

Each chapter is narrated by one of the three characters, and the switches between them add skillful pace and drama. This is a fast, fascinating read. The nods to D’Ebre’s heroes are a little clunky. He is very open about his writing inspirations, but at times it feels more like a young writer’s recipe book than a fully independent work. A large glug of Albert Camus, a pinch of Joseph Conrad, season with Ralph Ellison, simmer, then turn the heat up to the max.

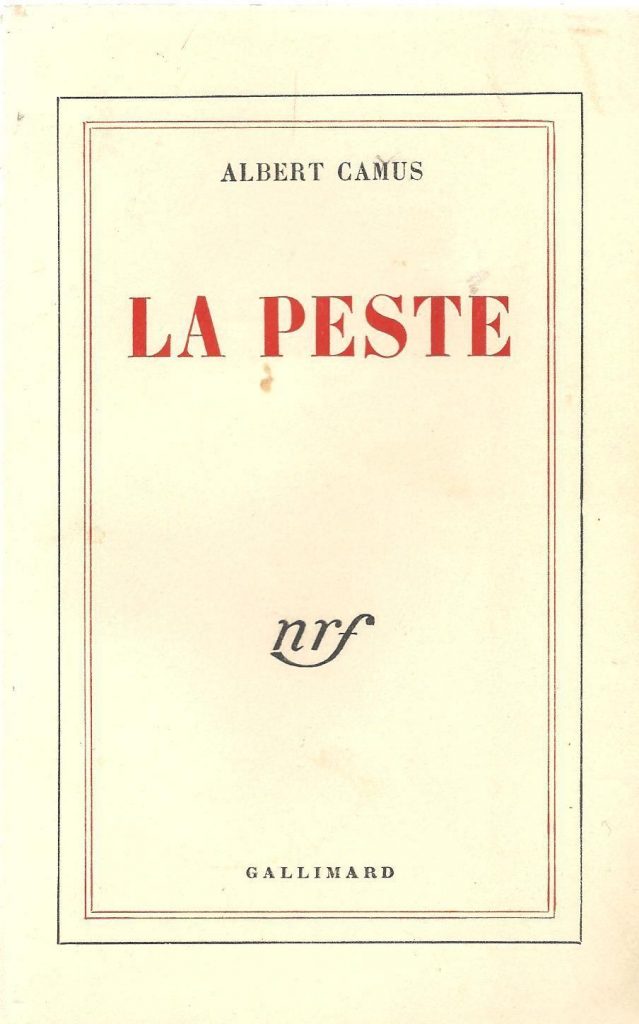

Albert Camus, La Peste, first edition book cover, Gallimard Press, 1947.

The author openly references his homage to Albert Camus’ existential novel The Plague, which is a 1947 novel about a town in the grip of a deadly plague, considered by some to be an allegory of the French resistance to Nazi occupation. However, comparisons to the Third Reich and the Jewish Holocaust do not do Ribera D’Ebre’s The Displaced any favors.

I find the parallels between the Nazi occupation of Paris and the gentrification of Los Angeles too much of a stretch, even in satire. People unfairly ejected from the neighborhoods they have built and loved is a story that stands alone on its own merit. Aligning brutal genocide with city gentrification is unnecessary. The residents of The Displaced were unfairly bribed with cash and holidays, not a one-way ticket to the gas chamber.

The question that D’Ebre digs deep into is – how do we find our place, without disenfranchising others? D’Ebre himself sought education and moved to a richer, more fashionable area. For the population there, he is the incomer, the cool young interloper. Communities in transition are a fact of humanity. Migration is literally embedded in our ancestral DNA. Cities came into being as humans crossed continents in the mass migrations of industrialization. All cities are an organic, shifting mass. But as D’Ebre reminds us, it is always the poorest who lose out. In a broken system, the city will never adequately shelter those who need it most.

In the history of Los Angeles, the Indigenous people were practically wiped out by Christian-Spanish explorers and missionaries. Spanish, Mexican, then white Anglo-American rule was devastating to the Native American population of Chumash and Tongva / Gabrieleño peoples. Imported by the early settlers, racism, slavery, and land grabs were much in evidence during the genocidal eradication of Native American populations across America. The protagonists of The Displaced don’t reach this far back in their history.

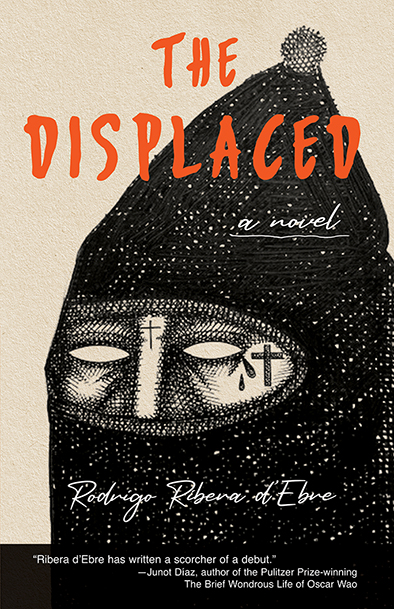

Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre, The Displaced, book cover, Arte Publico Press, 2022.

The dialogues between the characters feel real: we hear insecure men who feel that deep, honest communication makes them vulnerable. Some dialogues feel less authentic – the three main characters repeatedly spout black adaptations of the white supremacy theme of “if they don’t look like us, they don’t belong here” and the white characters speak like racist automatons.

The tragedy of white racists attacking people of color has been highlighted by the Black Lives Matter movement. In Ribera d’Ebre’s The Displaced, the horror and absurdity of racial origin and skin color defining your place in society is turned on its head. Mexican Americans brutally murder any white citizen, whatever their background, politics, or reason for being there. In one episode, a young man with learning disabilities is slaughtered, along with his young female carer, by a gang of young people, simply for being on the wrong street. Of course, this is what is happening to young black men every day across America. And this novel wants to remind us of that with grim, stomach-churning satire.

Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre. crimereads.com.

A narrative that relishes a hyper-masculine warrior/gang culture is going to feel uncomfortable and take occasional missteps. But D’Ebre wants us to think about why we manage cities (and people) the way that we do, and how we could handle it with compassion and humanity. This novel feels like part one of a narrative journey, and D’Ebre certainly has intelligence, humor, and insight. This novel is not for the faint-hearted, but we definitely want to see more of this writer.

The Displaced by Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre was published by Arte Publico Press on 30th June 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!