The Schloss Collection: A Story of War, Looting, and Restitution

Among the many artistic depredations that devastated France under Nazi rule, the looting of the Schloss collection came to be seen as a defining...

Javier Abel Miguel 1 September 2025

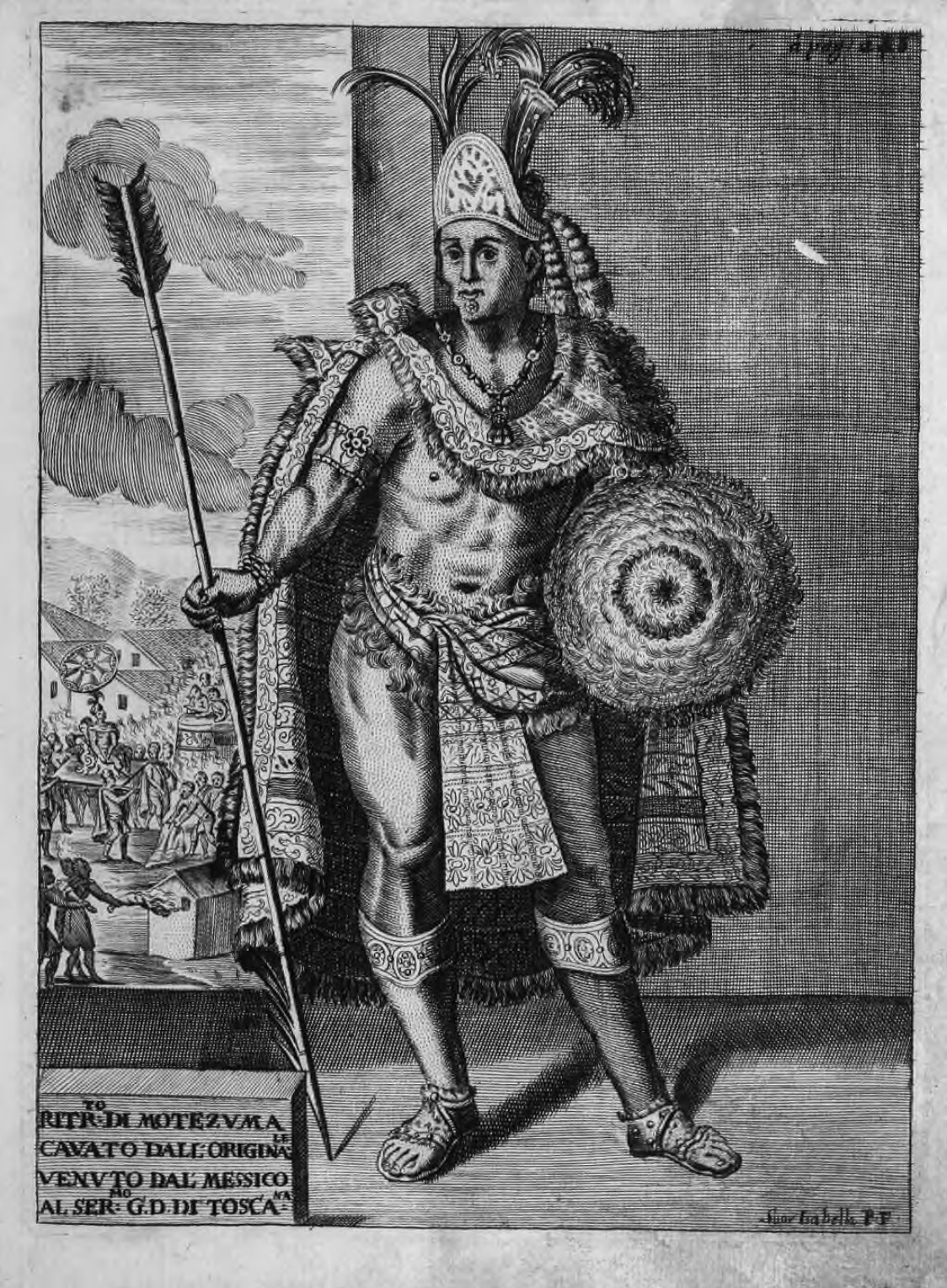

Throughout Mexico’s rich history, two significant milestones have shaped its identity: the fall of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec city that laid the foundation for modern Mexico City, and the liberation from Spanish dominion. These pivotal events hold great importance and continue to influence the country’s cultural heritage. A focal point of national pride is the legendary headdress believed to have once belonged to the renowned Aztec emperor – Moctezuma. However, the journey to reclaim this symbol of Mexico’s past has encountered unexpected challenges, as the current custodians show reluctance to part with it.

In October 2020, writer Beatriz Gutiérrez Müller was sent by her husband Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the president of Mexico, to several European countries which currently host some of the most precious pre-Columbian pieces of art and historic documents (according to Miguel Gleason, the director of the Mexican Culture Institute in New York, there are over 9,000 Mexican objects dispersed across Europe and the States). Her task was to convince the owners to send the pieces to Mexico for a national exhibition marking the anniversaries. Yet the mission turned out to be mission impossible, especially regarding the expected highlight of the show, Moctezuma’s headdress.

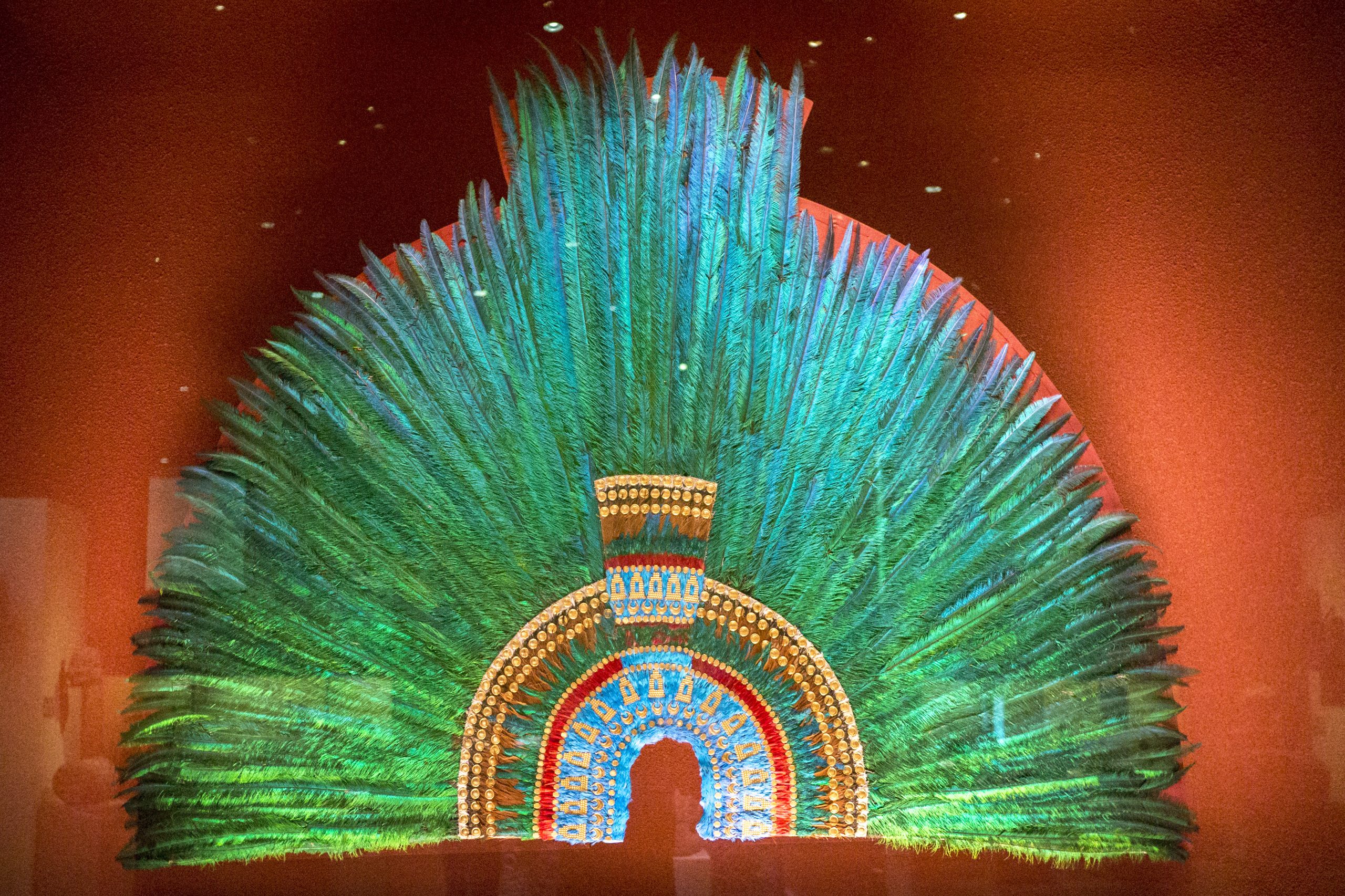

What is the object in question? It’s the only pre-Columbian headdress that has survived until today. It’s widely believed to be a panache, some argue that what is known as “Penacho de Moctezuma” is in fact a cape traditionally worn by priests. The cape argument is supported by the large size of the object, 1.3m in height and 1.78m in length, but it weighs only a kilogram, which makes it easily wearable as a headdress.

Semi-circular, it’s made of over a thousand feathers of various colorful bird species, one of them being quetzal, characterized by the beautiful scintillating green plumage. Just imagine the scale of the enterprise, and the value of the headdress, as each quetzal bird carries just from 2 to 3 such feathers in their tail. Then, there are brown feathers of the squirrel cuckoo, pink ones from the roseate spoonbill, and blue ones from the cotinga. If you add 1544 metal elements, 85% of which are gold and 10% silver, you get a bomb of beauty and value.

Feather-working was one of the most prestigious arts in this region of pre-Columbian America. Consequently, amantecas – feather artisans – had an elevated status within Aztec society. They produced fans, headdresses, capes, and shields for the nobility, priesthood, and knights, and especially for the Eagle warriors, a special military class. To make a feathery object, first; they made a paper template of agave or tree bark on which they drew a desirable form. Then, with natural adhesives, they attached the feathers to the template, starting from the exterior; working toward the interior of the object. The decorations in the center of the piece would be added last. To achieve the polychromatic effect, the feathers of various, often rare, birds were used.

The first European document mentioning the headdress was an inventory of the nephew of the Spanish King Charles V, Austrian Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol who acquired it in 1596. But it is unknown how the headpiece entered the European market. Some say that Hernan Cortés stole it from Moctezuma II, others say that the Emperor offered it to Cortés as a welcoming gift in Tenochtitlan in 1519. In any case, in a letter to Charles V, Cortés mentioned a “feather headdress” as one of the 160 Mexican gifts for the king. Nevertheless, since 1596 the headdress has remained in Austria and in 1878, the director of the Weltmuseum in Vienna, Ferdinand von Hochstetter, led the process of its deep conservation.

Although the attribution of the headdress to Moctezuma II is not confirmed, the dispute over its rightful location has been on fire for 40 years. Mexico offered various deals, but Austrians don’t even want to lend the tiara for any period of time, arguing that the object’s condition is too poor to survive even light movement. Mexican scholars agree with Austrians, as exemplified by Prof. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, an archeologist and historian, who said that the headdress would need a large container that would mitigate any sort of vibrations during transportation. As no such container has been constructed, there is no way to move Moctezuma’s headdress even by a millimeter.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!