Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

While we are all familiar with celebrity culture and can recognize all of the Kardashians by their silhouettes, the idea of ‘celebrity’ is not a new one. In the 19th century, a notorious French actress, who became known as ‘The Divine Sarah,’ could arguably be called the first celebrity. But, was Sarah Bernhardt just a ‘superstar,’ or was there more to this incredible woman than her fame?

Sarah Bernhardt was born in France in 1844, the illegitimate daughter of a Parisian courtesan. Henriette-Rosine Bernard, as she was baptized, was destined to lead an unusual life.

Her original plan to be a nun was not the path that her mother saw for her, and it was with the backing of her mother’s patrons that Henriette was placed in an audition for the Paris Conservatory. Although not the most talented actress, her enthusiasm was enough for the committee to invite her to become a student.

Her early performances with the Comédie-Française were not successful, and it was not long before she left the company, following a violent argument with one of the leading ladies, Madame Nathalie.

From this point onward, Sarah Bernhardt veered between fame and infamy. She moved to another theater company, The Gymnase, but following another scandal, she decided that it was time to travel. With letters of introduction, Bernhardt found herself associating with the higher echelons of society. An affair with a young Belgian aristocrat, Prince de Ligne, resulted in the birth of Sarah’s only child, Maurice.

To support her young child, Bernhardt returned to the stage. As her roles began to increase, her fame grew, spreading across Europe and America. With her level of fame, it was inevitable that she would be immortalized in art.

With the term ‘actress’ often seen as a synonym for a prostitute, the fact that Bernhardt sat for respected artists gave her acting career legitimacy that we now take for granted. Here, French artist Gustave Doré produces the first portrait of Sarah Bernhardt. She looks distinguished, wearing a beautiful high-necked dress coat, with her hair piled high under the feathered hat. The side view adds to this respectful aspect, as most portraits of the well-to-do would be positioned this way.

By 1870, Bernhardt was wealthy enough to provide support during the Franco-Prussian War and she organized a refuge for injured soldiers returning from the front. It seems suitable that Dore should represent Bernhardt in this way.

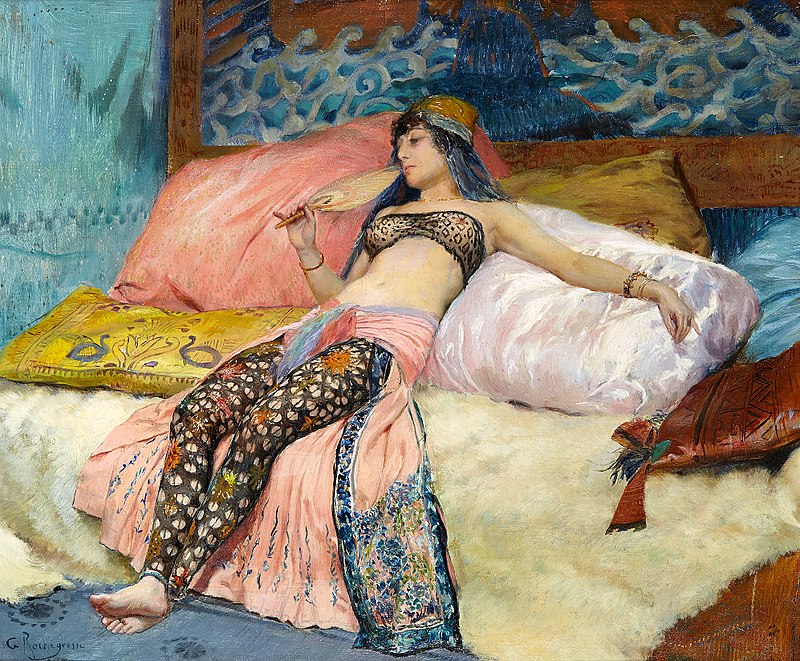

This undated painting by George Rochegrosse shows Bernhardt in the role of an odalisque. The sumptuous fabrics and furnishings are enticing, and her languid pose invites us into this boudoir of delights. The Divine Sarah was known for her numerous, well-connected lovers, who included Bertie, Prince of Wales, and novelist Victor Hugo.

A change of image occurs in this 1889 portrait, with its ‘saintly’ qualities; the gold leaf background was reminiscent of icons. Her head, gently leaning to the right, looks out at the viewer with such a small smile. Everything about this portrait demonstrates her versatile acting ability.

Large numbers of portraits were done of her various roles, and here she plays Lady Macbeth as an exotic femme fatale, gazing up towards those spirits that she calls upon to ‘unsex me here.’

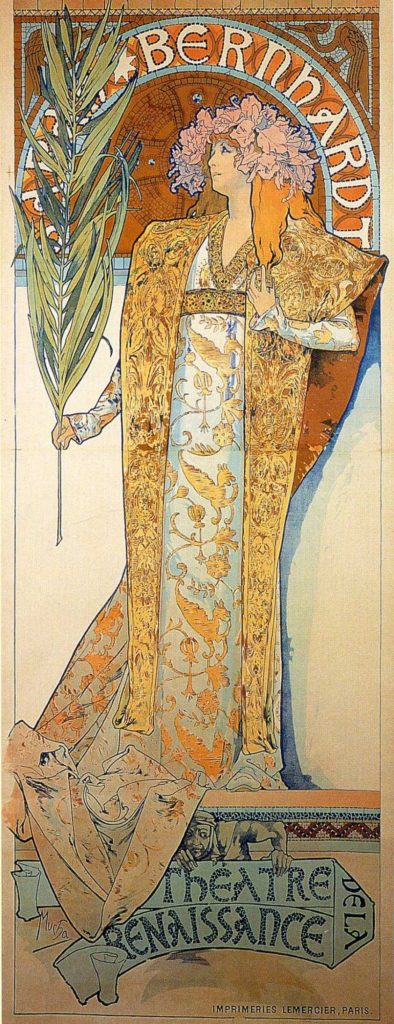

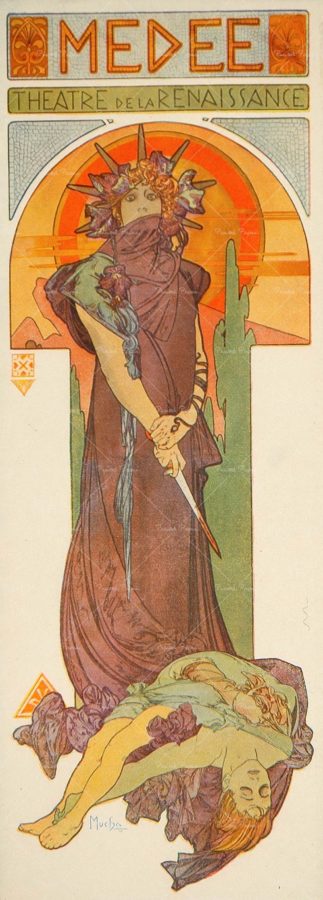

However, where Bernhardt’s skill in representation truly came about was with her collaboration with a young man, Czech-born artist Alphonse Mucha, and a new art form. In contrast to the prudery and hypocrisy of the Victorians towards the female form, Art Nouveau celebrated the body in its use of curvilinear forms, loose flowing hair, and diaphanous clothing. Little wonder it was looked upon as shocking and decadent.

Leading poster artist, Alphonse Mucha, utilized this newfound freedom. He believed that through the creation of beautiful works of art, life could also be transformed. This may seem idealistic until we see its use in the more practical posters.

The example here, Gismonda, advertised an 1894 play starring and directed by Sarah Bernhardt. Her Byzantine costume is perfect for this: exotic, vibrant, and colorful. The figure is placed on a stage and the elongated body, draped in this magnificent costume, reveals her beauty and the nobility of her character. The lettering, too, is elongated and curvaceous, with each letter holding its own space. The color palette reflects the opulence of the Byzantine era; golds and blues dominate. Bernhardt holds a palm leaf in her hand, symbolizing victory and the bearing of the character reflects that strength.

Poster after poster was produced in the next decade. Mucha had discovered a winning formula, and Sarah was all for supporting the young artist who, in turn, immortalized her into a superstar status:

Not only would Sarah be immortalized on canvas but in sculpture as well. This piece by Jean-Léon Gérôme is a stained marble bust, typical of Gérôme. He depicts Sarah as if she is on stage, costumed in male attire. The symbolic features around the bust add a heightened sense of the drama—a trait that never left her.

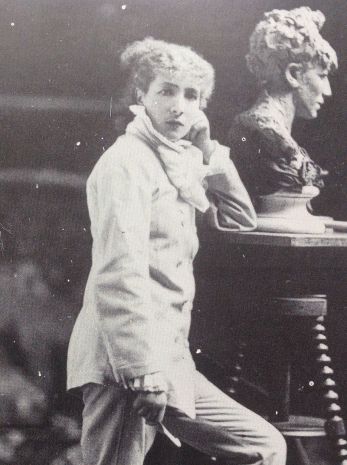

However, Sarah was not only keen on sharing her art through acting; she was also tempted into sculpture herself.

In the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC, there is this large marble sculpture by Sarah Bernhardt. A keen painter, Sarah had also taken an interest in sculpting, and, alongside her acting career, she took lessons with Mathieu Meusnier and Emilio Franchesci.

Après la tempête (After the Storm) depicts a Breton peasant woman cradling the body of her grandson who had been caught in a fisherman’s nets. Sarah Bernhardt had seen this woman on the seashore and was moved by her story, which ended tragically with the death of the child. But in Bernhardt’s sculpture the child’s right hand grips the woman’s garment, perhaps suggesting the possibility of a more hopeful ending.

Après la tempête catalogue entry, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, USA.

When exhibited in the Salon of that year, it won the Silver Medal, which is not surprising as the rendering of the figures is so lifelike and full of pathos. The fact that there may be a happy ending demonstrates the positive attitude that Sarah had toward life.

However, it is this gorgeous bas-relief marble, recently sold at Sotheby’s in London for £308,750, that is truly stunning. It details the moment in Hamlet where Ophelia’s death is described:

Her clothes spread wide;

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up:

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes;

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element: but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.William Shakespeare, Hamlet, act IV, scene VII, 1609.

The innocence of Ophelia is played down here, and Bernhardt creates a sensuous image of the young girl as if in the throes of ecstasy, rather than the moment of her death.

Bernhardt also sculpted portraits of people around her. This bust features a fellow artist Louise Abbema, who was only 23 when Bernhardt created this piece and, it was rumored, was Sarah’s lover. Bernhardt presented it at the Paris Salon in 1879.

At the turn of the century, Sarah Bernhardt turned her attention to film. Yet another example of the superstar embracing all forms of her art, the first film adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet starred Sarah, not as her famous stage role of Ophelia but as the eponymous hero himself:

This new art form was perfect for someone who knew how to emote on stage. Sarah was not afraid of embracing a new medium and threw herself into many film productions. This still from one of her films reveals how this new art form could bring her emotion to the masses.

One of her most famous roles was as the tragic courtesan in Camille and here we see her portraying her at the age of age of 65!

Despite being in her 60s, Sarah was still touring, making films, and appearing all over the world. Sadly, Bernhardt’s accident in 1906 resulted in gangrene and her leg was removed. But did this put a stop to the indefatigable siren? Carried on a white palanquin, Sarah traveled France, entertaining the troops and becoming the army’s sweetheart!

Sarah continued acting right up until her death in 1923. Of all the actresses from the period, no one epitomized the idea of a superstar more than she did, and no one appears as artistically versatile as ‘The Divine Sarah.‘

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!