Summary

- A 2021 audit revealed a prevalence of the statues of white men and animals in London’s public space over women.

- The number of statues is even lower when it comes to women of color.

- Statues of women are dominated by the members of the Royal family and anonymous, allegorical figures.

- Noor Inayat Khan was a Muslim Indian princess, British spy, and radio operator during World War II.

- Mary Seacole was a nurse who fought racism and nursed British soldiers in the Crimean War.

- Violette Szabo’s sculpture commemorates British secret agents during World War II.

- Millicent Fawcett was a union leader who campaigned for women’s right to vote.

- Edith Cavell, a Red Cross nurse, treated soldiers of both sides of World War I in Belgium.

- Catherine Booth, a Christian feminist, fought for a right to women’s voice at public meetings.

- Sarah Siddons was an 18th-century actress who dominated the London theater scene.

- Joan Littlewood was a popular theater director.

- Mary Wollstonecraft was an 18th-century author and radical who promoted women’s rights.

- Virginia Woolf was an author and icon of feminism.

- The Untold Stories program is one of the ways London tries to increase the visibility of women and minorities.

- 2020 was a turning point when some now controversial statues of men have been removed from public space.

What does London mean to you?

London is considered to be the most popular capital city in the world. Impressive huh? What do you think of when someone says London? Tourists flocking to the palaces? A cultural melting pot of languages, nightlife, shopping, and food? Astonishing museums and art galleries? Yes, without a doubt. So far, so fantastic. But London is also known for some less savory characteristics. Try these on for size: money laundering capital of the world? Highest rates of child poverty in the UK? 1 in every 52 people homeless while multi-millionaires hoard empty properties as “investments”? And old Londinium doesn’t really fare any better, as it was the historical center of the global slave trade.

Patriarchs celebrating patriarchs

London belongs to rich white men, so when a 2021 audit by ArtUK and Pack and Send revealed that almost all of the public statues in the city are of rich white men, it didn’t come as a huge surprise. Women and people from minority ethnic backgrounds don’t really get a chance to take part. In fact, there are more statues of animals in London than there are of named women. They do love their animals, those patriarchs. Although I do have a soft spot for Elisabeth Frink’s Paternoster of a shepherd with his sheep (shown above), and at least it is by a woman!

Elisabeth Frink, Paternoster, 1975, London, UK. Photo by Tony Hisgett via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

Women are seriously under-represented

If you’re interested in the statistics, London has almost 1,500 statues, more than a fifth of which are dedicated to named men. Just 4% are dedicated to named women and the numbers keep dropping, only 0.2% are of women of color.

As The New York Times dryly commented: If humankind vanished tomorrow and aliens arrived from another galaxy, they wouldn’t be faulted for believing that the whole of human history was composed of men on horseback.

Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey, Statue of George IV, 1843, Trafalgar Square, London, UK. Photo by Aaron Bradley via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Royal Women

If we dig further into the numbers, it just gets worse. The majority of female monuments are dedicated to women from the Royal family: Queen Victoria comes off especially well, with nine (yes, nine) statues. This to honor the woman who oversaw a devastating famine in Ireland and the spread of racist British colonial rule across much of the globe.

Sir Thomas Brock, Queen Victoria statue, 1924, Buckingham Palace, London, UK. Royal Parks.

Headless, Faceless Women

Unless they have royal blood, Londoners seem to prefer their female statues to be nice, anonymous girls, devoid of personhood. Think allegorical figures celebrating abstract ideas or fictional characters. With titles like Headless Woman (Nymph) you get the picture.

Headless Woman (Nymph), Crystal Palace, London, UK. Invisible Palace.

But let’s take a look at some of the (very) few statues dedicated to real women in London and celebrate the fact that they are out there. Let us walk past the hundreds of grey old men on horses, and head for the parks and palaces where great women await us.

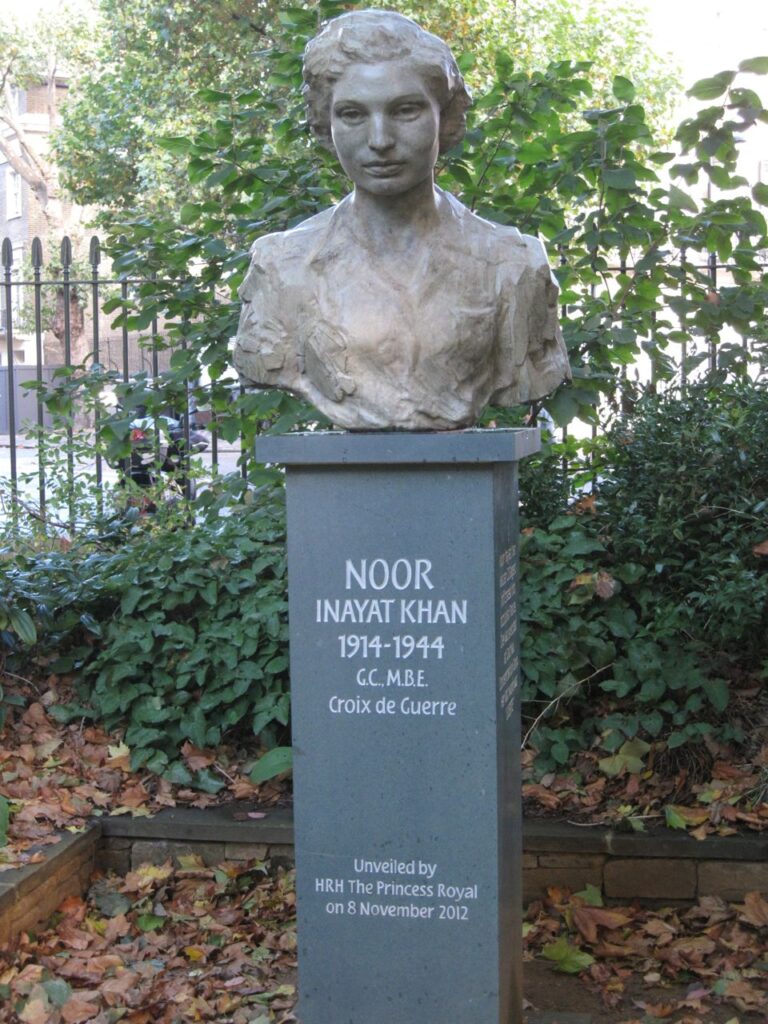

1. Noor Inayat Khan

The bust of Noor Inayat Khan, by sculptor Karen Newman, was erected in 2012, in Camden. This Muslim Indian princess was a spy for British military intelligence during World War II and was the first woman radio operator to be sent to occupied Paris. She was born in Moscow, studied at the Sorbonne, and although a pacifist, decided that she had to help crush the Nazi threat. Tragically, she was betrayed by a double-agent and was executed at Dachau concentration camp in 1944.

Karen Newman, Noor Inayat Khan, 2012, London, UK. Photo by Henk van der Wal via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

2. Mary Seacole

It took 12 years of campaigning to get a statue of the Jamaican-born nurse Mary Seacole approved. It stands on the the grounds of St Thomas’ Hospital. Seacole nursed British soldiers in the Crimean War. She is also known for combatting racism throughout her life. The sculpture is by Martin Jennings and stands in front of a 4.5 meter-high disc, cast from shell-blasted Crimean rock. On the subject of Crimean nursing, Florence Nightingale is also commemorated with a statue in Waterloo Place.

Martin Jennings, Mary Seacole, 2016, London, UK. Mary Seacole Trust.

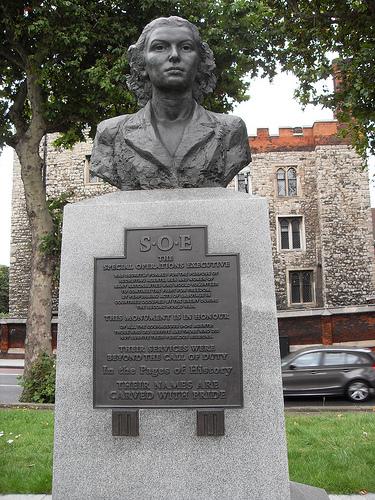

3. Violette Szabo

The bust of Violette Szabo on Albery Embankment was created by Karen Newman to commemorate the heroism of those who served as secret agents and risked their lives during World War II. London-born Violette Szabo was known as a crack-shot and was fluent in both French and English. She was captured by the German army, interrogated, tortured and deported to Ravensbruck, a German concentration camp, where she was executed aged just 23.

Karen Newman, Violette Szabo, 2009, London, UK. Artist’s website.

4. Millicent Fawcett

This suffragette was the first woman to be added to Parliament Square. Fawcett was a pioneering feminist, intellectual and union leader who campaigned for women’s right to vote. The statue was designed by Turner Prize-winning artist Gillian Wearing and portrays Fawcett at the age of 50, when she became president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. The names and images of 55 women and 4 men who actively supported women’s suffrage also appear on the statue’s plinth.

On the subject of Suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst also has a memorial near the Palace of Westminster. It was originally installed in 1930, two years after Pankhurst’s death, after concerted campaigning and fundraising by her fellow suffragettes. Conservative MP Sir Neil Thorne wanted the statue moved to Regents Park, which he felt was a more prominent location. But women were in an uproar, stating that the original position was chosen by the Suffragettes. Thus the statue remains, as a warning to the dangers of ignoring women, to this day.

Gillian Wearing, Millicent Fawcett, 2018, London, UK. Photo by Garry Knight via Wikimedia Commons (CC0).

5. Edith Cavell

Edith Cavell was a British nurse who worked with the Red Cross in occupied Belgium during World War I. She treated both armies and helped hundreds of Allied soldiers escape to the Netherlands. She was arrested in 1915 on the charge of harboring prisoners of war and was executed by a German firing squad. The 3 meter high sculpture was designed in 1920 by architect Sir George Frampton who was criticized at the time for his modern, symbolist style. Cavell’s words “Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone,” were later added to the plinth at the request of the National Council of Women.

Sir George Frampton, Edith Cavell, 1920, London, UK. Photo by Robert Cutts via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

6. Catherine Booth

This statue of the Salvation Army Mother, Catherine Booth, was unveiled in 1929. Booth was an early Christian feminist and became a powerful speaker in her own right, breaking the convention that women were not allowed to speak at public meetings. It was made by British sculptor George Edward Wade who was a largely self-taught artist.

George Edward Wade, Catherine Booth, 2015, London, UK. Photo by GrindtXX via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

7. Sarah Siddons

Sarah Siddons was a Welsh-born actress who left 18th century audiences swooning with her charisma and talent. She dominated the London theater scene for many years. Her statue, by French sculptor Léon-Joseph Chavalliaud, was unveiled in 1897 on Paddington Green and is based on a portrait The Tragic Muse by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Leon Joseph Chavalliaud, Sarah Siddons, 2014, London, UK. WikiData.

8. Joan Littlewood

Another theatrical statue, this bronze called The Mother of Modern Theatre can be found outside the Theatre Royal. Joan Littlewood was an English theater director, who forever broke the barriers between “popular” theater and “arts” theater. The work was created by Scottish sculptor Philip Jackson, noted for his modern style and emphasis on form.

Philip Jackson, Joan Littlewood, 2015, London, UK. Theatre Royal Stratford East Twitter.

9. Mary Wollstonecraft

One you will no doubt have seen debated is the recent Maggi Hambling sculpture of Mary Wollstonecraft. This 2020 statue of the Mother of Feminism has been loved and hated in equal measure. Born in London in 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft was an 18th-century author and radical who promoted the rights of women. Her daughter was the writer Mary Shelley.

Maggi Hambling, Mary Wollstonecraft, 2020, London, UK. ArtReview.

10. Virginia Woolf

Let’s end on an absolute corker. Virginia Woolf was an English writer and considered one of the most important modernist 20th century authors. A bronze bust by Stephen Tomlin was erected in 2004 in Tavistock Square, a copy of an original likeness from 1931 which is held by the National Portrait Gallery. Woolf’s works have inspired women for years and she is an icon of feminism. Aurora Metro Arts and Media, a London-based charity, campaigned for five years to get a life-size statue of Virginia Woolf sited in Richmond-on-Thames, where she lived. It was eventually unveiled in 2022.

Stephen Tomlin, Virginia Woolf, 2004, London, UK. Art Site.

Laury Dizengremel, Virginia Woolf bench, 2022, Richmond-on-Thames. Photograph by Miranda France via X, 2023.

Representation Matters

Portrait sculpture has undoubtedly had its heyday. In the 18th and 19th centuries, you were tripping over royalty, prime ministers, military figures, and captains of industry set in stone and bronze. Our heroes are, quite rightly, changing. Furthermore women’s role (and voice) in society has changed too.

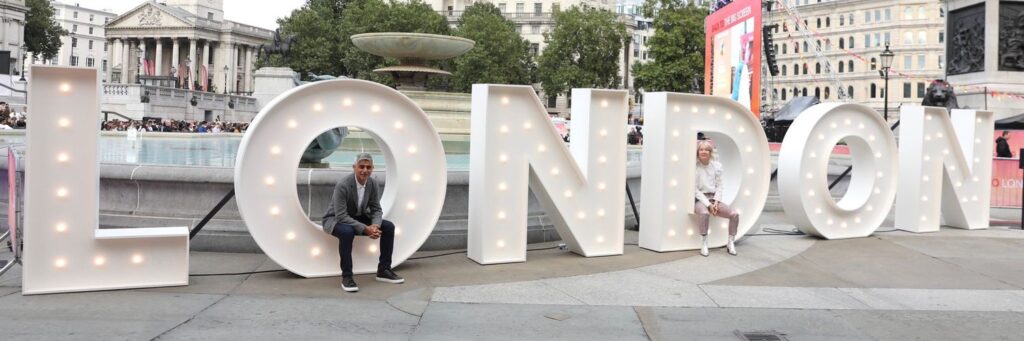

Untold Stories

In 2021 the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has announced a £1m fund to champion diversity in London statues and public spaces to make sure they better reflect the city as a whole. The Untold Stories program sees grants of up to £25,000 available for projects to refresh public spaces. The money can be used for murals, street art, street names, and other projects.

Khan has said that London’s diversity is its greatest strength and he is right. However if its statues, buildings, and street names honor only a minority of the population then that gives locals and visitors alike a badly distorted view. It is time to rethink our public spaces and who we honor within them.

Launch of the Untold Stories campaign by Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London, 2021.

Statue Toppling Protests

Protests focusing on symbols of oppression have made front page news across the world recently. A turning point occurred in June 2020 when a statue of Edward Colston was removed from its plinth in Bristol (a large slaving port) and thrown into the harbor. Colston was deputy governor of the Royal African Company who held the English monopoly on slave trading. Colston was temporarily replaced by Marc Quinn’s statue of the Black Lives Matter protester Jen Reid, her fist raised triumphantly in the air. The conversation has started.

Edward Colston statue toppled by protestors in Bristol harbour, 2020. BBC.

Where Next?

But where next? Identifying problematic statues is a start. Next discussions must take place about removing some statues, or relocating them to museums or gallery spaces where they can be set in context. Is it even possible to re-think and re-make some sculptural works? Then the exciting job of coming up with ideas for new works arises. A reckoning is coming, whether we like it or not, and that is surely something many Londoners (and the rest of us) can celebrate.

Who would you suggest for a monument in London? Share your thoughts with us!

Marc Quinn, A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) statue, Bristol, UK. 2020. Photo by Alex Richards via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).