The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

9 September 2024 min Read

The Golden Age of the Dutch Republic was a flourishing period for culture and economy, yet it wasn’t characterized by peace. The Dutch Republic engaged in the Eighty Years’ War from 1568 to 1648 against the Spanish Empire for independence. Throughout this period, artists actively sought to instill a Dutch national consciousness within the populace. In this article, we’ll explore six propaganda prints to understand the process through which the Dutch became Dutch.

Willem Pieterszoon Buytewech, Allegory on the Deceitfulness of Spain and the Liberty and Prosperity of the Dutch Republic, 1615, etching, engraving, and drypoint, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, MA, USA.

An enclosed garden, a group of people, and two dangerous animals; what do these things have in common with the Dutch Republic and their national identity? This is the most known allegory of the Golden Age of Holland. The source of this representation is the medieval story of the Virgin Mary, who appears in a closed garden, a symbol of her purity. Likewise, we can see the Maid of Holland sitting in the flourishing and rich garden, a symbol of this glorious era. Furthermore, the association between country and woman is important in the construction of the Dutch national identity. In premodern mentality, women were considered beautiful but also fragile and vulnerable. Consequently, women must be protected, the same way a country needs protection. This print was produced during the Twelve Years Truce (a ceasefire during the Eighty Years’ War), and we can see the imminent attack of Spain, which is personified as a woman waiting outside the garden.

Frans Hogenberg, Spanish Fury, 1576-1578, etching, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Keep your friends close and your enemies even closer. In this print you can see how the Dutch used a pejorative image of the Spanish to construct their own contrasting identity. Hogenberg represents a scene from the Eighty Years’ War, when the Spanish army attacked a city in the Dutch Republic. Interestingly, in this print the Dutch appear as civil, surprised by the spontaneous attack of the Spanish. As a result, this image highlights their religious identity: while the catholic Spanish are depicted as brutal murderers, the Dutch seem to be innocent protestants wanting to practice their religion in peace.

Adriaen Collaert, February, 1578 – 1582, etching, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

This print can be succinctly described as embodying the essence of winter and the joy of life, both intimately tied to the national identity of the Dutch people. Firstly, the winter landscape holds immense popularity in the Dutch Republic, given its geographical context. Paintings depicting winter scenes, reminiscent of works by Jan Brueghel the Elder, have become iconic representations. Winter serves as a powerful symbol of the Dutch national identity, in stark contrast to the warm and summery landscapes prevalent in the art of the Spanish Empire. Secondly, the depiction of joyous individuals in this print signifies a sense of carefree contentment. Even amid wartime, the evident happiness suggests a deep trust in their leaders, reflecting the prevailing sentiments of the time.

Claes Jansz Visscher, Windmill Near the River, 1613, etching, The British Museum, London, UK.

The windmill has a large symbolic presence in Dutch print representation. It can be seen as an innovation of engineering, but also it is connected to the Dutch national identity. Windmills are necessary for harnessing the power of the wind, and their invention is associated with the power of the Dutch over nature. In this print, we can see a man who carries a sack of grain. Moreover, it suggests that agriculture prospered despite the unfavorable climate.

On the other hand, some poems and prints associate the windmill with the Orange Dynasty (the current reigning house of the Netherlands), because:

And Prince who serves his office well, shows all diligence and humility that his subjects and the burghers prosper and have good relation […] indeed the Windmill suffers the blow of all winds, in order to throw out the water…

Sinnepoppen, 1614. Rijksmuseum.

Anonymous, Dutch Camp in Mauritius, 1619, etching, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

The expansive colonial empire of the Dutch Republic played a pivotal role in shaping their national identity. In this print, an anonymous artist vividly portrays a colonial territory, emphasizing its Dutch ownership by natural law. The scene feels oddly familiar, depicting Dutch individuals engaged in various activities at their homes, such as fishing, barrel construction, and boat building. Simultaneously, the exotic nature of the territory is evident through its distinct flora and fauna. This deliberate blend of familiarity and exoticism serves to attract the Dutch bourgeoisie to invest in the colonial territory, presenting it as a secure and prosperous place.

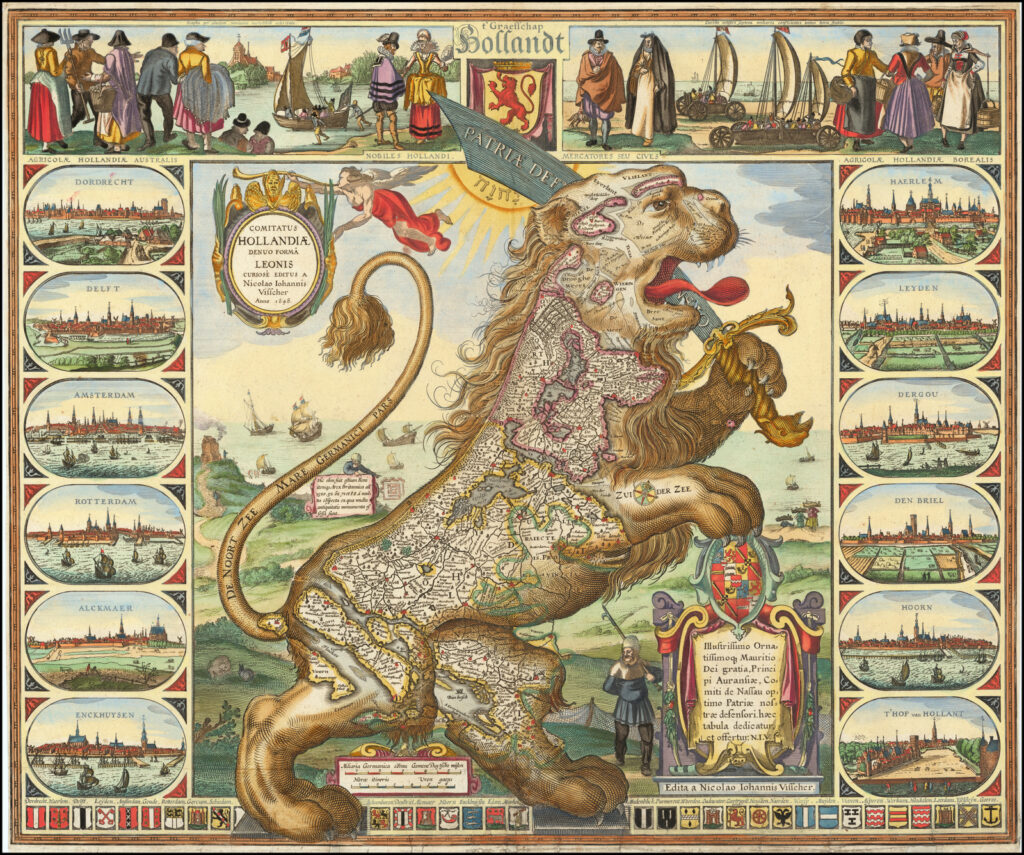

Claes Janszoon Visscher, Leo Hollandicus, 1648, engraving, Atlas van Stolk Museum, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

In 1648, the Dutch Republic won its independence at the end of the Eighty Years’ War. This map by Visscher represents a consolidation of the country. Similarly, this suggests the consolidation of the national identity of the Dutch people. We can see Leo Belgicus, a leitmotif of the period, in an offensive position, ready to fight against any enemy. Furthermore, in this print Leo is in its complete form, Leo Hollandicus. Moreover, it symbolizes the people of the Dutch Republic, who will ever defend their country. The artist also added some vignettes with the most important cities to represent the economic power of the Dutch Republic. We can see the diversity of people which made the country famous for their tolerance in the upper side of the print as well.

Alexis Metzger: Enjoying the ice. Dutch Winter landscapes, weather and climate in the Golden Age, 17th

century, in Climate of the Past, 2020, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-81, (accessed 11.11.2023).

Amanda Pipkin: Rape in the Republic, 1609-1725. Formulating Dutch Identity, Brill, Boston, 2013.

Amanda Pipkin: “They were not humans, but devils in human bodies”: Depictions of Sexual

Violence and Spanish Tyranny as a Means of Fostering Identity in the Dutch Republic in

Journal of Early Modern History, No. 13, 2009, pp. 229-264.

Alison McNeil Kettering: Landscape with Sails: The Windmill in Netherlandish Prints in Simiolus:

Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, No. 1/2, Vol. 33, 2007/2008, pp. 67-80.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!