The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

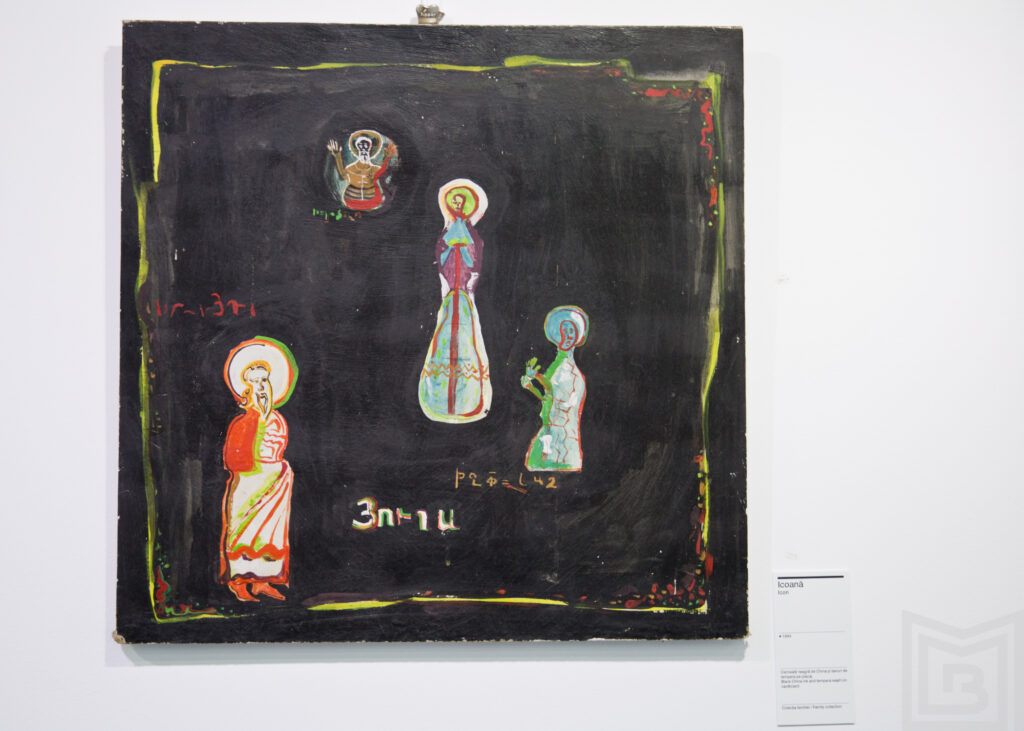

Until the 14th of November, visitors of the Nicolae Minovici Museum in Bucharest could view some of Ecaterina Vrana’s paintings as part of an exhibition reuniting works from several private collections. The Romanian artist (1969-2019) has exhibited works in various countries and was recognized for the style of her paintings, mixing image and text to form pictures which could be considered visual diary fragments.

The exhibition was held in an underground gallery in the garden of the neo-Romanesque style house turned museum, built in 1905, on the then outskirts of Bucharest. Visitors could find the exhibition room while walking on the stone paths leading to the orchard, after visiting the permanent ethnographic collection hosted inside, containing various landscape paintings, traditional Romanian costumes, pottery pieces, and family photos from the last century.

Ecaterina Vrana with Chicken Army, 2016. Photo by Veronica Kirchner.

The impression of the paintings being a visual diary is strengthened by the appearance of sketches of Ecaterina Vrana‘s works. The artist aims to convey a certain mental state spontaneously, for which the recurrence is important. Even though the Surrealists, for example, aimed at showing the subconscious in its raw state, any painting requires certain preparation, the more so if it is to depict the world of dreams. Ecaterina Vrana renounces this pretension, even though her creating process is anchored in it and emanates a surrealist feeling. Her painted dreams do not aim to convince or engulf the viewer, they simply are the outward manifestation of the artist’s need of expression. The viewer is excluded from the process, just as a diary is not intended to bring clarifications to anyone else.

What unites the paintings and shows that they are a whole are the recurring motifs which the artist combines in various ways, in order to convey feelings. What results is a coded language of forms which only the creator can understand. That doesn’t mean, though, that onlookers can’t share in their profound intimacy. They can form their own connections of the different signs, explore their own inner universe and, at the same time, get a feeling of the meaning they had for the artist when she used them, because they convey universal experiences or biographical ones, as it is in one of the paintings in the exhibition, Waiting for the Doctors, completed in 2018, where the artist tries to convey the suffering caused by her disease.

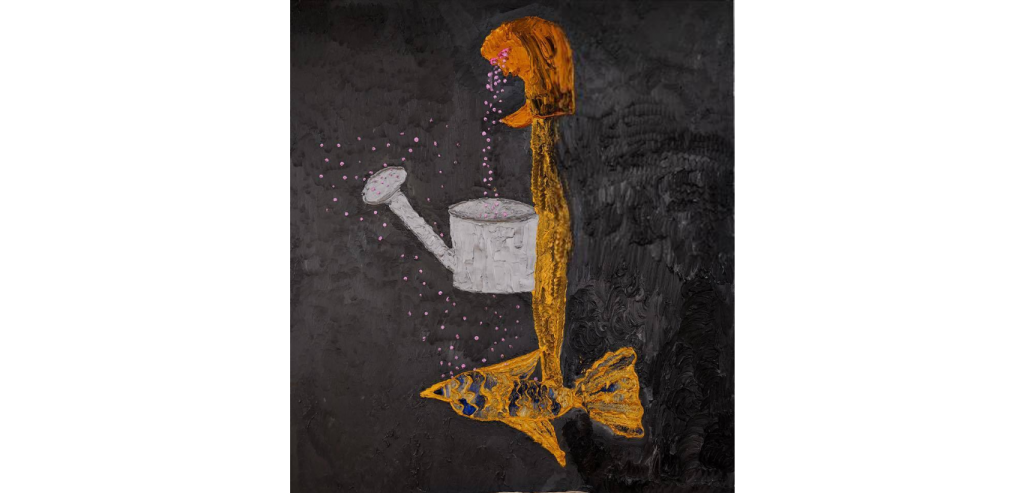

Ecaterina Vrana, Self Portrait with Watering Can, 2015, Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Ecaterina Vrana, Pain of the Shoe, 2015, Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Some of the symbols the artist uses are women in gowns, a chicken, a watering can, fish, shoes, kisses, and knives, which appear on the canvas as if they were letters, multiplied, of different dimensions and colors. The preoccupation for exactness is left behind in the process of obtaining a form of language. In the recurrence of signs, though not in their manner of representation, Ecaterina Vrana’s paintings are linked to those of female surrealist painters such as Remedios Varo or Dorothea Tanning.

The fact that painting is the equivalent of diary keeping could be seen also in the fact that often, the artist considered her works finished when having added text to them: fragments of phrases that mark the day or certain mental states. Often, much of the painting is occupied by the background, which could be considered a page where the imaginary visual and the actual language combine to form something akin to a poem of forms. It reminds, from this point of view, the visual poems of Christian Morgenstern, such as Fisches Nachtgesang (Fish’s Night Song) and transgresses the two domains in a kind of symbiosis (the painting couldn’t sometimes be complete without the writing, but it wouldn’t be enough for the artist to keep a separate diary and discuss other things in her works).

Ecaterina Vrana, Pain of the Shoe, 2015, Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

The lack of details and the broad backgrounds reminds one of the manner of another Romanian painter, Constantin Piliuta, whose work was exhibited most recently in September during the 2021 “Art Safari” temporary exhibition. His works are based likewise on outlines, sketches, and recurring themes. In this sense, the series of approximately 10 self-portraits is noteworthy, as well as the many paintings depicting winter landscapes composed of white background interrupted by small houses seen from aerial view. Here is another common point, as Ecaterina Vrana’s works also include self-portraits suffused with the same subjectivity common to all her paintings.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!