Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

From the 17th to the 19th century, art academies across Europe and America excluded women from their classrooms. Only a few of them count as exceptions. These women artists went against sexist rules and fought to be considered as equals to their male peers. Let us look at some of these women in art academies.

Before the 17th century, if someone wanted to be an artist, they would enter a workshop to learn the craft—this was the guild system. Once they learned everything they needed, artists moved on and established their own workshop to receive commissions and train apprentices. However, in the 17th century, academies spread throughout Europe to unify artistic education. In these new schools, every student followed the same curriculum as their peers and learned from the same teachers. This way, painting and sculpture acquired the coveted title of “liberal” (intellectual) arts. Artists were now considered professional, learned men, above artisans. Even though the guilds survived for decades, the Academies grew in importance across Europe.

This new status of painters and sculptors excluded women, who were considered intellectually inferior to men. Part of the reasoning was a supposed care for their reputation; the academies put great emphasis on drawing from life, which meant lessons with naked models. It would have been terrible, socially, for women students to remain in the presence of such a scene. But, if they did not know anatomy, they could not paint realistic human figures. Thus, they could not create history paintings (mythological, religious, historic scenes), the highest-regarded genre. It was a vicious cycle that kept women away from critical acclaim. Most of them could only focus on genre scenes, landscapes, still life, and portraits if they were lucky. In the eyes of the Academy, those were lesser and “easier” genres.

Regardless, some women artists managed to enter the academies and have successful careers.

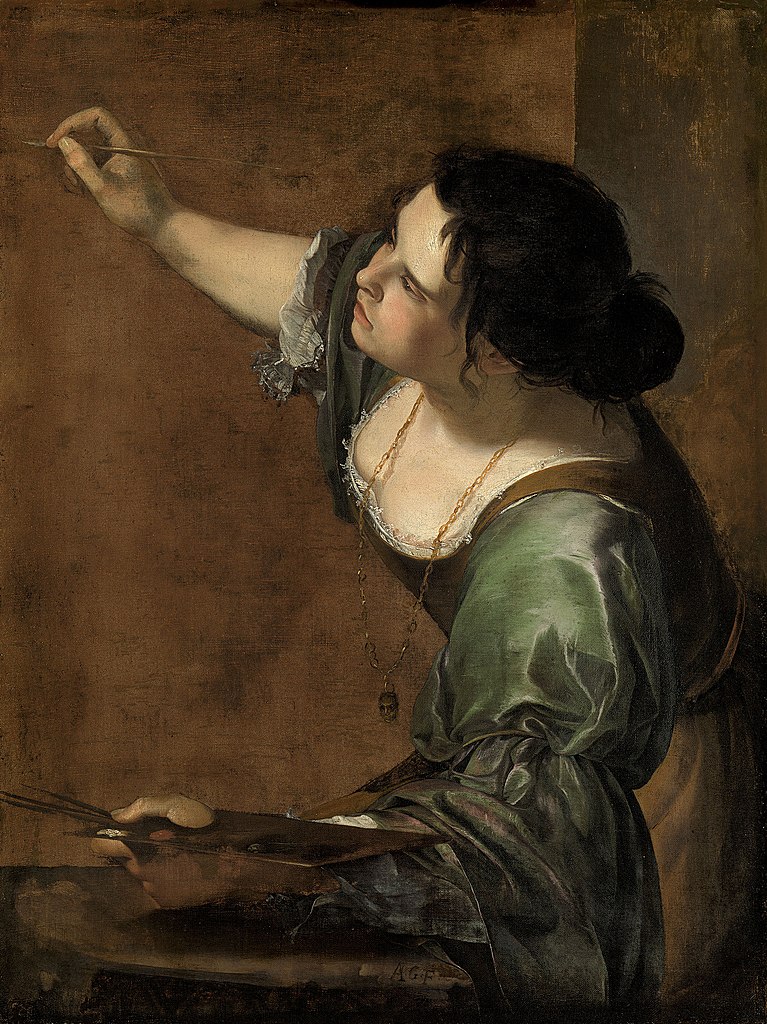

Italian art academies from the Renaissance served as models for the later ones. Since Italy was not yet unified, several city-states established these schools independently. Florence had the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno since 1562. In 1583, Rome established the Accademia di San Luca. In 1607, it allowed women to become members, but restrictions to the classes and meetings remained. Therefore, women relied on male relatives or family friends to teach them and cultivate their skills before proving their talent to the academicians. Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) got into the Florentine academy in 1616.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, 1638-1639, Hampton Court Palace, London, UK.

Similarly, Bologna built an academy at the beginning of the 18th century, also with restrictions on women. In consequence, Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) established her own independent academy where she taught women students.

Elisabetta Sirani, Self-Portrait, 1658, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia.

The first great academy was the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) in Paris, France, established in 1648. Technically, it did not prohibit admission to women, but its requirements did not give them many opportunities. Every aspiring student had to present a piece to prove their talents. This meant applicants already needed a degree of education that most women did not have access to, especially anatomical knowledge. In total, only 14 women studied at the Royal Academy from 1663 to 1793. They are now remembered as some of the most famous female artists.

Nicolas Loir, Minerva and the Arts. Allegory of the Foundation of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture also known as Progress of the Arts of Drawing in France under the reign of Louis XIV, 17th century, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

After the Revolution, the new government replaced the Royal Academy with the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts). This one did not admit women until 1897. Other smaller, more local schools like the Académie de Julian admitted women. However, the tuition was more expensive than that of men and with a limited curriculum.

The second most important academy was the Royal Academy of Arts in London. King George III established it in 1768. Out of the 38 founding members, only two were women: Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and Mary Moser (1744-1819). Queen Charlotte supported their careers, which helped them become part of that founding group. The painting below, however, by Johan Zoffany illustrates how the two women were also excluded still. Since the scene takes place in a life drawing class with a naked model, he could not paint Kauffman and Moser there. He depicted them in two portraits at the top right.

Johan Joseph Zoffany, The Portraits of the Academicians of the Royal Academy, 1771-1772, Royal Collection, London, UK.

An argument can be made that all of these advances happened when the institutions were in crisis. As we reached the end of the 19th century, modernism replaced the academic style. At this point, even if women got access to these schools, they would not have the same level of importance as they would the century prior.

Perhaps you know some of these artists already. Today, they are some of the most famous women artists, precisely because there is a record of their work in a formal institution. Women in art academies accessed important social circles to form connections that helped them professionally.

Academic Art, Art Encyclopedia. Accessed: 17 Jan 2024.

Acquisition du portrait de Catherine Duchemin, Château de Versailles website. Accessed: 17 Jan 2024.

Elizabeth Cheron, Brooklyn Museum’s website. Accessed: 17 Jan 2024.

Octave Fidière, Les femmes artistes à l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, 1885, BnF Gallica. Accessed: 17 Jan 2024.

Royal Academy of Arts, Women and the Royal Academy of Arts, Google Arts & Culture. Accessed: 17 Jan 2024.

Ursula Tania Estrada López: “The Entrance of Women to the Art Academies in Brazil and Mexico: a Comparative Overview”, (in 19&20), 2015, DezenoveVinte. Accessed: 17 Jan 2024.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!