5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know

The purpose of art for a group of avant-garde individuals at the turn of the 20th century was no longer the realistic rendition of the natural world,...

Guest Profile 29 February 2024

“Illness, madness, and death were the black angels that watched over my cradle and have since followed me through life,” Munch wrote in his notes, almost as an explanation for all the death-related motifs that were to form a significant part of his pictorial world. He presented the death literally in the series of images of his mother and sister and metaphorically, as a skeleton who is usually dominated by even more evil women. Life and death, love and terror, the feeling of loneliness—all of them were depicted through strong lines, dark colors, somber tones, and an exaggerated form. We found the most horrifying depictions of death from Munch’s oeuvre.

Edvard Munch had two close encounters with death in his childhood which left a huge mark on his life. His mother died of tuberculosis in 1868 and so did Munch’s favorite sister Johanne Sophie in 1877. It left ineradicable traces on his soul, but it also laid the foundation for a number of his major works.

This painting is exceptional among the others depicting death. The skeleton is calmly sitting at the helm of the old man’s boat. It steers his life and the lives of the men in the boats from the second plane—steers to inexorable deadly destiny.

Munch believed that woman symbolized man’s loss of power as she had come out of him, as a “vampire” that sucked the vitality out of him. Here is a woman, who looks like death, and is probably trying to suck the life out of a powerless man.

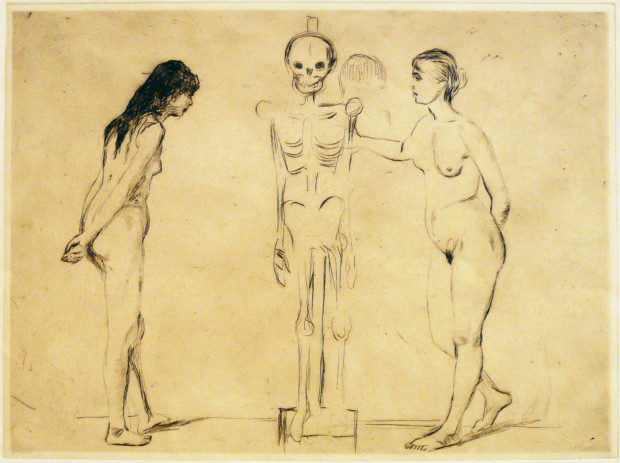

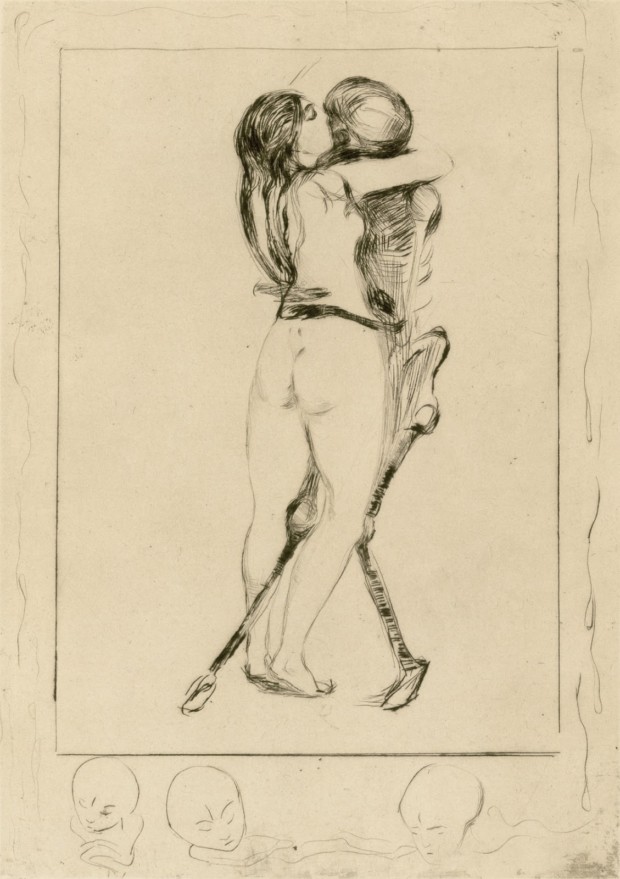

Munch found the inspiration for this kind of motif in the literary community in Berlin, which was dominated by August Strindberg and Stanisław Przybyszewski. This can be a kind of variation on the theme “dance of death“, dating from the late Middle Ages. It showed a procession or dance of the living and the dead and usually symbolized death’s presence in life and its power over human life.

Starting in 1899, Munch had an intimate relationship with a “liberated” upper-class woman, Tulla Larsen. This stormy relationship lasted until 1902, when Munch injured two of his finger during an accidental shooting in the presence of Larsen, who had returned to him for a brief reconciliation. She finally left him and married a younger colleague of Munch. Munch felt betrayed and painted two different compositions, with The Death of Marat he wanted to show female perfidy. The story of Marat’s murder by Charlotte Corday, in my opinion, bears no resemblance to that of Munch and Tulla Larsen, but evidently it was enough for Munch’s symbol-stretching mind. We can see a nude Munch lying on a bed, blood dripping from his wounded hand, which is equivalent to Marat dying in his bath. Nearby stands a nude Larsen, an erect frontal figure with her accomplished deed behind her. She replaces the upright packing-case in Jacques-Louis David’s picture.

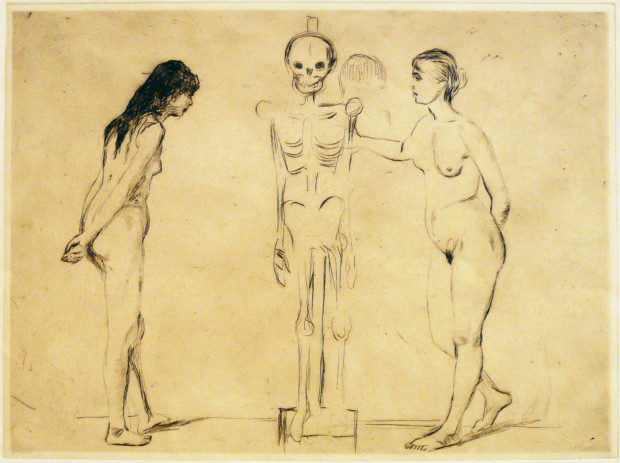

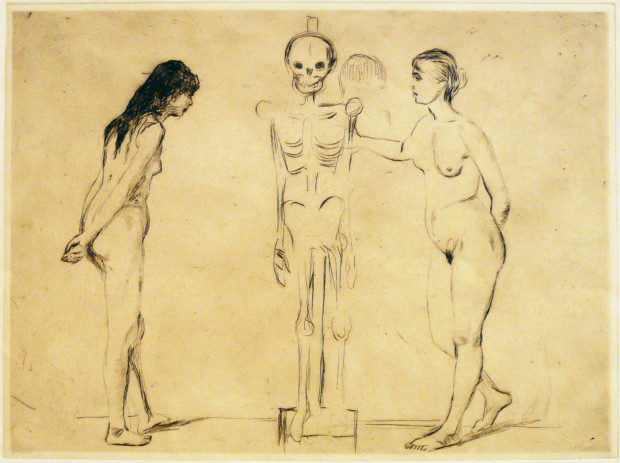

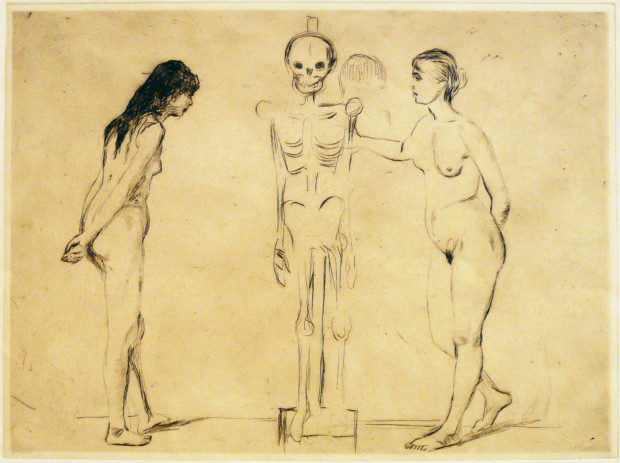

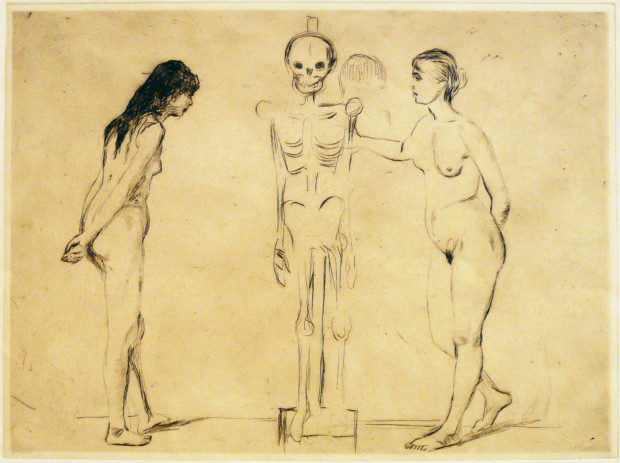

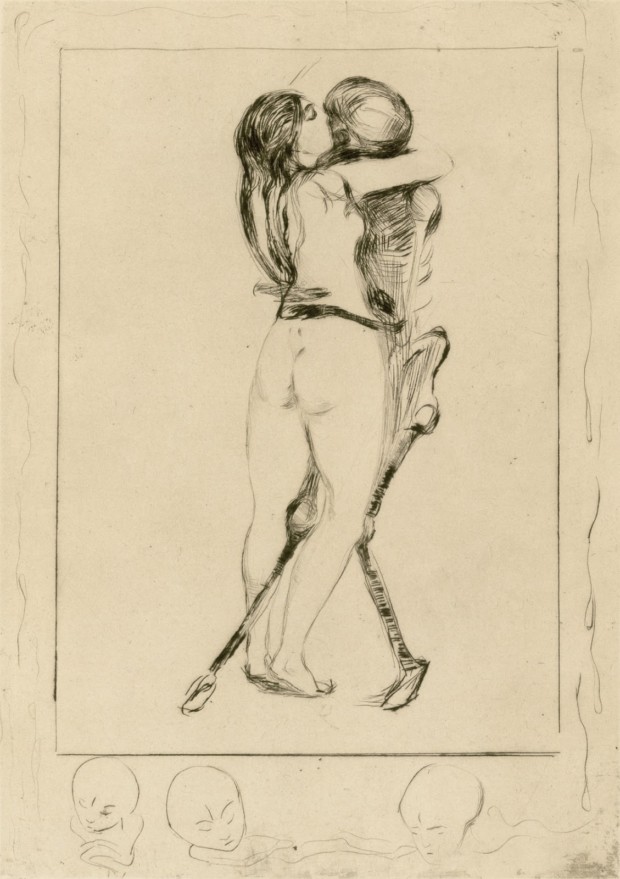

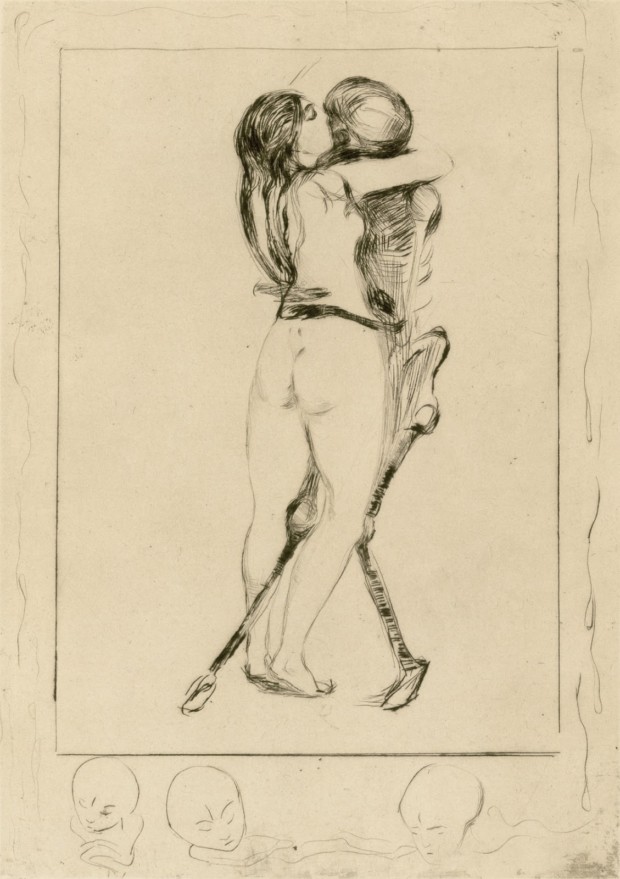

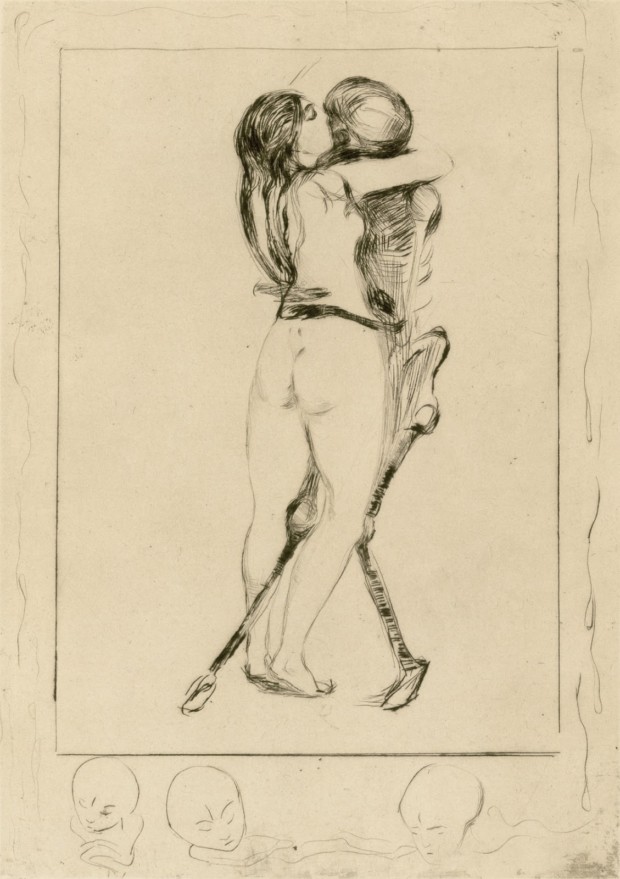

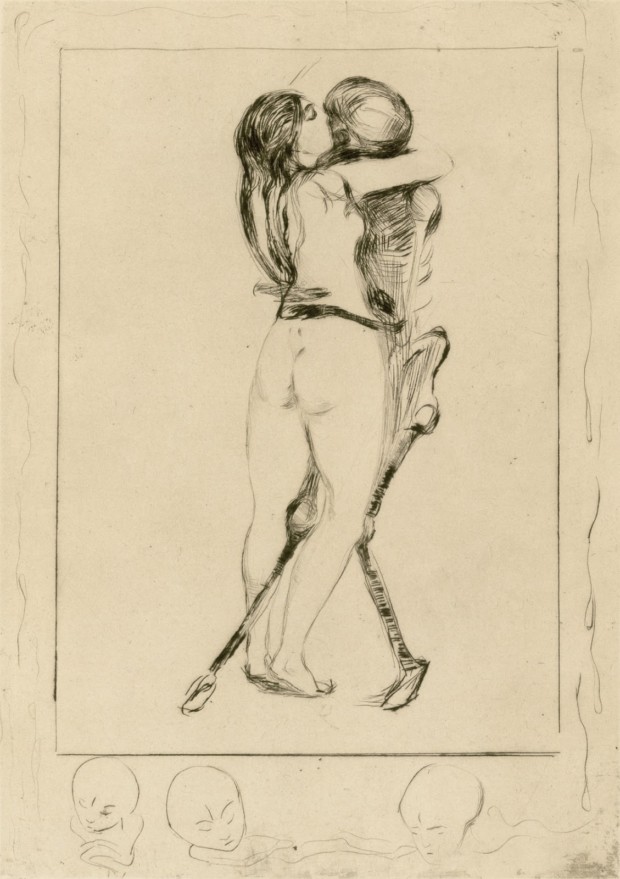

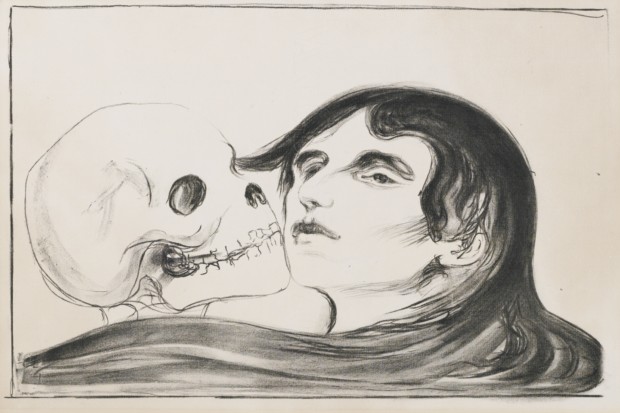

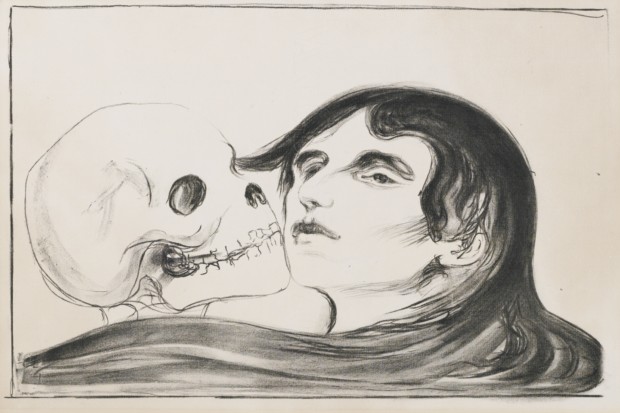

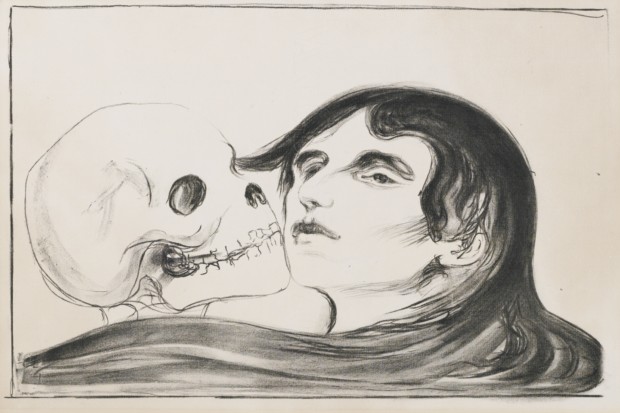

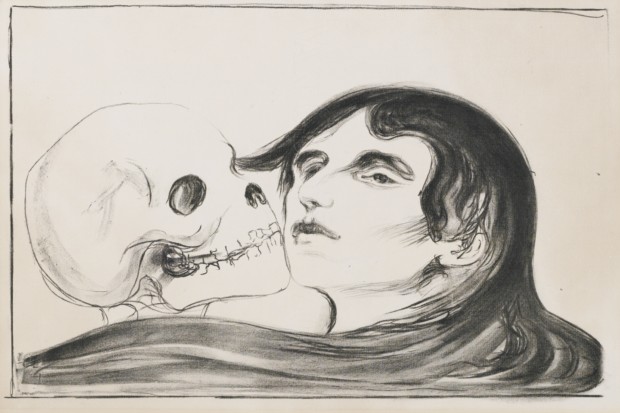

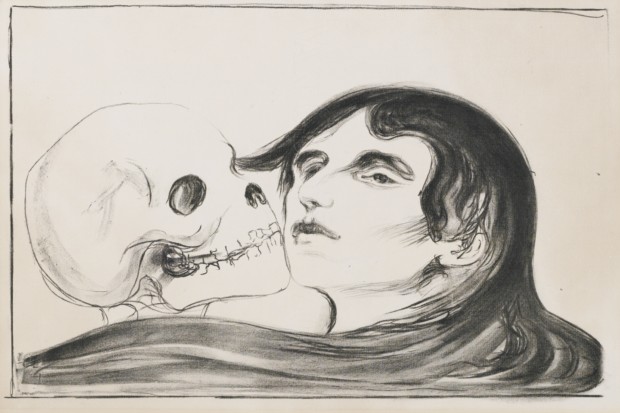

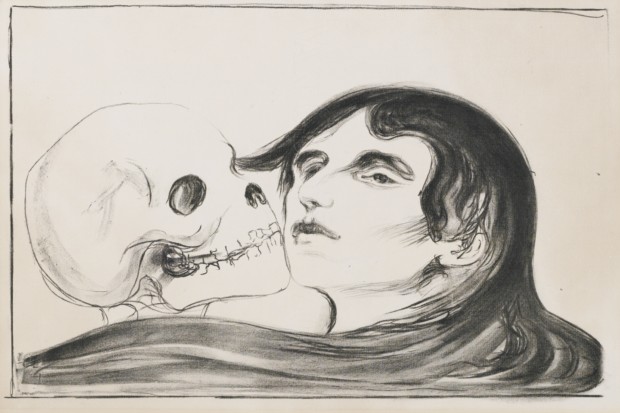

Edvard Munch completed this engraving in 1894, one year after the original oil painting. Here, death is a skeleton; no flesh covers it anymore. In this work Munch does not conform to traditional representations of the theme that reaches back to the 15th century. At the beginning of the Renaissance, death was often represented in a sexually aggressive way. In this engraving, Munch suggests a victory of love over death: the girl is not dominated by death, she embraces it with passion.

In this work the young girl looks similar to the one previously shown in Death and the Maiden. Her long hair covers the neck and the shoulders of death, who sweetly kisses her cheek. She, however, remains indifferent to him and looks away with forlorn eyes. Once again, the maiden seems to dominate her partner.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!