Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

27 March 2024 min Read

Elena Luksch-Makowsky was a trailblazing painter and sculptor whose work traversed the cultural landscapes of St. Petersburg, Vienna, and Hamburg. In this article, we delve into the life, influences, and enduring legacy of this remarkable artist, exploring how her creative vision evolved amidst the vibrant art scenes of these iconic European cities. Join us as we unravel the threads of Luksch-Makowsky’s artistic tapestry, from her early beginnings to her lasting impact on the art world.

Elena Konstantinova Makovskaya was born in 1878 in St. Petersburg to an aristocratic family of artists. Her uncle Vladimir and her father Konstantin Makovsky were members of the Russian artist’s group known as Peredvizhniki (“Wanderers”). The Wanderer’s inspirations were everyday Russian life and history, as well as scenes from Russian mythology and fairy tales.

Elena’s upbringing was a preparation for her future role as a wife, mother, and homemaker, but her talent could not go unnoticed. Her father encouraged her in many ways to develop her talent. In 1889 she set off on a trip around Europe with her mother and her siblings. Later it turned out to be a very helpful event for Elena.

In 1895 Elena began her preliminary studies in the private studio of Ilya Repin. At the time Repin was at the top of his success. A year later he accepted Elena into his master class at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. This was not unusual as women were permitted as students in the Academy from 1893. Additionally, she attended a sculpture class taught by Vladimir Beeklemishev. One can easily see that in this period the rural Russian character has a great influence on Elena’s work.

Johann von Bloch, a Polish banker, noticed Elena’s work at one of the regular Academy exhibitions. He offered her a scholarship to travel abroad. She chose Munich. In Munich, Elena studied in Anton Ažbe’s school. From there she moved on to study in Schloss Deutenhofen under Mathias Gasteiger’s supervision. In works from this period, the influence of the Dachau artist’s colony is evident.

Elena Luksch-Makowsky was growing as an artist but also as a person. She developed her unique style. At the time she nurtured a tomboyish look, wearing her full red hair loose, with a red beret. She was striving for “male” freedom. Even in her marriage she clearly defined her wills and needs. She had a written agreement with her future husband Richard Luksch that she could visit Russia whenever she wanted without his approval. Another important thing for her was that they continued to work as independent artists.

Elena married Richard Luksch, an Austrian painter and sculptor, in June 1900. After that, they moved to Vienna, where they both engaged in the Vienna Secession. Elena regularly took part in their exhibitions until the split in 1905. She was the only female artist with her own Vienna Secession monogram, but she didn’t have the right to vote. However, her artistic abilities were impressive. She participated in their exhibitions shoulder-to-shoulder with male colleagues such as Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffman.

Her best-known works, Ver Sacrum and Adolescentia, were central pieces in the 1902 and 1903 exhibitions. Furthermore, her equal status in the group affirmed the design of an entire issue of the Secession Journal “Ver Sacrum”.

Russian tradition was a central theme for Elena. She took up typical Russian subjects and merged them into a new artistic entity using the visual language of Jugendstil. This approach places her among the artists associated with the artistic group called Mir iskusstva (‘World of Art’). The so-called miriskusstniki rejected the rigid rules of academic painting and realism of the past generation of painters. Their shared points of view were a neo-romantic cult devoted to the beauty of “old Russia”, a focus on arts and crafts, and a preference for ornamental and stylized forms in the Western style.

Luksch-Makowsky knew some of the so-called miriskusstniki. For example, Igor Grabar arranged for her to participate in the fourth exhibition of the journal “Mir iskusstva” in 1902.

Elena and Richard were both involved in the design and furnishing of the Joseff Hoffmann’s Stoclet Palace in Brussels, viewed by many as the architectural climax of the Vienna Workshop. In 1907 Richard Luksch took a job as a professor at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg. Therefore, the Luksch-Makowsky couple moved there. It was a great loss for the artistic scene in Vienna.

After arriving in Hamburg they continued their relationship with Vienna, particularly with the Vienna Workshop. The couple participated in the art show in the Austrian capital in 1908. In this period significant transformation of Luksch-Makowsky’s style occurred. The filigree lines of Vienna are significantly simplified and strengthened and the colors become stronger and more vivid.

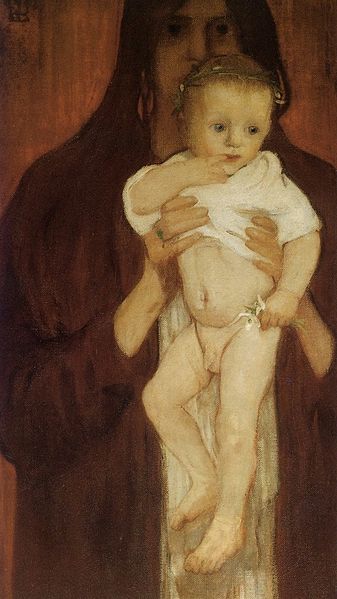

Elena Luksch-Makowsky continued to maintain close ties with Vienna and St. Petersburg. As opposed to her husband, it was very hard for her to integrate herself into Hamburg’s society and art circles. In this period she made Women’s Fate. The work Women’s Fate was the culmination of her long personal battle with the relationship between life as an artist and the role of motherhood. It is also one of her greatest masterpieces.

What Elena feared early on happened in 1921 when she got divorced from Richard. This left her solely responsible for her three young sons. As a result, she couldn’t fully concentrate on her artistic work. Her work situation was also less secure with the assumption of the National Socialists’ power. In 1934, she joined the Reich Chamber of the Fine Arts but the hoped-for increase in public assignments did not come.

Even so, Luksch-Makowsky remained true to her visual style, which was no longer in accord with popular tastes. Works completed during this period are either lost or hard to find. After WWII she largely produced religious icons and decorations for the Russian Orthodox congregation in Hamburg, where she died on August 15, 1967.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!