Pioneer of Italian Fashion: Artist-Designer Rosa Genoni

An Italian artist-designer at the turn of the 20th century, Rosa Genoni is described as a founder of Italian fashion, a dressmaker, a teacher, a...

Nikolina Konjevod 13 May 2024

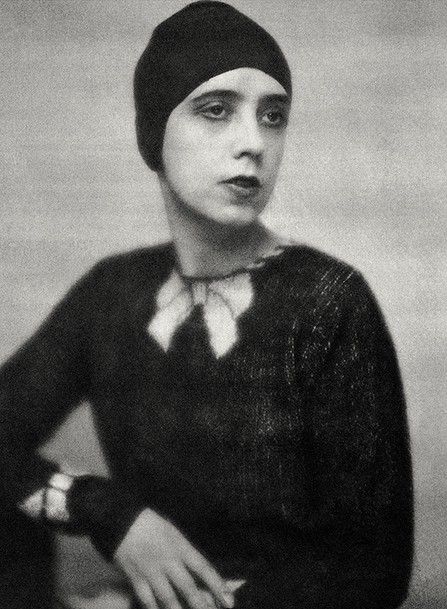

Italian female fashion designer and couturier, the greatest rival of Coco Chanel, and a friend of Surrealists such as Salvador Dalì and Man Ray, Elsa Schiaparelli became one of the most prominent figures in fashion and art between the two World Wars by turning the fabric into a painting canvas.

She opened her eyes for the first time on September 10th, 1890 in the capital of Italy, Rome. Her parents gave her the name Elsa. When she was young, she studied philosophy at the University of Rome and wrote poems in her free time (the contents of which shocked her conservative family). Since she came from an aristocratic family, Schiaparelli led a refined life with a certain amount of luxury provided by her parents’ wealth and social status. When Schiaparelli reached the age of 22, she left for London where she accepted a job as a nanny.

During her stay in London, she spent most of her free time visiting various museums, attending lectures, and there she got in touch with spiritualism, theosophy, and oriental philosophies. In 1914, she attended a lecture given by Count Wilhelm de Wendt de Kerlor. Schiaparelli fell in love and married him against her parents’ wishes and they moved to his family home in Nice. Afterward, they lived in Paris, Cannes, Monte Carlo, and later moved to New York in 1916.

Elsa Schiaparelli removed herself from a life of luxury because she was convinced that it had precluded her from creativity and art. Onboard a ship during the transatlantic crossing to America, she became friends with Gabrielle Picabia, wife of the Dadaist painter Francis Picabia. Schiaparelli’s interest in the Dada and Surrealist movements and her friendship with Gabrielle Picabia facilitated their entry into the creative and artistic circle of New York, which comprised noteworthy members such as Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Steichen.

In 1922, Schiaparelli left New York and moved back to Paris where she assisted Man Ray with his Dada magazine Société Anonyme and met the famous couturier and one of the fathers of modern fashion Paul Poiret who influenced her future design and fashion career. With the encouragement of Poiret, she started her own business, but in 1926 her house closed due to financial difficulties.

After her initial failure, the year 1927 was a turning point in Schiaparelli’s career. She launched a new collection of knitwear using a special double-layered stitch and sweaters with Surrealist trompe l’oeil images. In the same year, she also appeared in Vogue. However, her first iconic piece, a faux-bow sweater, was the item that helped launch her career and brought her style to the masses.

Schiaparelli was not the only one of the first designers to use a visible zipper in haute couture but also one of the first couturiers to develop the wrap dress, later revisited and perfected by the American designer Diane von Fürstenberg in the 1970s.

In 1928, the Pour le Sport collection expanded into bathing suits, ski-wear, and linen dresses. The couturier designed the first jupe-culotte, a divided skirt, worn by famous Spanish female tennis star Lilí Álvarez.

Along with her success, the Schiap Shop, which initially focused on sportswear, in the 1930s would turn into a recognized brand of urban living and nightlife when Elsa Schiaparelli added to her collection evening wear. She created her first evening dress with a jacket, which during Prohibition in the United States provided a hidden pocket for a flask for alcoholic beverages.

In 1934, Schiaparelli decided to add a millinery department to her business. One of her iconic hat designs at that time was a so-called “mad cap’” worn by celebrities like Katharine Hepburn. Since the hat design had been copied by many contemporary fashion designers, Schiaparelli ordered every single mad cap to be destroyed.

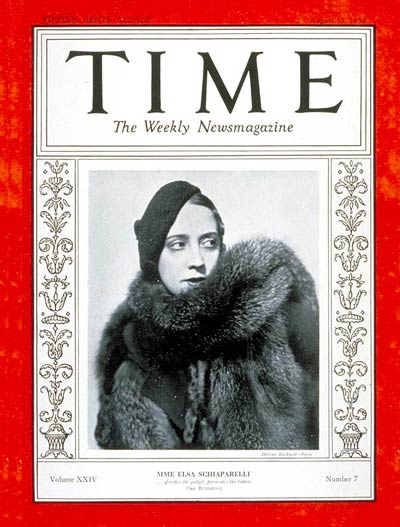

Her designs became so popular worldwide that in 1934 Time Magazine dedicated a cover to her, presenting her as one of the arbiters of ultra-modern haute couture. Schiaparelli became the first female fashion designer to be honored on the cover of Time.

In 1935, when Schiaparelli visited Amsterdam, she noticed local women wearing a newspaper on their hats. The fashion idea was born and she created the first newspaper print fabric.

After the Time’s recognition, she began an active collaboration with the Spanish Surrealist painter Salvador Dalì. In 1935, they designed a perfume together shaped like a telephone dial, an actual telephone with a fake lobster on it, and in 1937, the famous Shoe hat, which was worn by Dalì’s wife, Gala. The inspiration for the shoe hat came from a photograph of Dalì with his wife’s slipper on his head. Thanks to Dalì’s participation in her designs, many famous actresses and important female figures of the time wore Schiaparelli’s dresses like Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, wearing the Lobster Dress on her honeymoon.

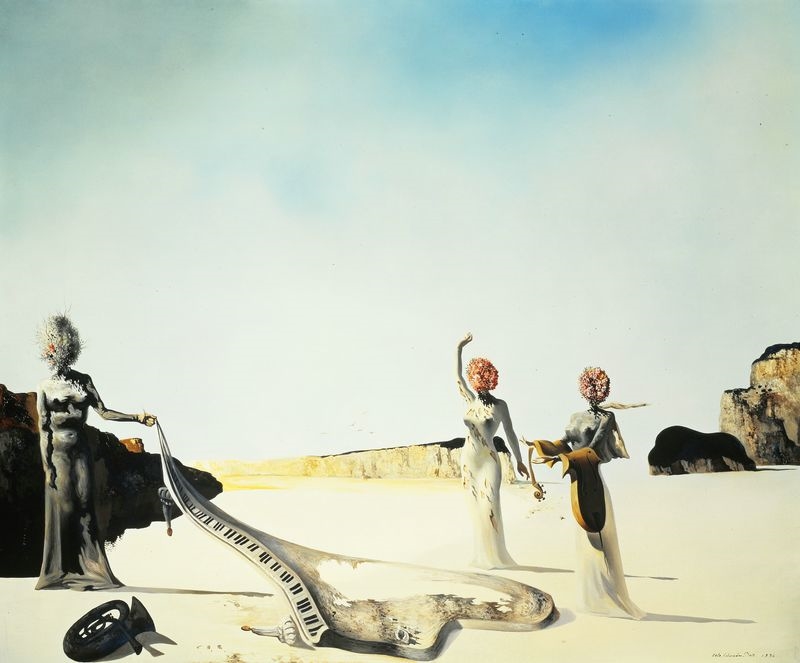

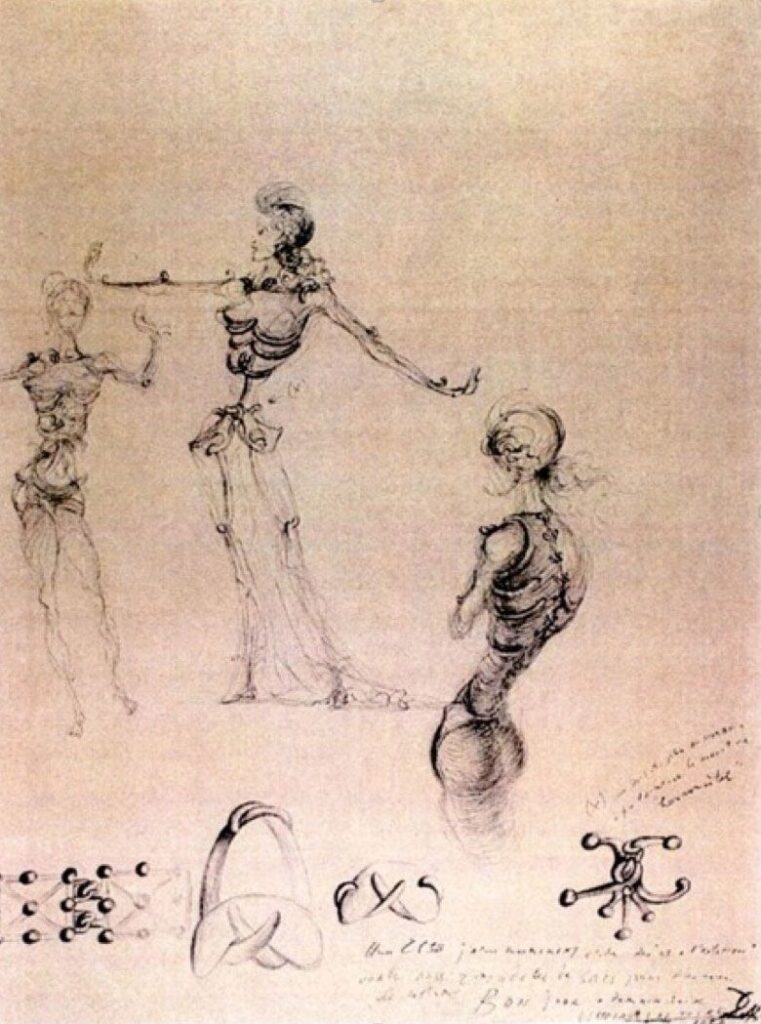

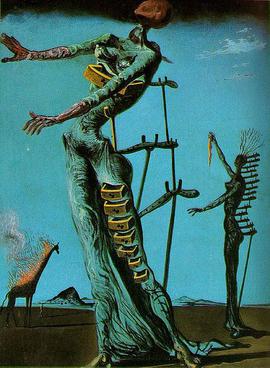

The collaboration between these two artists brought to life another iconic fashion piece called Tears Dress as a reference to some of Dalì’s own previous works like Three young surrealist women holding in their arms skins of an orchestra (1936). In this painting, Dalì depicted women with flayed or torn flesh and the exact image has been put on the fabric. Tear Dress is a part of the Circus Collection created and presented by Schiaparelli in 1938. Many critics believe that the dress functions as a memento mori, as a response to the Spanish Civil War and the spread of Fascism.

Schiaparelli’s Skeleton Dress from the same year was also created in conjunction with Salvador Dalì and it references his own exploration of the skeletal form, which he often depicted in paintings and works of art around this time. The dress is also part of the Circus Collection and for its production, a special quilting technique called trapunto was used. The disturbing image of the skeleton itself serves as a symbol of the ongoing Second World War and a reminder of the victims who were suffering from famine.

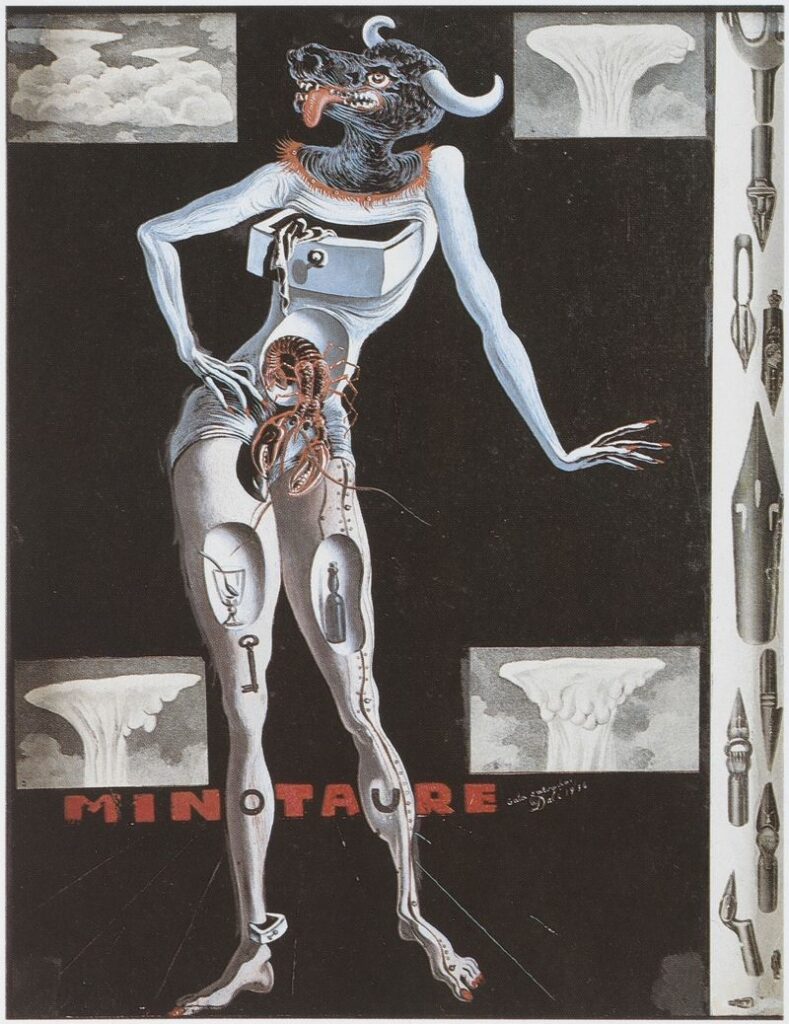

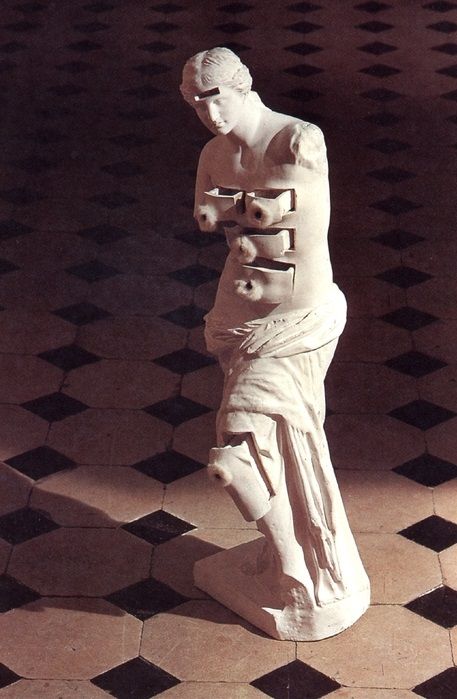

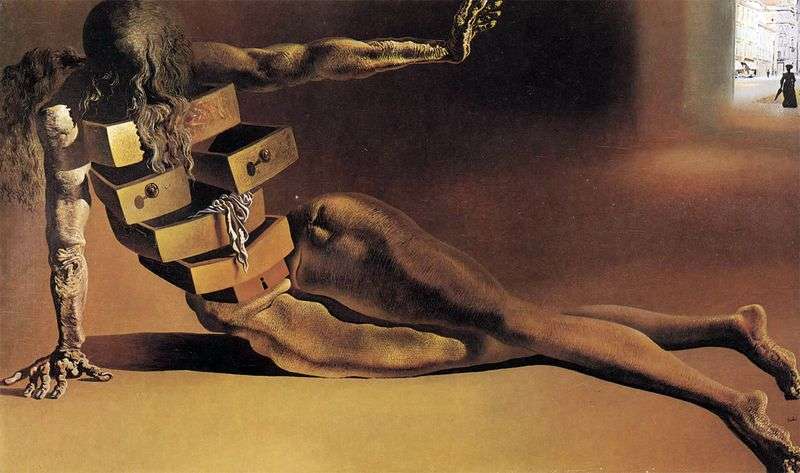

Schiaparelli and Dalì also presented a collection of suits with drawers pockets on them. In the same way as Schiaparelli was obsessed with pockets in her fashion designs, Dalì in many of his paintings used the drawers to reference the subconscious. In the Cecil Beaton photograph, we can see that the model is holding a copy of Minotaure, the surrealist journal, making a significant connection.

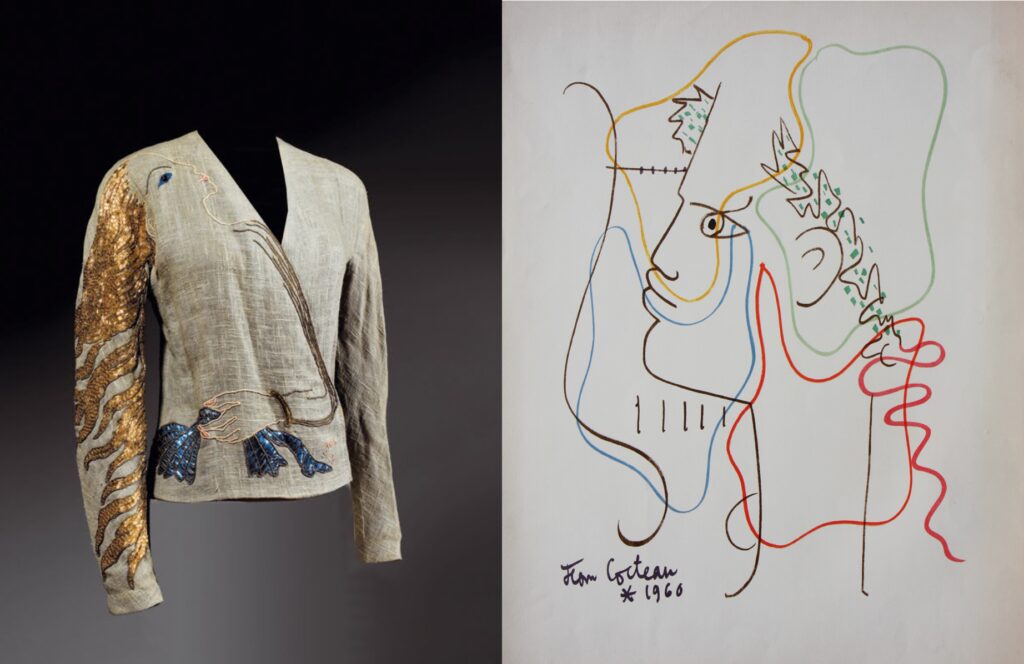

In 1937, in collaboration with French avant-garde poet Jean Cocteau, Schiaparelli designed clothing masterpieces such as an evening coat featuring two trompe l’oeil faces and roses, a trademark of her style. Collaborations with famous artists such as Dali and Cocteau generated some of Schiaparelli’s most renowned pieces. In the second picture, we can see two faces lining together and creating a vase.

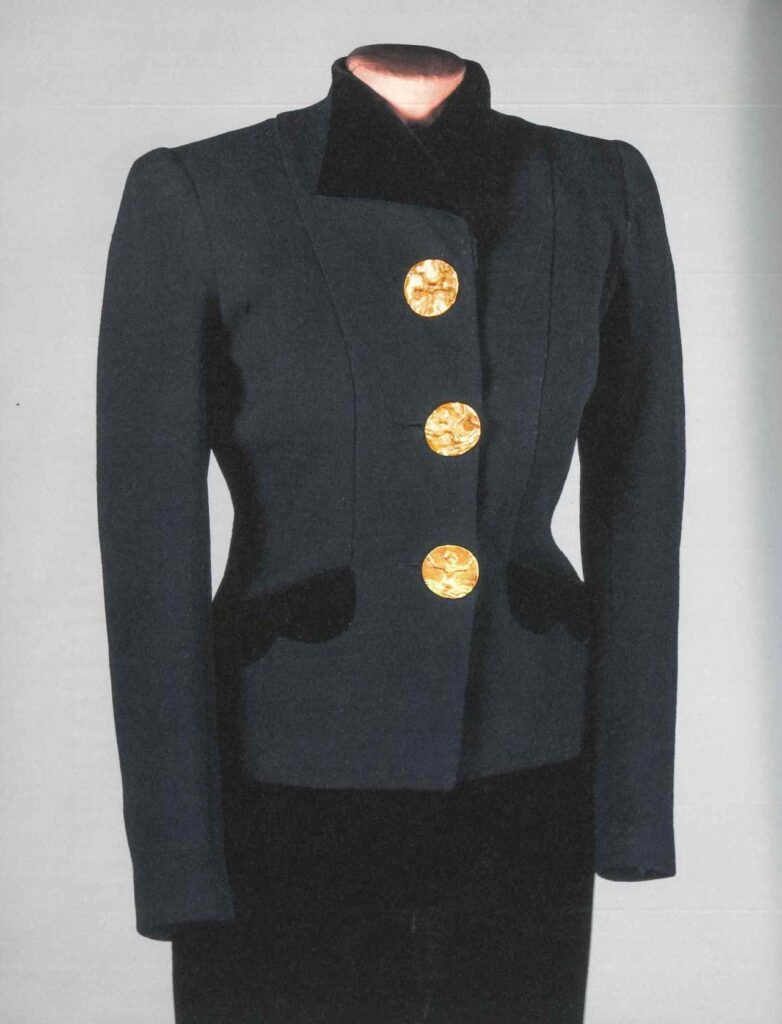

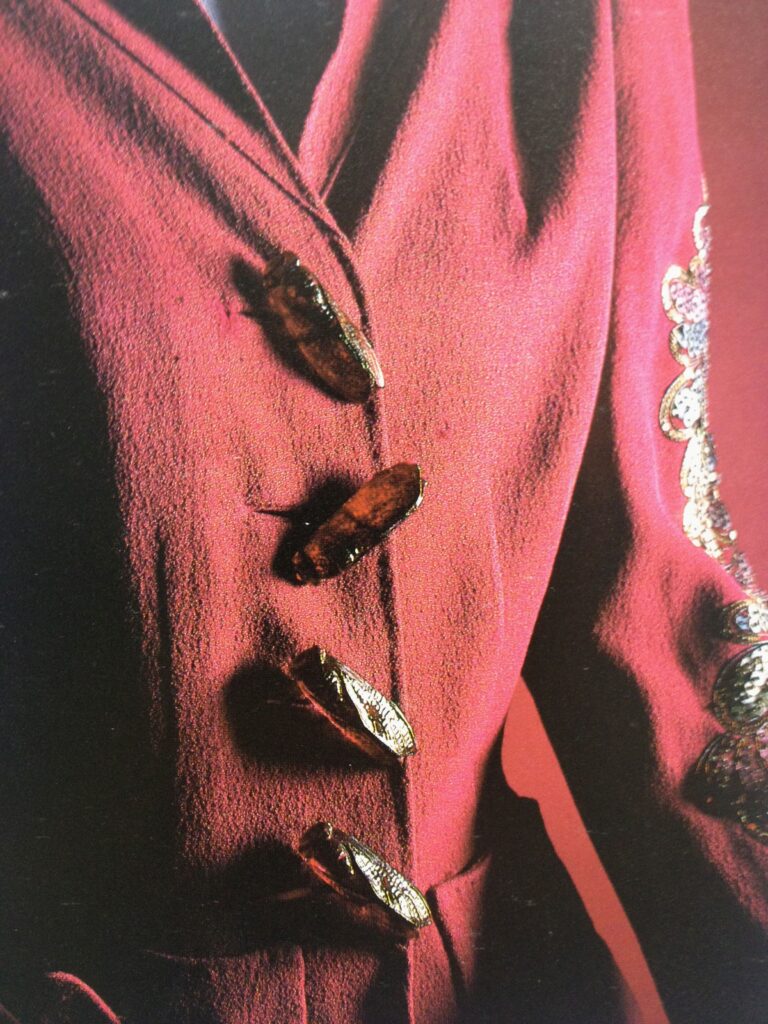

Schiaparelli was also known for her use of unusual buttons, which often resembled candlesticks, playing cards, ships, crowns, mirrors, or even crickets. In 1938 and 1939, she collaborated with the famous Italian sculptor Alberto Giacometti to create bronze buttons featuring sirens.

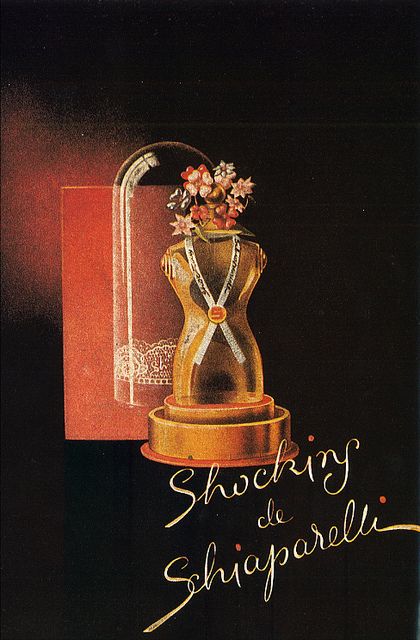

In the same year, Schiaparelli launched her perfume called ‘Shocking’ along with her signature color as many fashion designers or artists did and do to this day – the shocking pink– the color she described in her world as:

Life-giving, like all the light and the birds and the fish in the world put together, a color of China and Peru but not of the West

– Elsa Schiaparelli, Maison Schiaparelli.

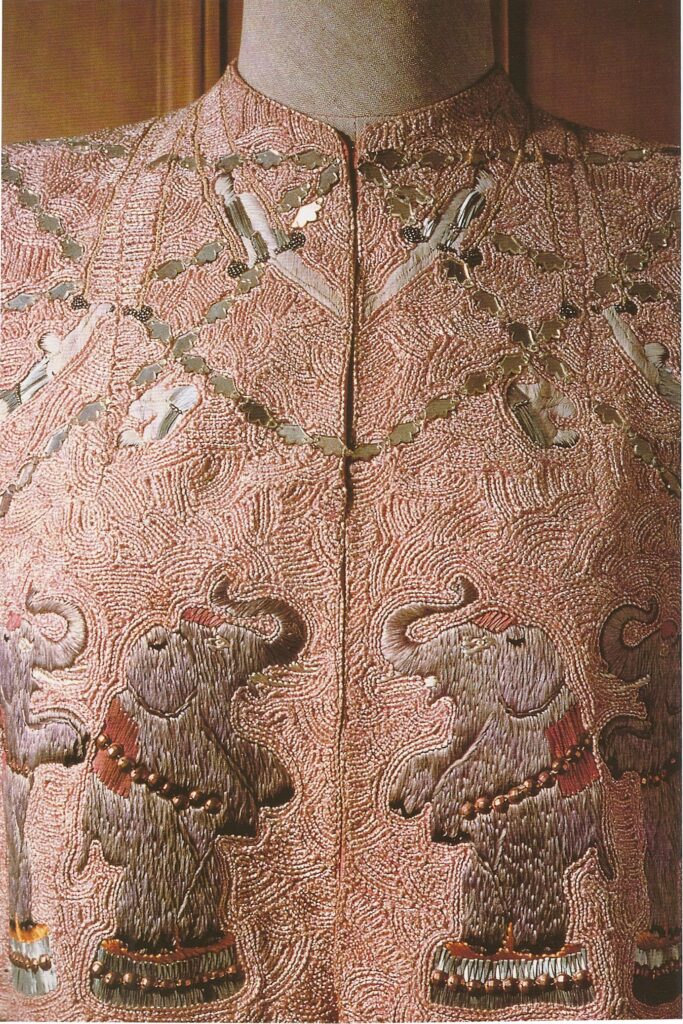

Schiaparelli’s pre-war collections, from 1938 to 1941, are dedicated to the circus, Commedia dell’arte, and fruit. The one collection that I found particularly interesting is her 1938 Circus Collection, where customized buttons, detailed embroidery, and prints were developed especially for the collection. Schiaparelli commissioned many custom pendants and brooches from French jeweler Jean Schlumberger, who is best known for his work at Tiffany & Co.

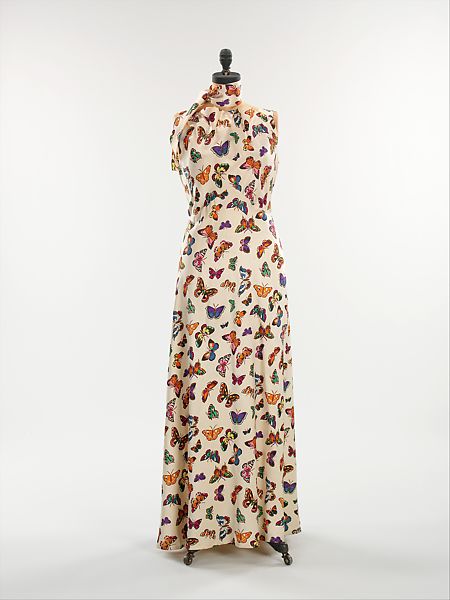

It was still in the mid-century when Schiaparelli launched another of her collections focused on a particular animal kingdom: insects. Yes, exactly, those little creatures which usually appear on our clothing during the summer, something so natural to be part of Schiaparelli’s creative expression.

With Schiaparelli’s designs, many of her gloves are incredibly memorable and often transcend our idea of what a glove can be. She produced suede gloves in both black and white, with red snakeskin fingernails to replicate human hands. These playful gloves were created around the same time Picasso painted hands to look like gloves for a Man Ray photo and Schiaparelli obviously was inspired by this. She also created claw gloves resembling an image of a cat woman or a fauve and the evening gloves evoking a submarine world and mermaids.

A few years later, a Surrealist artist appeared who created very similar designs for gloves inspired by Schiaparelli’s collection: Her name was Meret Oppenheim. In Oppenheim’s artworks, whether we are talking about gloves or not, we can see that the artist is consciously blurring the line between body and clothing. The perfect example is silk-screened leather gloves or fur gloves with wooden fingers.

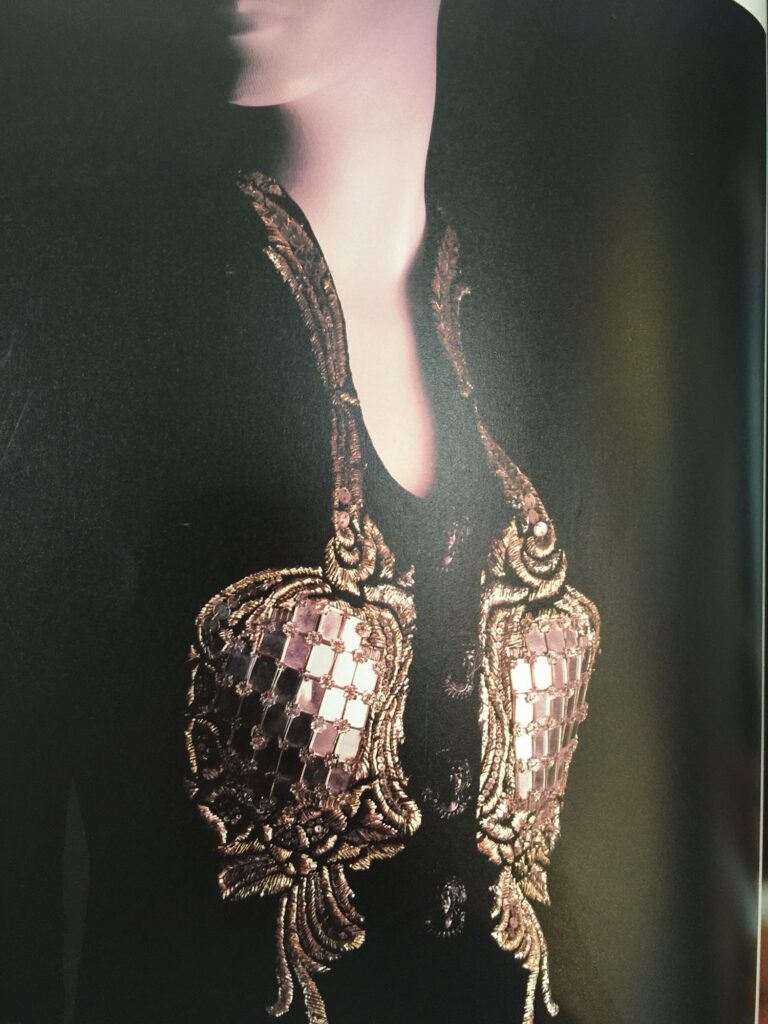

Schiaparelli was constantly playing games with and teasing her viewers. Mirrors on this suit from 1938-39 are positioned strategically and symbolize a man’s confrontation with himself. Anyone who puts his view on the bust of the woman wearing this coat is confronted by his own image. With this design, Schiaparelli recognized and critiqued the way in which women were framed in position in society in the late 1930s.

In 1939, when France declared war on Germany, Schiaparelli was forced to leave Paris and, from 1941 on, she spent the war years in New York. After the war, she returned to France and restarted her activity but her business started to wind down, not only because of her rivalry with Coco Chanel but above all because of the emergence of Christian Dior’s New Look.

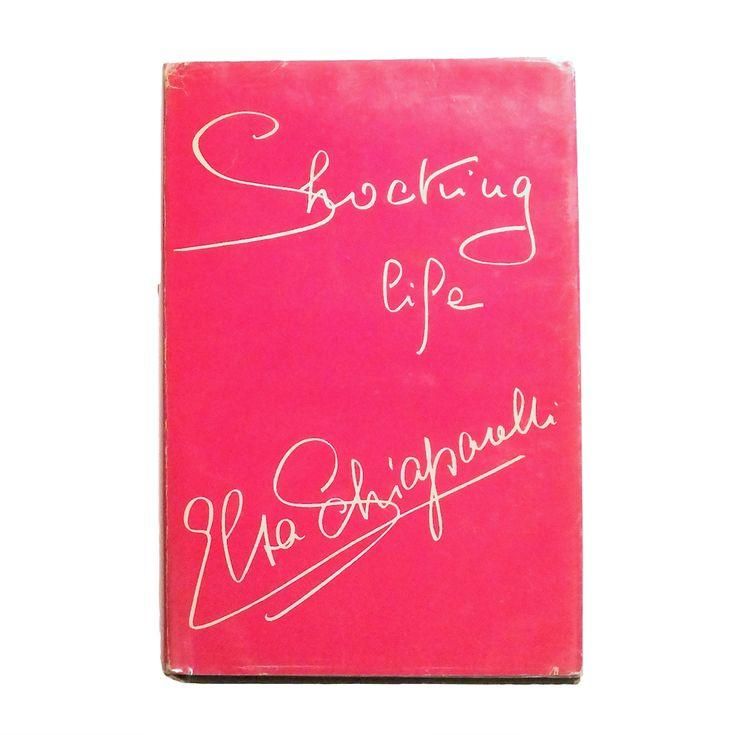

The house of Schiaparelli ended its activities in December 1954, the same year that her great rival Coco Chanel returned to the business. Schiaparelli spent a comfortable retirement living in Paris and wrote her own autobiography entitled Shocking Life. After her death in 1973, her shop in Paris reopened only in 2012 at the same address, in Place Vendôme, and is now a leading brand in haute couture.

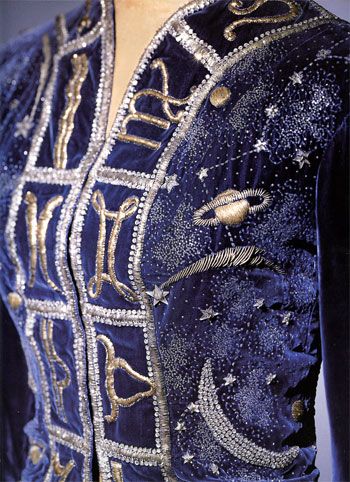

In Fall/Winter 1980, Yves Saint Laurent created the Collection Shakespeare to pay tribute to literature by using references to various poets in a surrealistic manner. As part of the collection, St. Laurent showed a blue velvet jacket embroidered with a pair of eyes and the French words: Les Yeux d’Elsa. Translated as “The Eyes of Elsa”, the words are the title of a poem by Louis Aragon. However, with this jacket, St. Laurent also cleverly makes an homage to Schiaparelli by taking inspiration from her Zodiac Collection of 1938-39.

As much an artist as a dress designer, Schiaparelli developed her revolutionary style in designing clothing by building on the inspiration of Futurism, Surrealism, and the radical style of the couturier Paul Poiret. Her vision of fashion as a visual art influenced all of her work, from the creation of her Shocking Pink, to her gowns featuring pictorial artworks of Surrealists painters like Mirò or Salvador Dalì. Distilling their disquieting dream-based imaginary and provocative concepts through her own creative process, she incorporated themes inspired by contemporary events, erotic fantasy, traditional and avant-garde art, and her own psyché into her designs.

Thanks to Elsa Schiaparelli’s revolutionary ideas, controversial designs, and fashion collaborations with Surrealists who put art and fashion on the same level, her haute couture became synonymous with art masterpieces and equally as art represents a symbolic language, that goes beyond the ephemeral and contingent value of a specific use or trend. Schiaparelli’s unforgettable designs aspire to transcend time and become art that is everlasting.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!