5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

13 August 2022 min Read

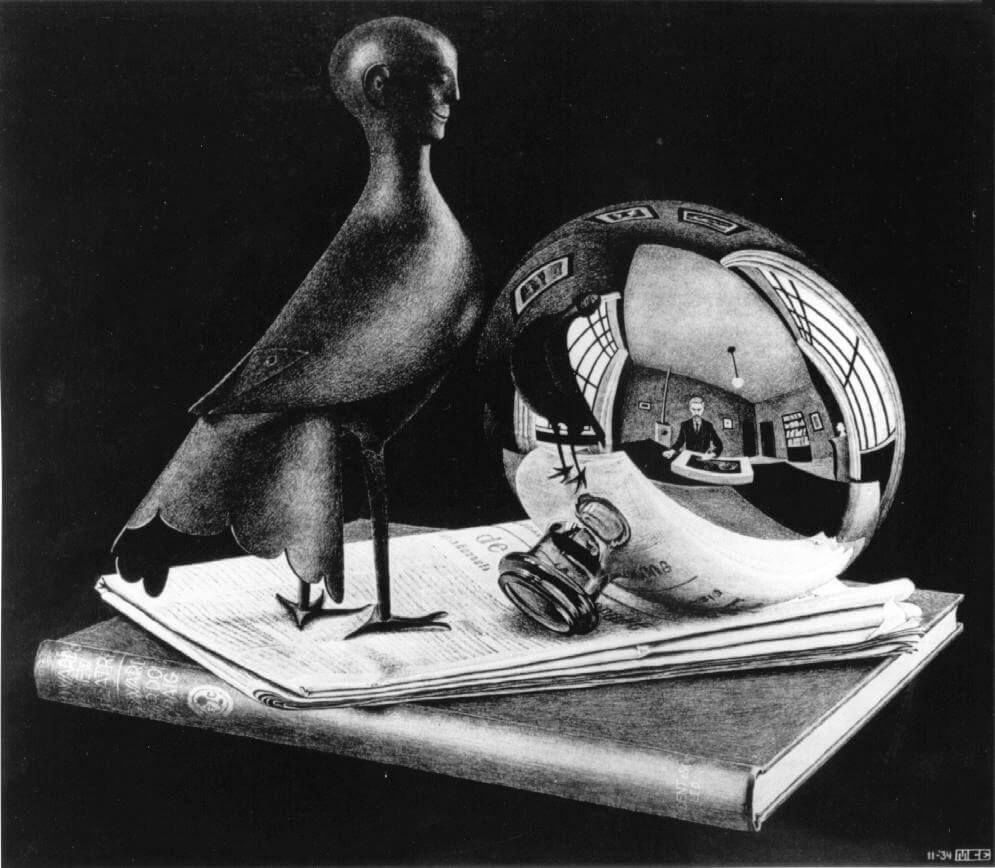

Known for representing impossible constructions and creating a world in which the figurative and the abstract intertwine, meet Maurits Cornelis Escher. This artist was also known for his mathematical fixation and for the geometric and symmetrical forms of his illustrations which can be visually challenging. Are you ready?

M.C. Escher was born on June 17, 1898, in Leeuwarden. His father was an engineer, which perhaps explains the many representations of architecture in the artist’s work.

Little “Mauk”, as he was known to friends and family, did not do very well in school. Even despite studying in a special school because he was a sickly child, he never achieved high grades. Nevertheless, he excelled in drawing classes.

In 1919, Escher entered the College of Architecture but illness hindered his success in academic life again. This time he suffered from a skin disease. Escher transferred to a decorative arts course and with the experience he gained in drawing and woodcut classes, he left the faculty in 1922. He then went to travel through Italy and Spain. It seems that this change paid off as his travels provided him with numerous influences that would permeate his work from that point on. He also met the love of his life in Italy, Jetta Umiker, whom he married in 1924.

Escher can be considered one of the best representatives of op art as he was an expert at creating illusions through the volumes and shapes he included in his illustrations. It was after his visit to Spain, still in the 1920s, that Islamic mosaics and their geometric patterns charmed him. He then tried to incorporate them into his own works.

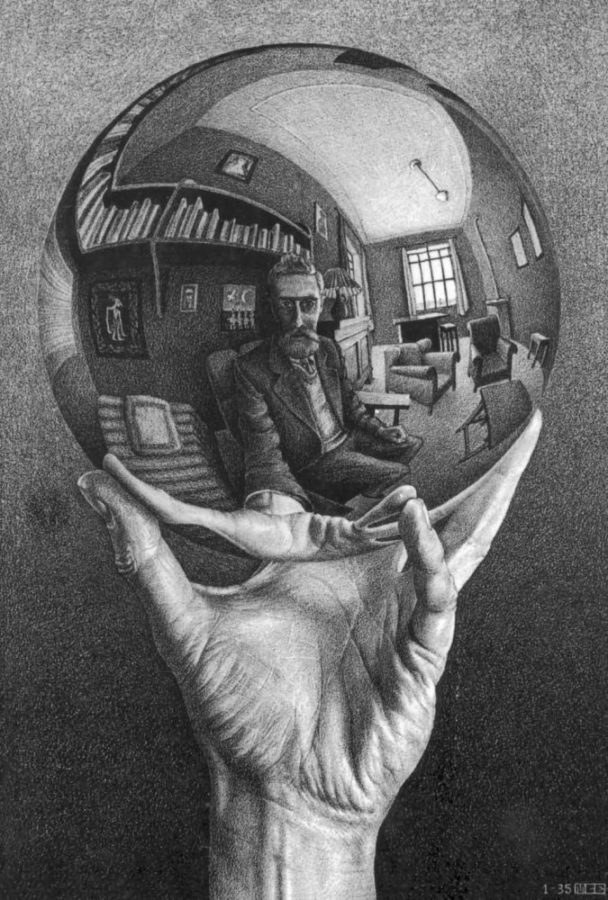

Hand with Reflecting Sphere (above) is a self-portrait. Escher holds the sphere that reflects his face, easily recognized by the thick beard the artist wore. The way he holds the ball, as well as the position of the image, reminds me of the way we hold our cell phones to take “selfies” nowadays. More than a self-portrait, this image is also a reflection (and this is not a pun) because, besides showing himself as normally happens in self-portraits, the artist actually sees himself.

In 1935, the year in which this illustration was made, things were not going so well in Italy, at that time led by Mussolini. Escher, who generally took no interest in current affairs, decided to move to Switzerland with his family after his eldest son, George, was forced to wear the Opera Nazionale Ballila uniform at school. Unfortunately the artist was very unhappy after their move as he was accustomed to Italy and very fond of living there.

Escher’s work shows much of the Surrealism and Expressionism that marked the first half of the 20th century. Two years after moving to Switzerland with his family, Escher spent time in Belgium and then went to the Netherlands, where he lived until 1970.

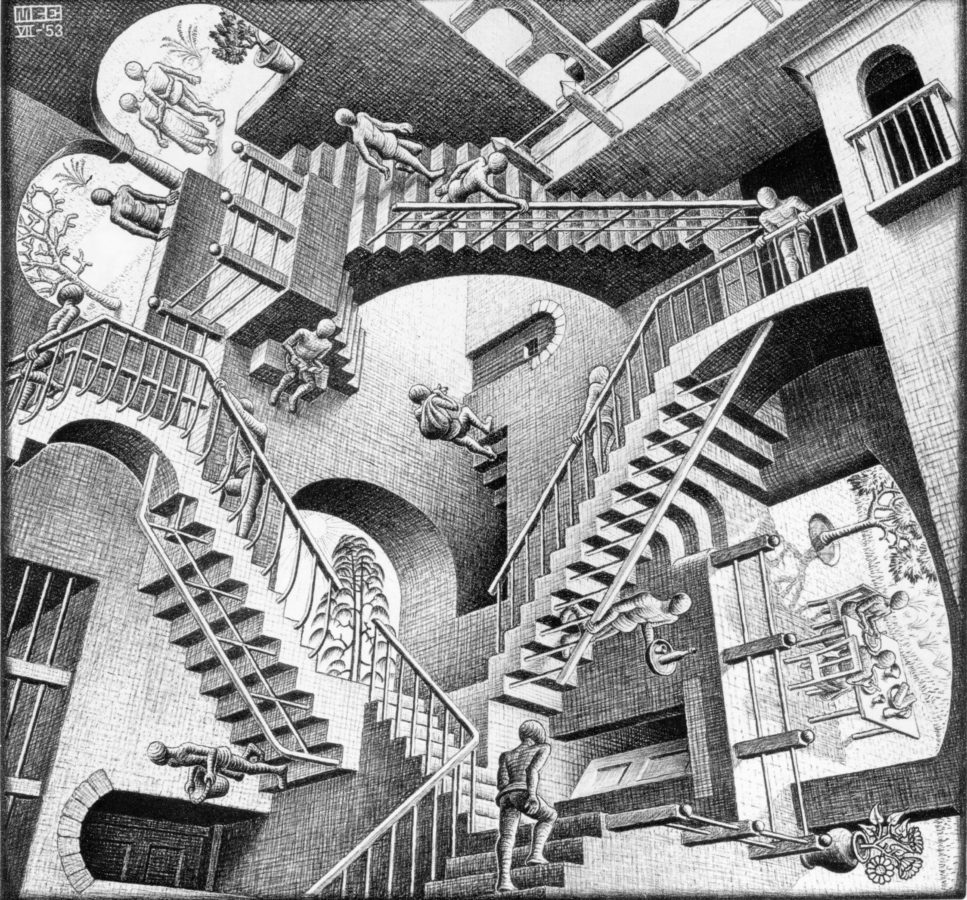

In Relativity (above), Escher presents a world in which the Laws of Gravity make no sense. In fact, a world where nothing, apparently, makes sense. People float by the margins of the illustration, stairs are placed in impossible areas, and doors appear almost out of nowhere. It is a chaotic de-construction, a symbol of something that Escher once said: “We adore chaos because we love to produce order”. And he produced order within the very chaos of this drawing.

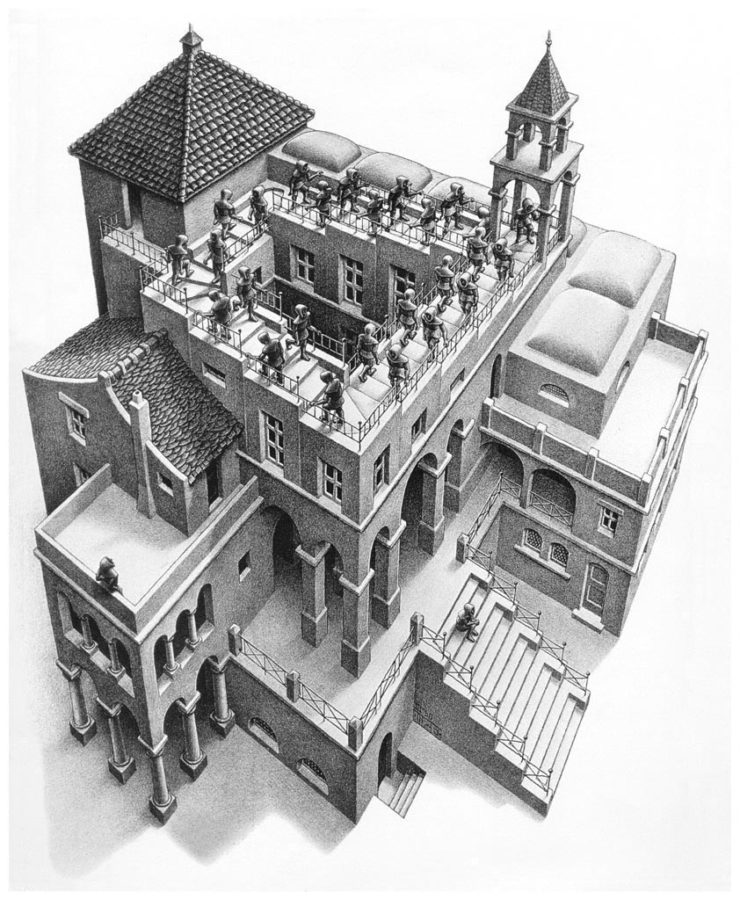

In Ascending and Descending (below) one might think, where do the stairs bring us? Where are these people going from/to? Let your gaze play (or not) with this enigmatic work, simultaneously an infinite descent and an infinite ascent. How can one not be enchanted by it?

In 1972, a few months before his 73rd birthday, Maurits Cornelis Escher died at the Hilversum Hospital. The artist already had health problems and had even undergone surgery a few years before. Since beginning his work in the 1920s, Escher only took one hiatus in his artistic career, in 1962, due to health problems. Hundreds of illustrations compose his work (no paintings) and are loaded with mysterious sensations and surrealist approaches.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!