5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

24 April 2023 min Read

This post will be tough because abstraction is tough. And so is often modern art. In this article, I will try to explain a radical Russian avant-garde abstract art movement—Suprematism—and introduce you to its pioneer Kazimir Malevich. Suprematism is one of these movements which produced artworks that make people ask “why is it called art? My little brother would paint it better.” But trust me, Suprematism is an art movement that definitely has something to say. Please open your eyes and hearts and look at what we have for you here:

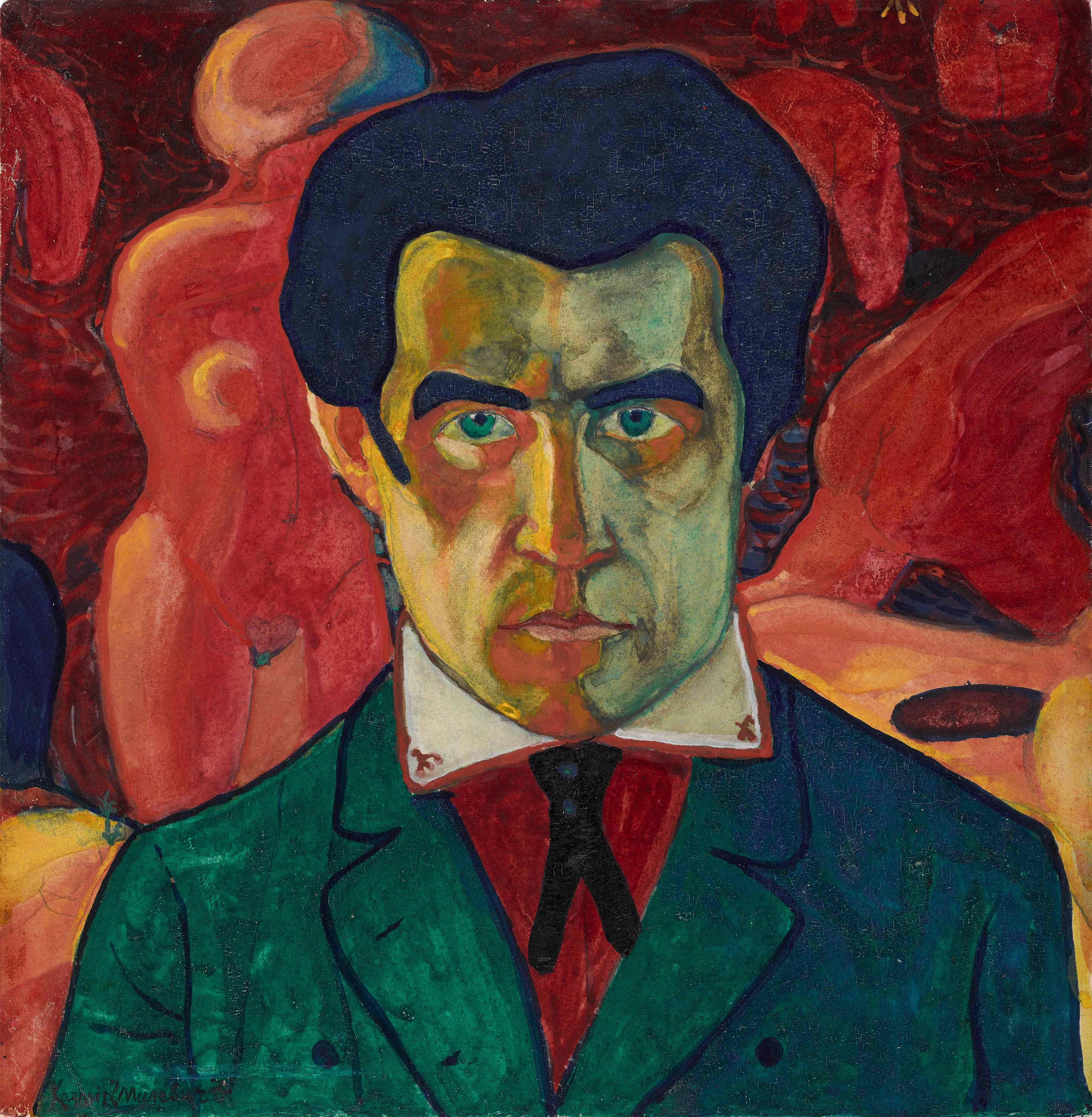

Kazimir Malevich, Self-portrait, 1910, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The pioneer of Suprematism was the artist Kazimir Malevich who was born in Kyiv (then part of the Russian Empire) to Polish parents. The Suprematists wanted to define the boundaries of art reaching the “zero degree” – a point beyond which art would cease to be art. To achieve this they used simple motifs, such as shapes like squares, circles, crosses, and flat surfaces with plain fields of color. Such practice was meant to encourage the viewers to focus on their sensations during seeing art.

Suprematism derived its name from Malevich’s belief in the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.” Moreover, the artist believed that Suprematist art would be superior to all the art of the past. This approach, introduced after World War I, during tumultuous political times in Russia, was very radical. Affected by the rise of avant-garde and Russian Formalism, it was all about feeling and getting away from the previous art movements.

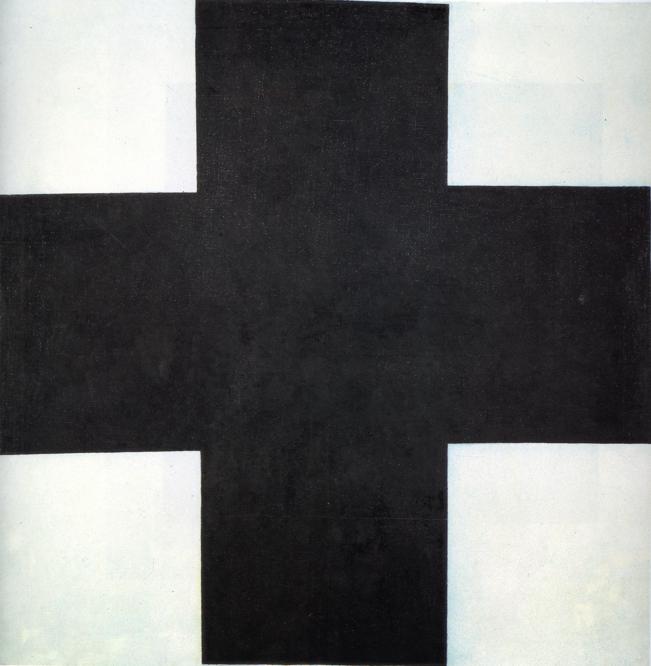

This is the most important piece in the history of Suprematism, and one of the most important in the history of modern art. Malevich had an idea that art could make us look at the world in new ways, and could transform reality. He removed the iconography of the real world entirely and left the viewer facing the work to contemplate what kind of picture of the world is in front of him.

The ugliness of the stronger ones was brought almost to a vanishing point but did not go beyond the frames of zero. But I transformed into zero of form and went beyond 0 – 1.

Kazimir Malevich, The manifesto released for the Last Futuristic Exhibition of Paintings: 0.10 (zero ten), St. Petersburg, Russia: Matyushin, 1915, trans. Dominique Volkovynska.

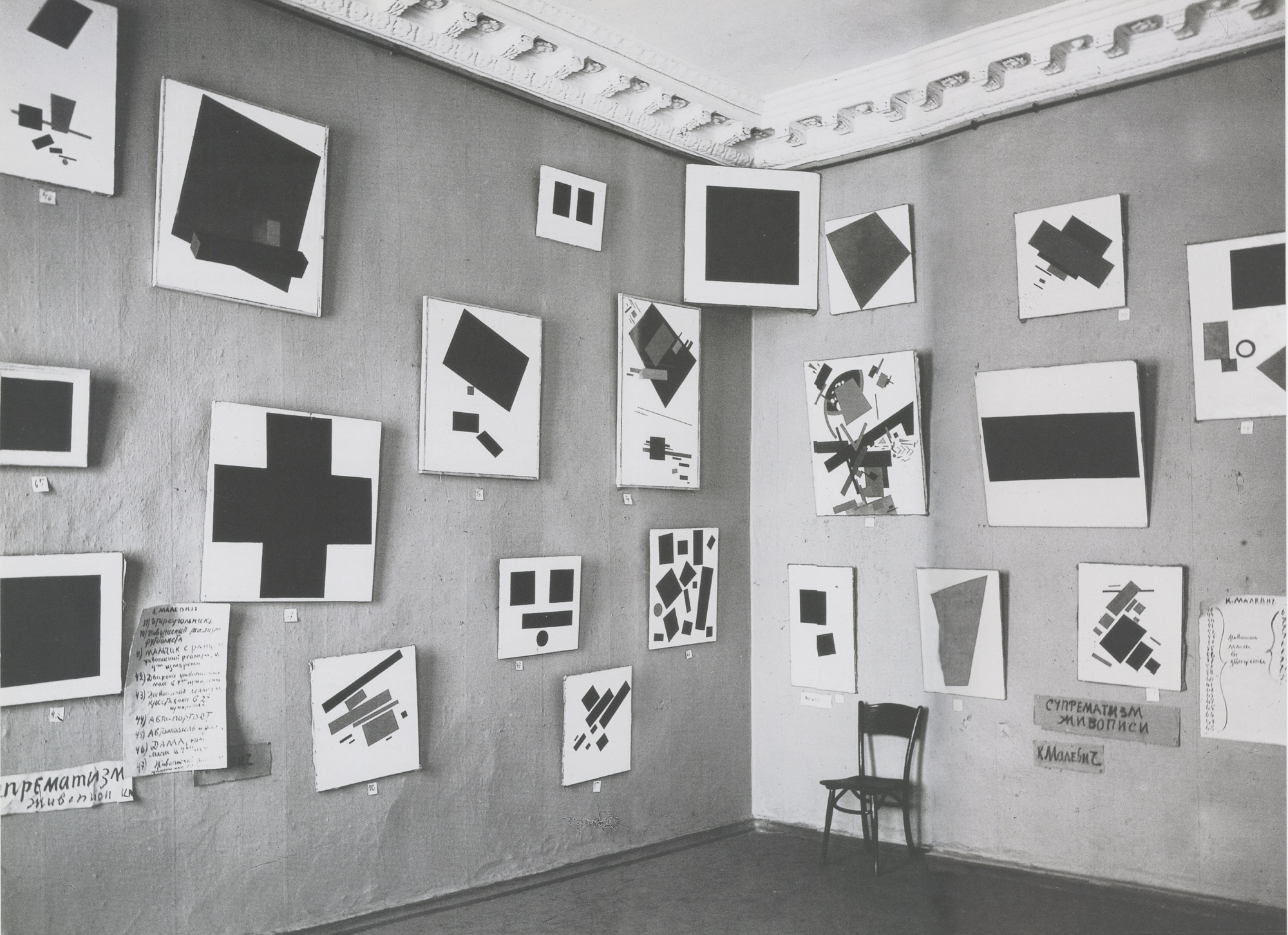

The exhibition presented 155 pieces by 14 artists, including 39 abstract paintings by Malevich. However, those numbers are only estimates as it is impossible to determine the exact number of works – even the catalog did not include everything displayed and several artists added and removed their pieces during the show.

Above you can see a photo from the Last Futuristic Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 (zero-ten).

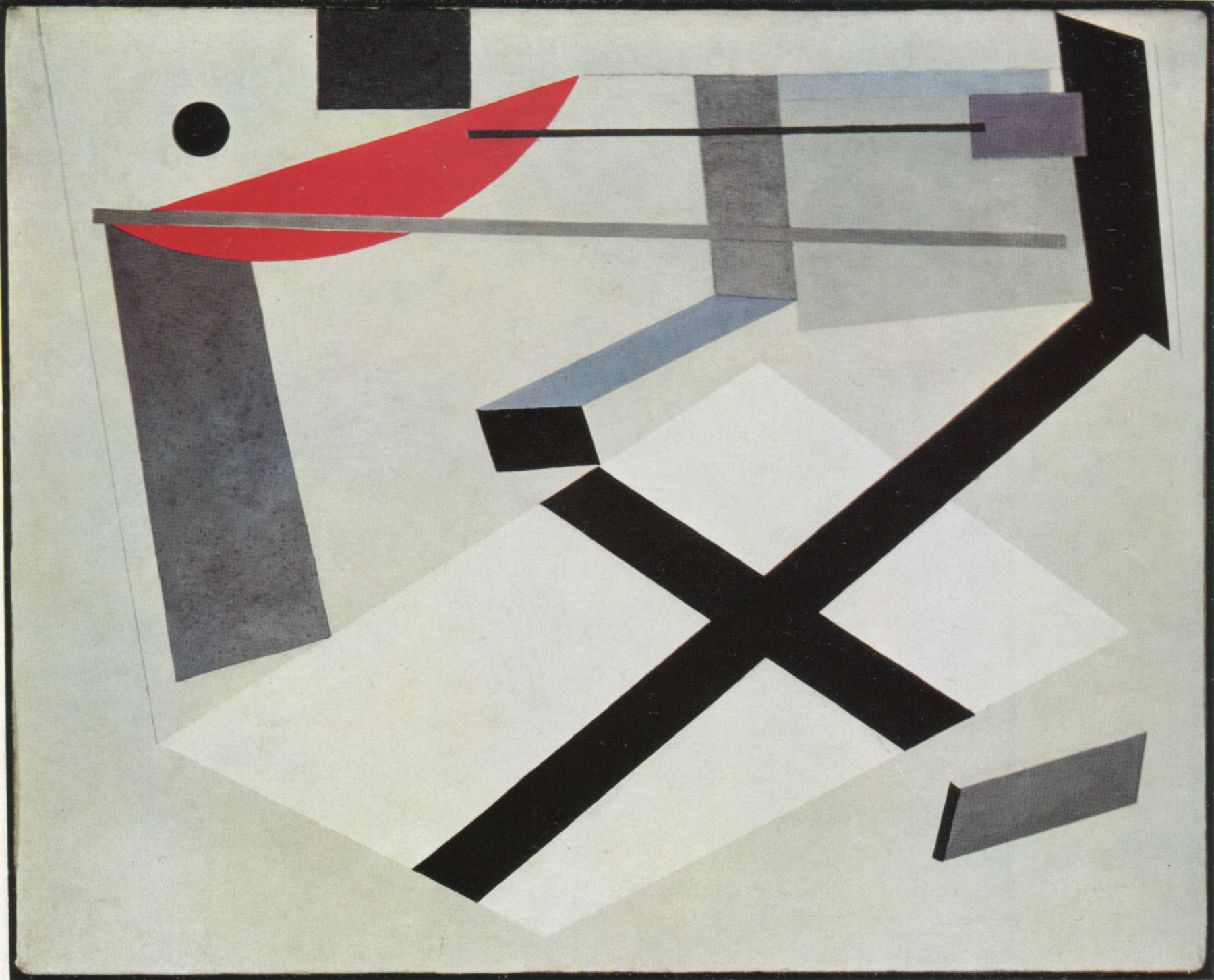

Apart from Malevich, the most prominent Suprematist artists were El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, and Olga Rozanova. Malevich divided the progression of Suprematism into three stages: “black,” “colored,” and “white.” The black phase marked the beginnings of the movement, and the “zero degree” of painting, as exemplified by the Black Square. The colored stage, sometimes referred to as Dynamic Suprematism, focused on the use of color and shape to create the sensation of movement in space. This was pursued in depth by Ilya Chashnik, El Lissitzky, and Alexander Rodchenko. El Lissitzky was particularly influenced by Malevich and developed his own personal style of Suprematism, which he called “Proun.”

This development of Suprematism came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. But as Stalinism took hold from 1924 on, the state began limiting the freedom of artists. From the late 1920s, the Russian avant-garde experienced direct and harsh criticism from the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of Socialist Realism became official policy and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression.

Malevich died of cancer at the age of 57, in Leningrad on 15 May 1935. His friends and disciples buried his ashes in a grave marked with a black square. On his deathbed, Malevich had been exhibited with the Black Square above him, and mourners at his funeral rally were permitted to wave a banner bearing a black square.

Apart from being an artist, Malevich is also remembered as an antimaterialistic philosopher:

I no longer consider Suprematism like a painter or like a form that I took out from a dark skull. I stand before it like an outsider contemplating a phenomenon.

Letter written by Malevich to Gershenzon on April 11, 1920, in: Kazimir Malevich, Собрание сочинений в пяти томах (Collected Works in Five Volumes), vol 3, Moscow; Gileia, 2000.

His works have been popularized by El Lissitzky, who left Russia. Today his works are held in several major art museums, including the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam owns 24 Malevich paintings, more than any other museum outside of Russia.

Linda Boersma, 0,10: The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting, Rotterdam: 0,10 Publications, 1994, pp. 50–51.

Kazimir Malevich, The manifesto released for the Last Futuristic Exhibition of Paintings: 0.10 (zero-ten), St. Petersburg, Russia: Matyushin, 1915.

Christina Lodder, “In Search of 0,10 – The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting”, in The Burlington Magazine, no. 158, 2016, pp. 61-63.

Kazimir Malevich, Собрание сочинений в пяти томах (Collected Works in Five Volumes), vol 3, Moscow: Gileia, 2000.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!