5 Contemporary Women Artists from Latin America You Need to Know

When we speak about contemporary art in Latin America, women artists are at the center stage. Working around various mediums and highlighting themes...

Natalia Tiberio 16 December 2024

Protest Art is challenging and controversial. Political protest requires a focus, and protest art gives us a public space where we can have a conversation, with the artist and with each other. So, let’s take a closer look at just one piece of explosive and controversial protest art. Come with me, we’re on a summer street in 1970s Brazil. Phew, hot, isn’t it? Anyone fancy a soft drink? Take a look at this glass Coca-Cola bottle. Examine the image closely, what do you see?

Truly great artists reflect back at us the culture, social conditions, and politics of our society. Art can witness our pain, it can outrage us, and it can provoke us. It can nudge us gently or it can push us over a cliff. Art can open up spaces for the marginalized and the excluded to be seen and heard.

German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno famously said, “all art is an uncommitted crime,” meaning that art challenges the status quo by its very nature.

These bottles were used as part of a project called Insertions into Ideological Circuits by the Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles. He was angry at the American funded military government which was ruling Brazil. Meireles purchased filled, sealed bottles of Coca-Cola, modified them by writing slogans on the outside of the bottle, then sent them back into circulation, to be bought and drunk by the public. After recycling they were refilled and sent back out again. Bottles read Go Home Yankees or even carried instructions on how to make a Molotov cocktail. A Molotov cocktail is a home-made petrol bomb. You take a bottle, you add particular amounts of fuel and detergent. You stuff in a rag, set fire to it then throw it. Boom!

I knew I was beginning to touch on something interesting. I was no longer working with metaphorical representations of situations; I was working with the real situation itself. Furthermore, the kind of work I was making had what could be described as a ‘volatilised’ form. It no longer referred to the cult of the isolated object; it existed in terms of what it could spark off in the body of society.

Extracts from artist’s notes on Insertions into Ideological Circuits (1970) and an interview with Antônio Manuel (1975) from Dan Cameron, Paulo Herkenhoff, Gerardo Mosquera, Cildo Meireles, Phaidon, London, 1999.

And why a Coca-Cola bottle? Well, this bottle is an everyday object of mass circulation. We all recognise it as a symbol of capitalist consumerism. And in 1970s Brazil it was a vivid symbol of US imperialism. The Daros Latin America Collection believes that this kind of work is the inverse of the ‘ready-made’ art of artists like Marcel Duchamp. Rather than placing a commercial object into the hallowed halls of the art gallery, Meireles inserts ‘noisy’ and disruptive art into the bland, homogenous world of commerce.

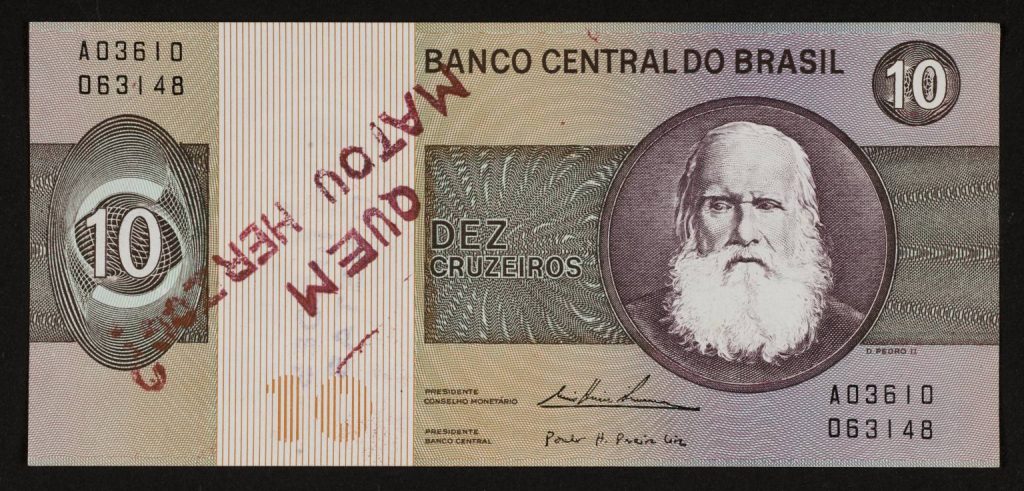

Meireles called this an act of ‘guerrilla warfare’ against capitalism and dictatorship. He did a similar artwork with messages written on banknotes. The Banknote Project harks back to the Suffragette Penny when women campaigning for emancipation hammered the words ‘Votes For Women’ on British pennies. We are talking about mobile graffiti that can be seen by hundreds of people. I think with this project Meireles wanted us to feel uncomfortable. And we do, don’t we? Molotov cocktail recipes on coke bottles – it raises all kinds of questions, doesn’t it? Is it ethical to share the recipe for a bomb? How far should you go when sending radical messages out to the general public?

The way I conceived it, the Insertions would only exist to the extent that they ceased to be the work of just one person. The work only exists to the extent that other people participate in it. What also arises is the need for anonymity. By extension, the question of anonymity involves the question of ownership. When the object of art becomes a practice, it becomes something over which you can have no control or ownership.

Cildo Meireles, in: Dan Cameron, Paulo Herkenhoff, Gerardo Mosquera, Cildo Meireles, Phaidon, London, 1999.

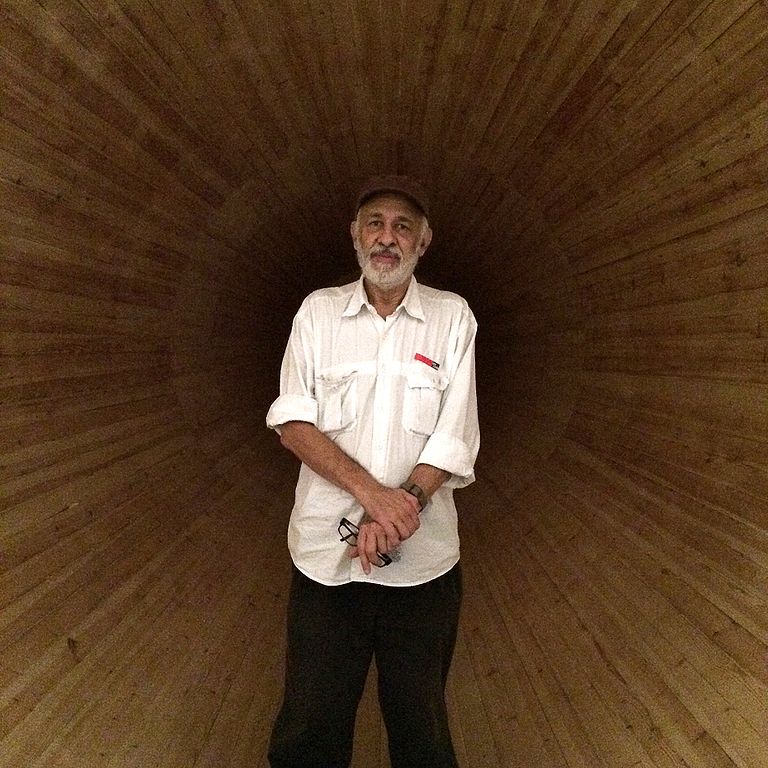

Meireles wants you, the public, to be a part of the artwork, to be the artwork. As you pick up the bottle you may not even be aware that it is art. But either way, the viewer becomes participant. As Spiderman says, ‘with great power comes great responsibility.’ Mereiles is so incensed by the US military machine destroying his country, that he feels he must make a big statement, a scary statement. That is to say, he is inciting his fellow country men and women to get out on the streets, to fight back. What do you think? Today we live in a world of rapidly evolving social communication systems. Meireles’ work is as valid and poignant today as back in the 1970s. He continues to work to this day, and was the first Brazilian artist to receive a full career retrospective by Tate in London in 2008.

I’ll leave you with two ideas to mull over today: Should artists involve the public in their radical politics? And is it ethical to break the law? I think I agree with Helena Kennedy, the British barrister, broadcaster and human rights lawyer. She said that sometimes it is all we can do. The question is, how far would you go?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!