The Miniature Rooms of Narcissa Niblack Thorne

The Thorne miniature rooms are the brainchild of Narcissa Thorne, who crafted them between 1932 and 1940 on a 1:12 scale. Incredibly detailed and...

Maya M. Tola 9 January 2025

During one of my vacations, I got an unexpected treat – the opportunity to see two amazing collections of Fabergé Easter eggs in two days. One collection was at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia, and the other was at Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens in Washington DC. Read some fascinating facts about the famous Fabergé Easter eggs.

In case you’re not familiar, the House Fabergé was a 19th and early-20th-century company that is most famous for creating lavish Imperial Easter eggs for the Russian Imperial family. You can see works by Fabergé in quite a few museums, but having this opportunity to look at two large collections in as many days allowed me to learn many new things about Fabergé and its eggs.

There are Easter eggs in the Easter eggs, so to speak. Most of the time, when we focus on the outside of the egg, which is usually made of enamel and gold and decorated with detailed patterns of precious stones. However, what’s inside the egg is almost always as spectacular as the shell. All of the Easter eggs open to reveal tiny surprises. Sometimes, it was one or more watercolors on ivory portraits, often of beloved family members. Other times, it might be a tiny statue of a historical Russian figure like Peter the Great or a mechanical marvel. Most Fabergé Easter eggs still have their surprises, which are usually displayed alongside the egg. Unfortunately, though, some surprises are now lost.

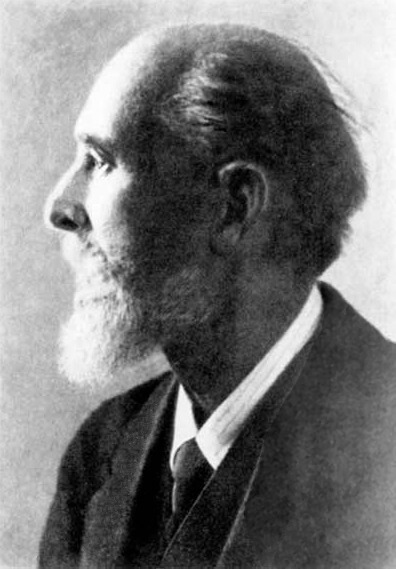

Tsar Alexander III (1845-1894) began the Imperial tradition of commissioning Fabergé Easter eggs in the 1880s. He gave the eggs as gifts to his wife, Maria Feodorovna. After Alexander’s death, his son, Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918), doubly carried on the tradition by giving eggs annually both to his widowed mother and to his wife, Alexandra. More eggs for us to enjoy today! Because his mother long outlived his father, he had to keep commissioning two eggs right up until he was forced to abdicate the Russian throne in 1917.

This makes sense since they were family gifts. One of the most personal eggs that I saw was the Red Cross Portraits Egg, which Nicholas II gave to his mother in 1915. Maria Feodorovna was the head of the Russian Red Cross, and she was very active in the organization’s work during World War I, so her son paid tribute to her efforts in a wartime egg.

Inside the egg, there was a series of portraits depicting women in the imperial family – Maria’s daughter, granddaughters, daughter-in-law, and niece – in Red Cross uniforms. Another very personal egg, the Tsarevich Egg, opened to reveal a small portrait of Nicholas and Alexandra’s son, Alexis, in a diamond and platinum frame (Tsarevich was the Russian term for the Crown Prince).

Not all Fabergé Easter eggs were specifically personal to the Romanov family. Others celebrated their country instead. For example, the Peter the Great Egg and the Catherine the Great Egg paid homage to two of Nicholas’s most illustrious imperial predecessors. Nicholas gave the former egg to his wife in 1903 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Peter’s founding of the eponymous Saint Petersburg. The egg has tiny painted scenes of Saint Petersburg on the sides, and it opens to reveal a tiny, gold and sapphire statue of Peter the Great.

I kept coming back to take another (and another, and another…) look at each egg on display, and I kept feeling like seeing them for the first time. That’s because the details are so tiny and perfect that you can’t possibly absorb them all on the first viewing. This was particularly true of the Catherine the Great Egg, which I saw at Hillwood.

That egg is very fancy, with seemingly-endless tiny gold decorations to lose yourself in, but this is also true of eggs with simpler designs. The Red Cross Portraits Egg looks at first like its shell is just a solid, silvery-white enamel. But look closely, and you’ll realize that there’s actually a texture and subtle patterning to the ground. This technique is called guilloche.

The Russian language is written in the Cyrillic alphabet, so it might not be immediately recognizable to people like me who are used to the Latin alphabet. It was helpful to have literature and audio guides to tell me that Cyrillic initials can be found on many of the Fabergé Easter eggs. For example, what looks like pure decoration on the sides of the Alexander III Portraits Egg is actually the initials of Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna. I enjoyed looking for the initials of Alexandra Feodorovna on some of the other eggs since my name is also Alexandra.

I saw loads of miniature Fabergé Easter eggs at the Virginia Museum and a few at Hillwood, too. They’re mainly little pendants, like for a necklace that are less than an inch high. They are of course much less detailed than the full-sized eggs, but they’re made of the same precious metals and stones. I like to think of them as the souvenir versions of the Imperial eggs.

I also saw lots of Fabergé picture frames, bell pushes, music boxes, silverware, cane handles, and even a few religious icons. For the most part, they’re not as fancy as the Imperial eggs, but they show the same techniques and masterful craftsmanship. I particularly loved a glorious, pink and bejeweled music box that I saw at Hillwood.

Okay. I didn’t learn this one from looking at the eggs. I actually discovered it while preparing this article. The original Fabergé company closed in 1918, during the Bolshevik Revolution when the workshop was taken over by the state. Peter Carl Fabergé fled the country and died not long after. I’m not clear on how the new Fabergé is related to the old one, since it isn’t run by Fabergé’s descendants, and it isn’t a continuation of the old company. But it is apparently authorized to use the name, and it does make mini Easter eggs as well as some lovely jewelry.

How to See the Eggs? The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia owns five Imperial eggs, as well as countless other works by Fabergé and other Russian artists. They were collected by Lillian Thomas Pratt and are on display in the European galleries. Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens in Washington DC owns two eggs and many other Fabergé works collected by the museum’s founder, Marjorie Merriweather Post.

You can read more about my experiences with Fabergé eggs here and here. You can learn more about all the Fabergé Easter eggs, not just the ones I got to see, on the Fabergé Research Site.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!