The Sistine Chapel is one of the most famous art places in the world – all because of being the place where a new pope is selected and because of the magnificent frescos by Michelangelo that decorate the interior. The chapel is placed in the Apostolic Palace, the official residence of the Pope, in Vatican City Originally known as the Cappella Magna, the chapel takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who restored it between 1477 and 1480. But it is not the whole story about it.

Here we have 15 facts about Sistine Chapel you need to know!

1. The chapel was designed after the Temple of Salomon

The chapel is a high rectangular building, for which absolute measurements are hard to ascertain, as available measurements are for the interior: 40.9 metres (134 ft) long by 13.4 metres (44 ft) wide, the dimensions of the Temple of Solomon, as given in the Old Testament.

2. Michelangelo isn’t the only one from the top Renaissance artists there

Sistine Chapel has many fathers. During the reign of Sixtus IV, a team of Renaissance painters that included Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Pinturicchio, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli, created a series of frescos depicting the Life of Moses and the Life of Christ, offset by papal portraits above and trompe l’oeil drapery below.

3. It all started in 1483

These paintings were completed in 1482, and on 15 August 1483 Sixtus IV celebrated the first mass in the Sistine Chapel for the Feast of the Assumption, at which ceremony the chapel was consecrated and dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

4. Michelangelo had no idea what to paint…

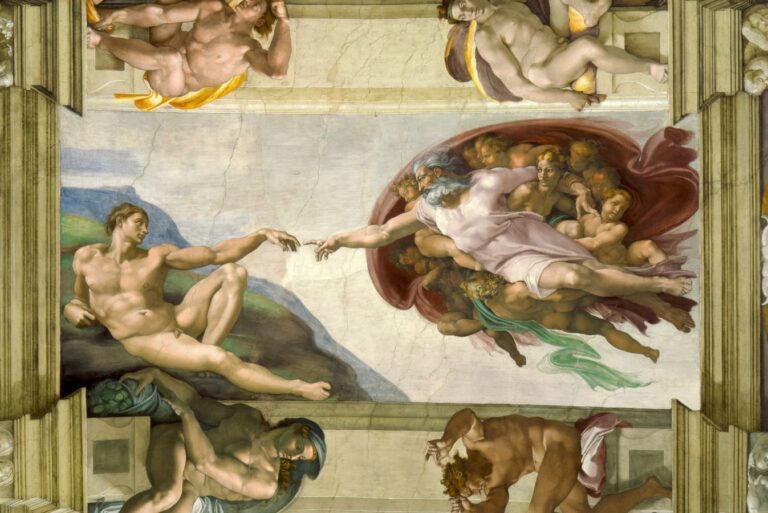

On Day 1 Michelangelo Buonarroti, a 33-year-old artist knew he was going to paint “Genesis” from the bible, but he started without sketching a single line on the ceiling. The commission was originally to paint the twelve apostles on the triangular pendentives which support the vault; however, Michelangelo demanded a free hand in the pictorial content of the scheme. He painted a series of nine pictures showing God’s Creation of the World, God’s Relationship with Mankind, and Mankind’s Fall from God’s Grace. On the large pendentives, he painted twelve Biblical and Classical men and women who prophesied that God would send Jesus Christ for the salvation of mankind, and around the upper parts of the windows, the Ancestors of Christ.

5. …and was scared by this commission

Michelangelo was shocked and intimidated by the scale of the commission, and it is known that he would have preferred to decline. He felt he was more of a sculptor than a painter. Possibly the commission was given to him on purpose because his rival Raphael was sure that Michelangelo would fail and that it would destroy his career. Michelangelo at this time was busy with the work on Pope Julius II’s marble tomb, a relatively obscure piece now located in Rome’s San Pietro in Vincoli church. He would return intermittently to Julius’ monumental tomb over the next few decades.

6. To do the thing, Michelangelo builds a scaffold of his own…

The ceiling of the chapel is pretty high – Michelangelo needed a support to get to it. Initially, he asked Julius’ favoured architect Donato Bramante to build for him a scaffold to be suspended in the air with ropes. However, Bramante did not successfully complete the task, and the structure he built was flawed. He had perforated the vault in order to lower strings to secure the scaffold. Michelangelo laughed when he saw the structure, and believed it would leave holes in the ceiling once the work was ended. He asked Bramante what was to happen when the painter reached the perforations, but the architect had no answer.

So Michelangelo built a scaffold on his own. He created a flat wooden platform on brackets built out from holes in the wall, high up near the top of the windows. Contrary to popular belief, he did not lie on this scaffolding while he painted, but painted from a standing position. He even wrote a poem about how rigorous it all was:

My beard turns up to heaven; my nape (back of a person’s neck) falls in,

Fixed on my spine: my breast-bone visibly

Grows like a harp: a rich embroidery

Bedews my face from brush-drops thick and thin.

By the way, Michelangelo wrote a log of poetry.

7. Michelangelo was complaining about this work all the time

In 1509, Michelangelo described the physical strain of the Sistine Chapel project to his friend Giovanni da Pistoia. “I’ve already grown a goiter from this torture,” he wrote in a poem. His “stomach’s squashed under my chin,” that his “face makes a fine floor for droppings,” that his “skin hangs loose below me” and that his “spine’s all knotted from folding myself over.” He ended with an affirmation that he shouldn’t have changed his day job: “I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.”

Good that however he occured to be one!

8. Michelangelo painted… a brain?

Well, it sounds crazy but there is a theory that there may be a hidden brain in The Creation of Adam. The shape created by the angels and robes surrounding God bears an uncanny resemblance to the human brain, complete with stem, frontal lobe and artery. Given Michelangelo’s anatomical studies, it’s unlikely to be coincidental.

9. The Last Judgement was created nearly 30 years after the ceiling and it caused massive controversy

The Last Judgement was painted by Michelangelo from 1535 to 1541, between two important historic events, the Sack of Rome by mercenary forces of the Holy Roman Empire in 1527 and the Council of Trent which commenced in 1545. The work was designed on a grand scale, and spans the entire wall behind the altar of the Sistine Chapel. The painting depicts the second coming of Christ on the Day of Judgment as described in the Revelation of John, Chapter 20.

The Last Judgement was an object of a bitter dispute between Cardinal Carafa and Michelangelo. Because he depicted A LOT OF naked figures, the artist was accused of immorality and obscenity. A censorship campaign (known as the “Fig-Leaf Campaign”) was organized by Carafa and Monsignor Sernini (Mantua’s ambassador) to remove the frescoes.

The Pope’s Master of Ceremonies Biagio da Cesena said:

“It was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.”

In response Michelangelo worked da Cesena’s semblance into the scene as Minos, judge of the underworld. It is said that when he complained to the Pope, the pontiff responded that his jurisdiction did not extend to hell, so the portrait would have to remain.

10. Daniele da Volterra was the guy who covered all nudity

Daniele da Volterra was the artist who had also a major part in the creation of the Last Judgement. After the fresco was completed, he was hired in 1560s by Pope Pius IV to cover the genitalia of the characters presented there. He was later known as “Il Braghettone” (“the breeches-painter”). He also chiseled away and entirely repainted the larger part of Saint Catherine and the entire figure of Saint Blaise behind her. This was done because in the original version Blaise had appeared to look at Catherine’s naked behind, and because to some observers the position of their bodies suggested sexual intercourse.

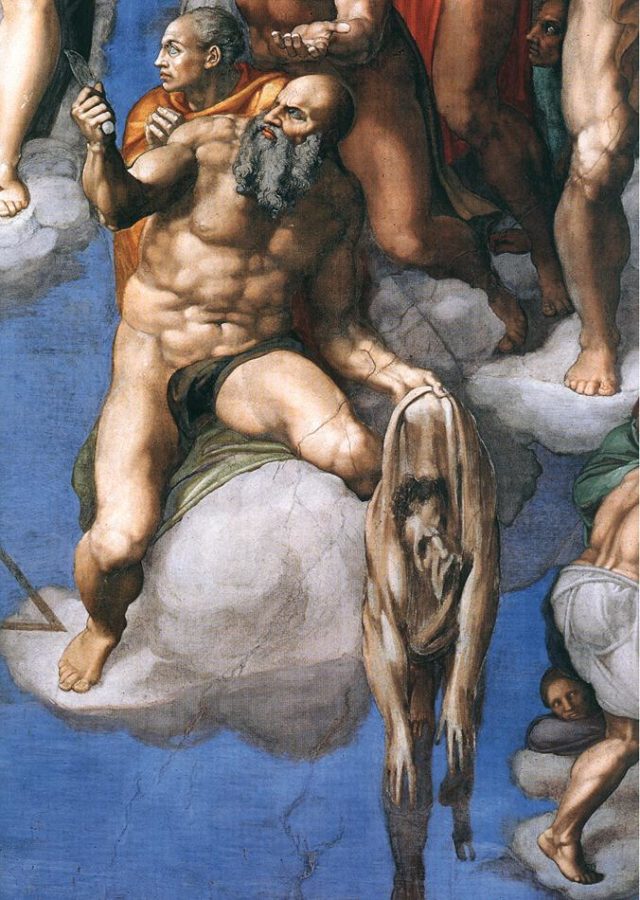

11. Michelangelo painted himself on the fresco

Michelangelo’s self-portrait takes the form of flayed skin. One of the many figures in the Last Judgement painting on the altar wall is St Bartholomew, who was flayed alive. The saint holds his own skin, which is commonly interpreted as the artist’s own melancholy portrait.

12. Raphael designed tapestries

In 1515, Raphael was commissioned by Pope Leo X to design a series of ten tapestries to hang around the lower tier of the walls. The tapestries depict events from the Life of St. Peter and the Life of St. Paul, the founders of the Christian Church in Rome, as described in the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. Work began in mid-1515. Due to their large size, manufacture of the hangings was carried out in Brussels, and took four years under the hands of the weavers in the shop of Pieter van Aelst. Raphael’s tapestries were looted during the Sack of Rome in 1527 and were either burnt for their precious metal content or were scattered around Europe. In the late 20th century, a set was reassembled from several further sets that had been made after the first set, and displayed again in the Sistine Chapel in 1983. The tapestries continue in use at occasional ceremonies of particular importance. The full-size preparatory cartoons for seven of the ten tapestries are known as the Raphael Cartoons and are in London.

13. For hundreds of years, the chapel was very dirty… all because of the cardinals

One of the functions of the Sistine Chapel is as a venue for the election of each successive pope in a conclave of the College of Cardinals. On the occasion of a conclave, a chimney is installed in the roof of the chapel, from which smoke arises as a signal. If white smoke appears, created by burning the ballots of the election, a new Pope has been elected. If a candidate receives less than a two-thirds vote, the Cardinals send up black smoke — created by burning the ballots along with wet straw and chemical additives — it means that no successful election has yet occurred.

The Cardinals during the election can’t leave the room. It means, that the conclave also provided for the Cardinals a space in which they can hear mass, and in which they can eat, sleep, and pass time attended by servants. The smoke and pollution made the frescos dark and dirty.

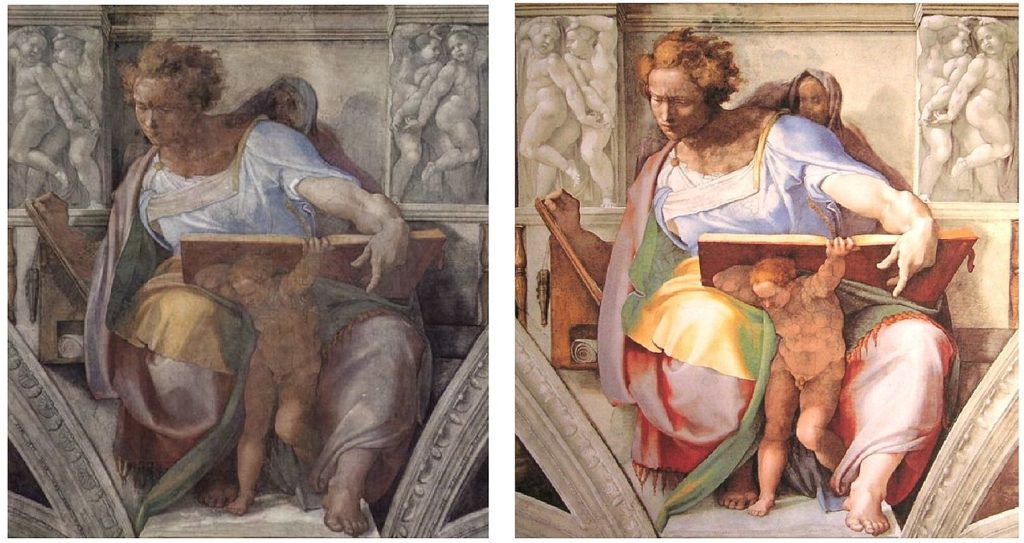

14. The chapel has been restored but there is a concern

The Sistine Chapel’s ceiling restoration began on 7th November 1984. It was finished 10 years later. But there is a concern that the processes being employed in the cleaning were too severe and removed the original intent of the artist. A close examination of the frescoes of the lunettes convinced the restorers that Michelangelo worked exclusively in “buon fresco”; that is, the artist worked only on freshly laid plaster and each section of work was completed while the plaster was still in its fresh state. In other words, Michelangelo did not work “a secco”; he did not come back later and add details to the dry plaster.

The restorers, assuming that the artist had taken a universal approach to painting, took a universal approach to the restoration. A decision was made that all of the shadowy layer of animal glue and “lamp black”, all of the wax, and all of the overpainted areas were contamination of one sort or another: smoke deposits, earlier restoration attempts, and painted definition by later restorers in an attempt to enliven the appearance of the work. Based on this decision, according to Arguimbau’s critical reading of the restoration data that was provided, the chemists of the restoration team decided upon a solvent that would effectively strip the ceiling down to its paint-impregnated plaster. After treatment, only that which was painted “buon fresco” would remain.

15. The ceiling has its full-sized replica

The reproduction of the Sistine Chapel ceiling was painted by Gary Bevans at a church in Goring-by-Sea, West Sussex, England, although he never had an art lesson. More recently, this full-size architectural and photographic replica of the entire building was commissioned by the Mexican Government and funded by private donors. Now it travels around the world. It took 2.6 million high definition photographs to reproduce the totality of the frescoes and tapestries.