Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals at Tate

Two of Britain’s most famous Romantic painters meet again in Tate Britain’s new exhibition. Turner & Constable: Rivals and Originals...

Sandra Juszczyk 8 December 2025

In 1878, artist James Whistler sued critic John Ruskin over a bad review. The trial and its consequences, set against the background of the Victorian art world, are the subject of Falling Rocket: James Whistler, John Ruskin and the Battle for Modern Art, a new book by historian Paul Thomas Murphy, published by Pegasus Books.

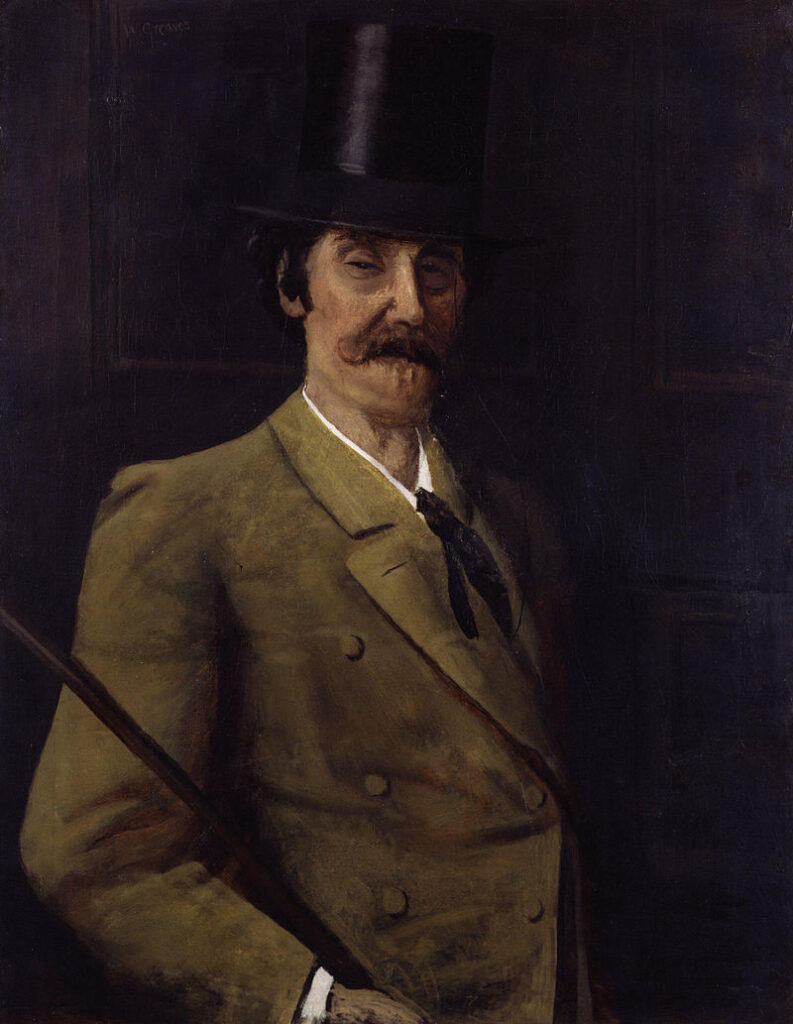

Walter Greaves, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, c. 1875, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Greaves is one of the many friends and supporters with whom Whistler falls out during the book.

Paul Thomas Murphy has an established career as an academic, teaching and researching, initially Victorian literature and then culture more broadly. His two previous books, like Falling Rocket, have taken notable events that readers may even be familiar with and used them as the starting point for a broader exploration of the world of the 19th century.

While Falling Rocket features less obviously dramatic subject matter, Murphy employs the same balance of primary resource research and dynamic storytelling. His work is full of detailed facts, but they sit lightly within a narrative style, which could just as easily be fiction. This is not a criticism: Murphy produces a thoroughly enjoyable read.

John Ruskin, Self Portrait, 1875.

At 400 pages, this is long enough to get stuck in but divided into ten easily digestible chapters, plus an epilogue. It is not an art history book, and the illustrations are small and limited to the central pages, but they are well reproduced, mostly in color. Arguably, it might help to integrate more of them within the text better. It is sometimes frustrating to read about paintings in which you cannot see yourself. However, that would be a different book.

What you do get is a very comprehensive index, bibliography, and notes. Falling Rocket has been thoroughly researched, deceptively so. You are not bogged down in footnotes and fact-checks, but it is evident that Murphy makes the most of his academic background and takes his history seriously.

The cover and title, if anything, undersell what is on offer. If you are unfamiliar with the two protagonists or the painting Falling Rocket, I am not sure you would be tempted to pick the book up. The subtitle, The Battle for Modern Art, conjures an image of dry academic debate and might put people off. Yet there is much to offer the general reader, and Murphy’s writing style is highly accessible.

James McNeill Whistler, The Peacock Room, 1876-1877, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA. Photograph by Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0). The exorbitant and disputed cost of the room, designed for Frederick Leyland, features in Chapter Four.

Falling Rocket starts with a chapter devoted to each of the two protagonists, John Ruskin and James McNeill Whistler, followed by a third split between them. In each case, Murphy provides a whistlestop summary of their lives and careers up to the main period of action, the mid-1870s, cleverly hanging both biographies around the considerable characters of the men’s mothers.

James McNeill Whistler is presented as an unreliable, fractious, but rather loveable rogue: he makes and breaks friendships with ease, drifts carelessly in and out of relationships, struggles with his painting, and sometimes resorts to physical violence. John Ruskin is a more complicated character to draw empathetically. Cosetted by his parents, disturbed by physical intimacy, and prone to bouts of mental instability, he is deeply spiritual, intense, intellectual, and serious. He is also, crucially, fifteen years older.

Murphy is a marvelously impressionistic writer, conjuring up pen portraits of these two men from brief anecdotes and isolated details. The pace is breathless; the events, names, and places come thick and fast, but by the start of chapter four, you feel you know both Whistler and Ruskin, and both are rounded, complex characters.

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, c. 1875, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI, USA.

The central chapters give a chronological narration of the events leading up to the 1878 trial in which Whistler sued Ruskin for libel over comments about Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket. We get a brief history of the Grosvenor Gallery, with a detailed description of the 1877 exhibition, including contemporary critics’ remarks, Ruskin’s celebrated comments, and why they particularly offended Whistler.

Whistler’s precarious finances, mainly caused by his extravagance and stubbornness over the creation of the Peacock Room and his vanity project home, The White House, were significant factors in his decision to sue. Murphy catalogs them and gives an account of the protracted pretrial negotiations: legal teams, decisions about witnesses, what paintings should be exhibited and where.

His description of the trial itself is a tour-de-force. Pompous lawyers, a packed courtroom, paintings being handed around as evidence, and Whistler’s Wildean witticisms as he relishes being the center of attention. The confusion of the proceedings is all too apparent, even before the bizarre conclusion, which sees Whistler claim a hollow victory and damages of a mere farthing.

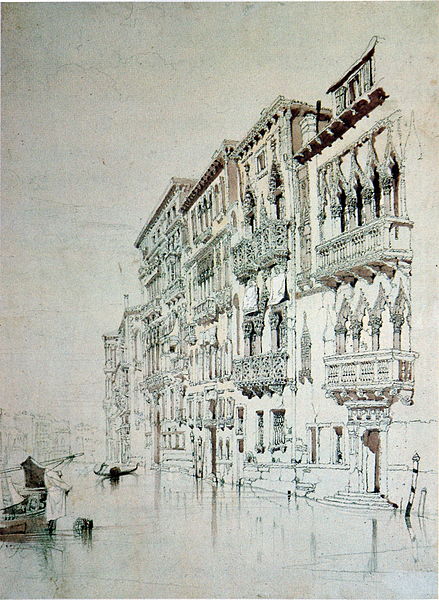

John Ruskin, Casa Contarini Fasan, Venice, 1841, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK. Ruskin was obsessed with Venetian architecture, fuelled by visits there and his love for JMW Turner‘s work.

The last chapters are perhaps less successful. Following the same alternating pattern as the start of the book, Murphy takes us through the impact of the verdict and the later life of both men in turn. The sections on Ruskin are shorter: he is an increasingly reclusive figure, dogged by physical and mental decline, ever more out of sympathy with a world that is moving forward without him.

Whistler, in contrast, is just getting started. More financial woes and money-making schemes, exhibitions in Europe and America, failed plans to infiltrate the establishment as President of the Society of British Artists. At the same time, there is what Whistler himself called ‘The Gentle Art of Making Enemies’: dubious affairs, failed friendships, endless self-promotion, and public spats with, among others, Oscar Wilde. Murphy is hindered by his main protagonist, an increasingly dislikeable character.

Arguably, there is just too much information in these last chapters, including an awful lot of art that is frustratingly difficult to keep track of. Sometimes, you want less detail and more analysis. The most successful section is the chapter on Venice, where Whistler retreated in 1879 and was a lifelong obsession for Ruskin. The two men saw the place so entirely differently that it is a microcosm of the gulf that separated them and their views on art.

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Gold, St Mark’s, Venice, 1880, Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales, Cardiff, UK.

The book’s subtitle only comes into play in the Epilogue, in which Murphy traces criticism of Whistler into the 20th century and positions him as a proto-abstract forerunner of Modernism. In the interest of balance, he also discusses, less convincingly, Ruskin’s long-term influence on the preservation of buildings and nature conservation.

There is so much more that could be said here. Murphy perhaps dodges the issue of discussing aesthetics and focuses instead on the legacy of the two men. However, he neatly ends as he begins, referencing Whistler’s portrait of his mother, which the artist saw as an ‘arrangement of grey and black,’ which the public still sees as a sentimental portrait.

Aubrey Beardsley, Caricature of J.M. Whistler, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA.

Perhaps Paul Thomas Murphy tries to do too much in Falling Rocket. There is so much information, names, and paintings that it can feel overwhelming. It isn’t easy to write a book about art that does not show the art and makes relatively little attempt to explain or describe it. There are moments when Murphy pauses to catch his breath – a discussion about moonlight and darkness, for instance – and then you realize how insightful he is.

That said, the book is written evocatively enough so that you want to know more, whether that is looking up pictures or investigating names. Murphy is entirely at home in Victorian Britain, as his command of the material shows. It is also cleverly written, with critical arguments woven throughout: ideas about the purpose of art and the role of critics, which, as he suggests in the Epilogue, still resonate today.

Falling Rocket is a good read for anyone interested in Whistler, Ruskin, or Victorian art. If it is all new to you, this is a thorough introduction. Someone looking for art history might be disappointed. But this is a good story, and it is told with dynamism, scholarship, and style.

You can get a copy of Falling Rocket on the publisher’s website.

Book Cover Falling Rocket: James Whistler, John Ruskin and the Battle for Modern Art Paul Thomas Murphy (Pegasus Books, 5th December 2023)

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!