Things You Didn’t Know About Henri Matisse’s Cut-Outs

Henri Matisse is known for his versatility in using different mediums and styles throughout his career as an artist. At the age of 60, he realized...

Seoyoung (Alyssa) Kim 26 August 2024

Can you believe that the now well-known masterpieces created by artists such as Henri Matisse and Maurice de Vlaminck were once called “wild art” in a derogatory way? And while we now admire all the Fauvist works, Fauvism used to be highly controversial. In this article, you will get to know why it was so shocking at the beginning of the 20th century through 10 paintings.

The first avant-garde movement of the 20th century was Fauvism. Much like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Fauvism earned its moniker from an art critic. During the Autumn Salon in 1905, painters including Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, Kees van Dongen, Albert Marquet, and others showcased their works. The art of these individuals was characterized by vibrant, intense colors, simplified forms, and a departure from the conventions of traditional classical art. This departure shocked the critic Louis Vauxcelles, who dubbed the painters “les fauves,” meaning “the wild beasts.”

It is acknowledged that Impressionism and Post-Impressionism also rebelled against the traditions and methods of academic art. While Post-Impressionists employed vivid colors, the Fauvists took it a step further. The art of Les Fauves was bound by the idea of the emotional potency of expression, the brilliance of open color, and the sharpness of rhythm. Thus, this sense of wildness played a pivotal role in shaping avant-garde art.

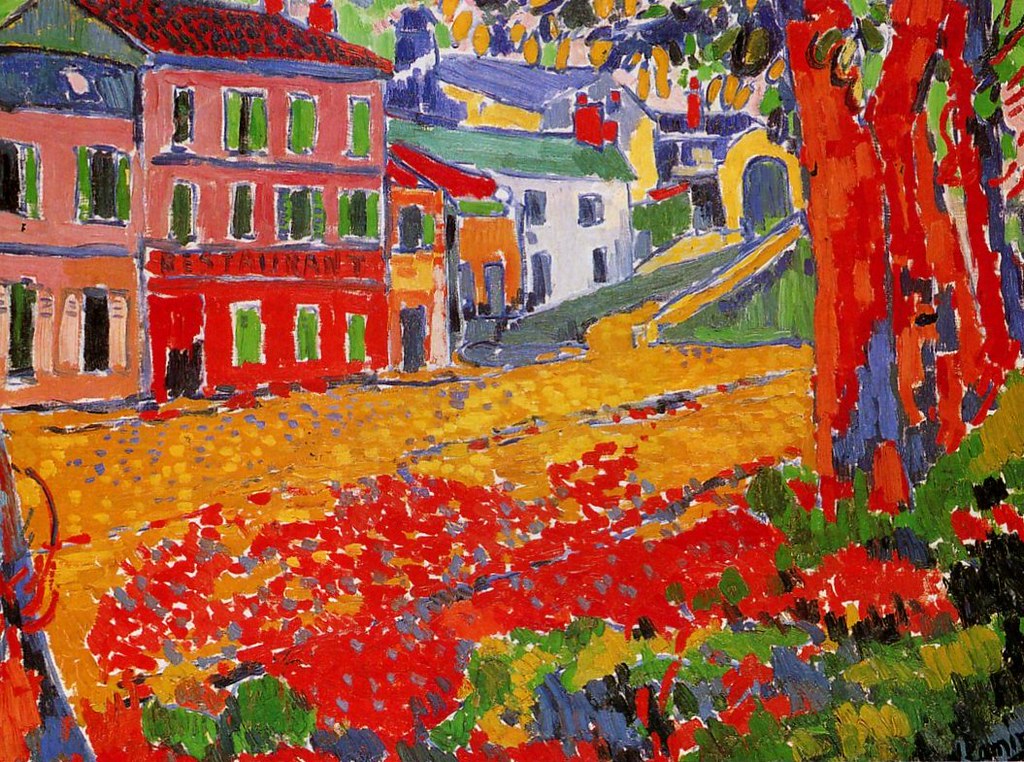

Maurice de Vlaminck, Restaurant de la Machine à Bougival, 1905, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Restaurant de la Machine à Bougival, created by Maurice de Vlaminck, was made in bright, vivid color. Shining red, orange, yellow, pink, and green fill the whole canvas. Vlaminck’s artistic style was profoundly influenced by the masterpieces of Van Gogh he encountered at an exhibition in 1901. From that point onward, Vlaminck adopted energetic brushstrokes and employed emotional colors in his paintings.

Fauvism drew inspiration from Post-Impressionism, particularly the art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Fauvist artists admired the vibrant use of color in the works of these masters and embraced the notion that color could take center stage in art. Color became the primary means of expressing emotions and impressions for them. They employed planes of pure colors, simplified forms by eliminating the third dimension, and juxtaposed contrasting colors.

Additionally, notable Fauvists such as Henri Matisse, Albert Marquet, and Georges Rouault were influenced by Gustave Moreau, a French painter associated with the Symbolist movement. Moreau instilled in his students an appreciation for pure color and emphasized that a crucial quality of a great artist lies in expressing oneself through paintings.

André Derain, Big Ben, 1907, Centre national d’art et de culture Georges-Pompidou, Paris, France.

Fauvists were inspired not only by the bold color used by representatives of Post-Impressionism but also by their technique. For example, André Derain painted Big Ben in a manner resembling Van Gogh’s oeuvre, namely Starry Night. However, later with the development of Fauvism, some painters went away from disjointed brushstrokes to plain colors.

As a rule, avant-garde art movements encompassed not only new forms of pictorial language but also new ideas often formed as manifestos. Despite thist, Fauvism was free from social or political agenda and pursued showing the beauty and joy of life through color.

Albert Marquet, Affiches à Trouville, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA.

Albert Marquet’s landscapes were filled with poetic simplicity. Even when Marquet painted with pure colors and resorted to contrasting colors, the combinations looked spectacular. So, the painting Affiches à Trouville is no exception.

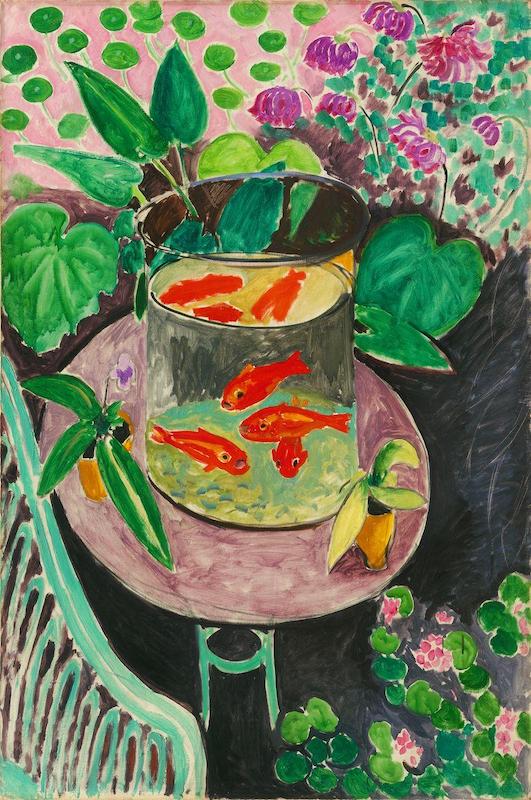

Henri Matisse, Goldfish, 1912, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia.

Henri Matisse’s Goldfish doesn’t carry any social, political, or mythological significance. In this instance, the fish is not a symbol of Christ; instead, it’s simply a representation of a fish. Matisse drew inspiration from his trip to Morocco and his fascination with the Moroccan way of life.

Fauvism departed from mimesis, the traditional principle of art that emphasized the imitation of reality. Classical painting had reached a point of exhaustion, where the mere replication of objects was no longer the primary goal. The dawn of the 20th century posed a different question to artists, and Fauvism emerged as one of the possible answers. Fauvists didn’t aim to depict the objective reality; instead, they sought to express how they felt about it through vibrant colors. In their paintings, the artists portrayed the world as they envisioned it, blurring the lines between reality and their imaginative interpretations.

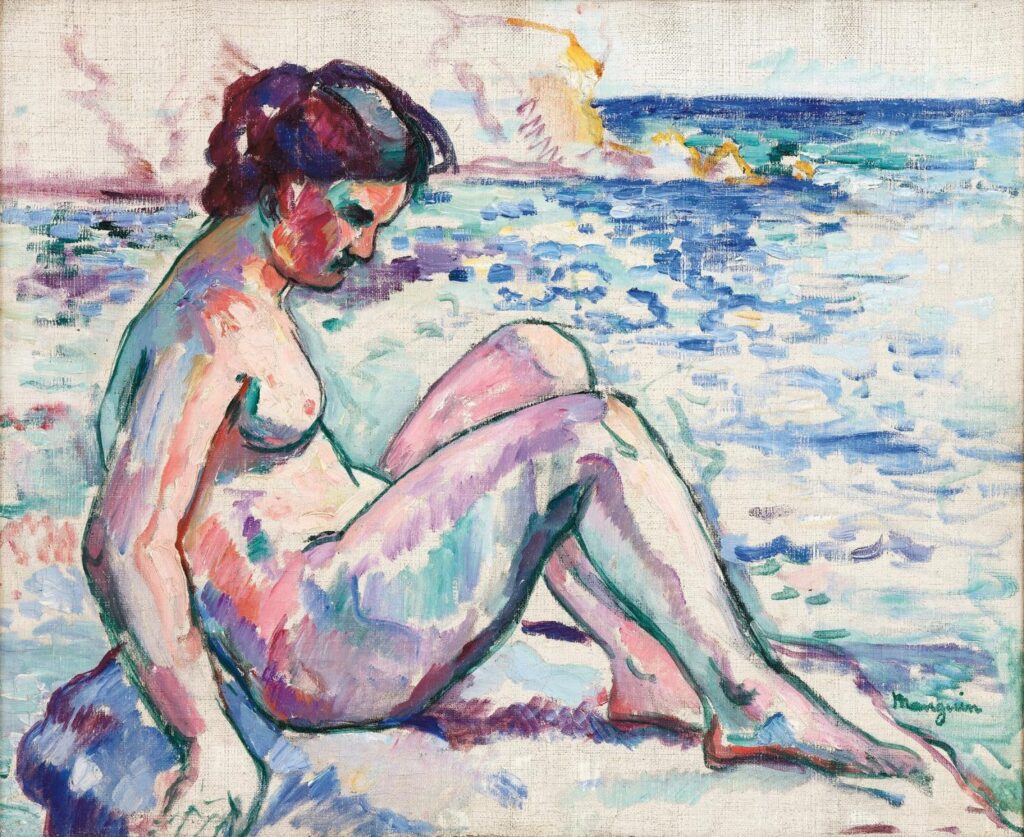

In this artwork, Henri Manguin skillfully applied the lessons from the Impressionist movement, portraying the shadows of the depicted woman in a nuanced array of colors. The harmonious combination of pink, lilac, and blue creates an impression of tenderness and subtle beauty.

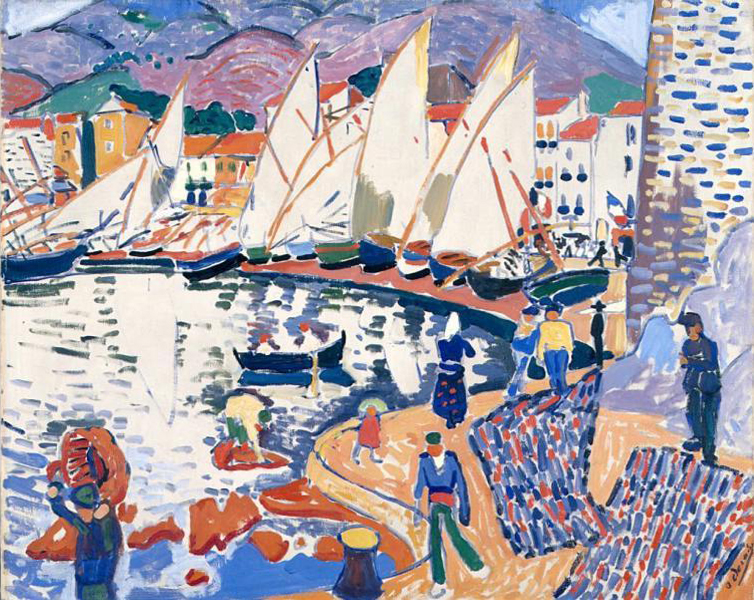

André Derain, The Drying Sails, 1905, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia.

The concept of expressing emotions and its influence, conceived among Fauvists, evolved in the theory of Wassily Kandinsky. He believed that various colors in distinct shapes triggered diverse emotional reactions within us. While Fauvists reveled in the potency of color and its vibrant, joyous energy, their predecessors like Van Gogh employed colors to convey dramatic states of the soul and intense emotions.

Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.

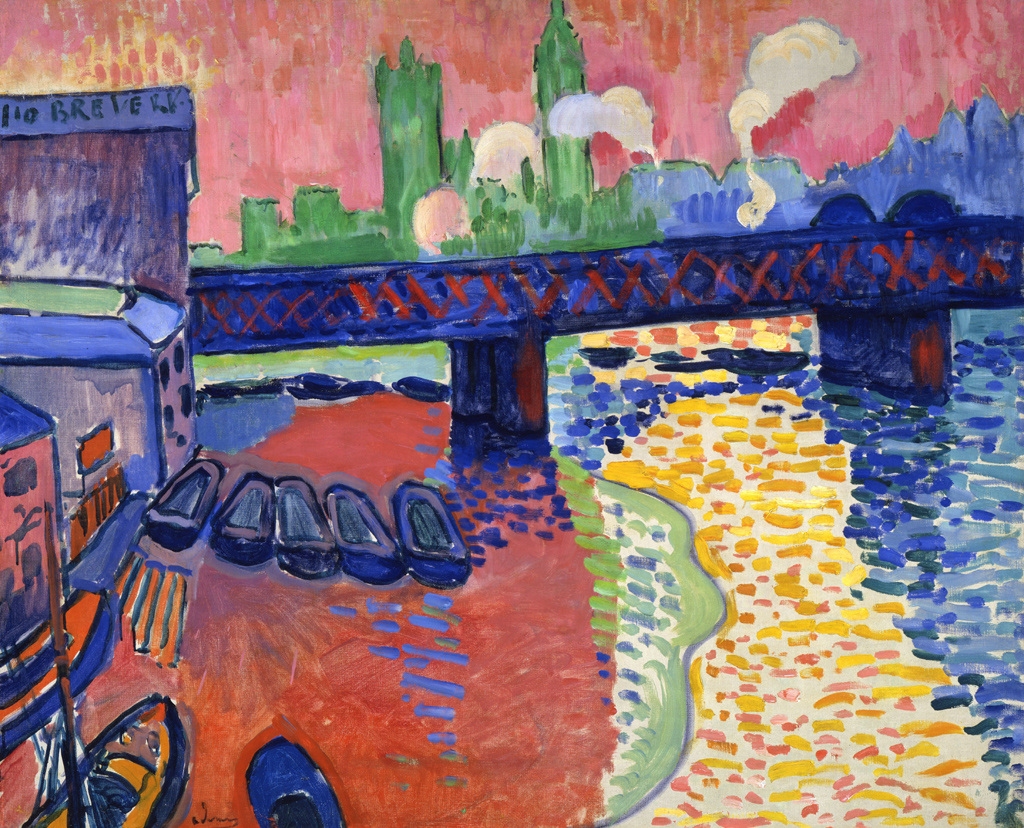

André Derain, Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA.

In Charing Cross Bridge, London, André Derain merged flat colors with disconnected brushstrokes. The nearly surreal colors suggest that the landscape served as a mere pretext to explore contrasting complementary colors.

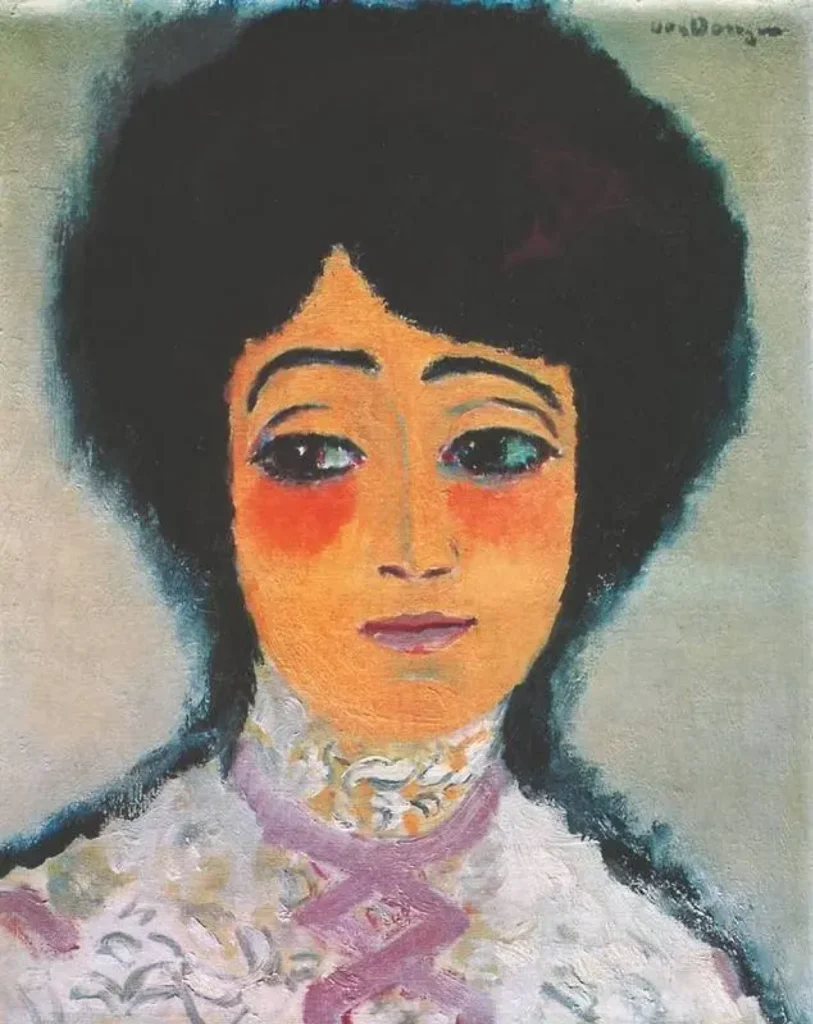

Kees van Dongen, Spanish woman, 1911, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia.

On Van Dongen’s canvases, vivid relief brushstrokes are combined with shining smooth zones, as if illuminated from within by electricity. The subjects of his paintings were provocative, often portraying characters from the societal “lower” positions.

The portrayal of landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and interiors served as a pretext for merging flat colors and reveling in their harmony. The lack of a third dimension created the impression that everything was part of a larger ornament. The spectators’ eyes wandered across the canvas, absorbing the vibrant colors. The Fauvists’ emancipation of color turned a detailed analysis of paintings into an ornamental meditation for the audience.

Henri Matisse, The Studio (The Pink Studio), 1911, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia.

Henri Matisse’s The Pink Studio delights the eye with its shades of pink and lilac, enhanced by ornate elements. Despite the depicted vase being empty, the ornamental flowers fill the space. This decorative quality, combined with the vibrant colors, establishes a unique idyllic atmosphere in the painting.

Fauvism established its rhythm through the expressive use of color. Despite the naive portrayal of objects, a sense of balance permeates the paintings. Take The Dance for instance, crafted with only three colors: red, green, and blue. The alternation of these colors creates the impression of a dance in both color and rhythm. Henri Matisse’s adept use of complementary contrasts contributes to the vibrant and expressive nature of the composition.

Henri Matisse, The Dance, 1910, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The Fauvist art movement had a relatively short lifespan, spanning from 1905 to 1908. Nevertheless, during this brief period Fauvist artists crafted masterpieces that defined their unique pictorial style. Henri Matisse, much like Claude Monet‘s enduring commitment to Impressionism, remained dedicated to Fauvism throughout his career.

Today, this pioneering avant-garde movement continues to captivate audiences, inspiring a desire to immerse ourselves in the vibrant world created by the Fauvists.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!