After receiving religious visions, James Hampton spent 14 years of his life preparing for Christ’s return to earth. When he died from stomach cancer in 1964, no one had any idea what he was creating in a rented carriage house. The work is called The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly and it is considered the greatest visionary art in the United States.

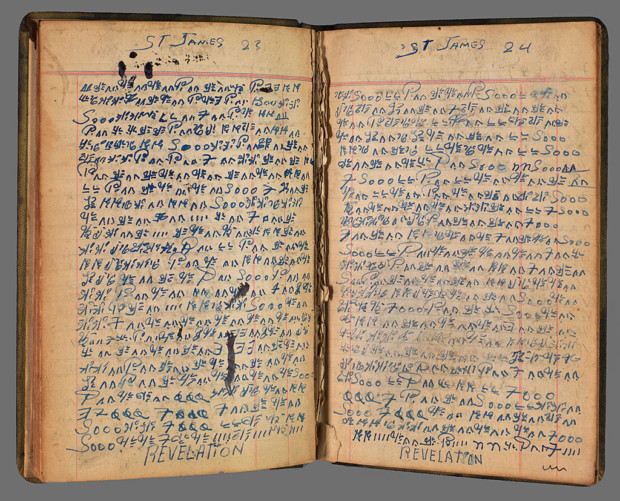

James Hampton was born in 1909 in Elloree, South Carolina. Hampton moved to Washington, D.C. when he was nineteen and started receiving visions of Moses and later, the Virgin Mary. Hampton wrote about his visions in notebooks in an unreadable spiritual script that no one has been able to decipher. Some parts are in English and in one part, he named himself, “Director, special projects for the state of eternity” and referred to himself as Saint James.

As the Director, James began to scavenge and salvage items from his work and around the neighborhood. He was a night janitor at a federal building and collected many pieces of cardboard, burnt out light bulbs, jelly jars, and colored foil from bottles and cigarette packs. He bought furniture from a second hand store. With these found items he created 180 elements of art in a highly decorative and symmetrical way. After his night shift, he worked alone and in secret on his project. At the center is a large cushioned throne with the words FEAR NOT written on a panel above. There are crowns, seats, altars, pulpits, and plaques that can be changed out according to the day. . . all covered in glittery foil and purple construction paper, which has unfortunately faded to a tan color.

The right side of the work represents the New Testament and Jesus, while the left side represents the Old Testament and Moses. On certain pieces, Hampton wrote notes that heavily relied on scripture and gave context to his work. The size and magnitude of the work is impressive. Unfortunately, pictures do not do it justice.

Hampton planned on opening a storefront ministry in the carriage house after he was finished creating his work, but did not live to carry out his plan. When the landlord did not receive his rent money after Hampton’s death, he unlocked the carriage house and was dazzled by a huge collection of glittery, ornate religious works of art. Luckily, he preserved the collection and it was donated to the Smithsonian, where you can visit it today.