5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

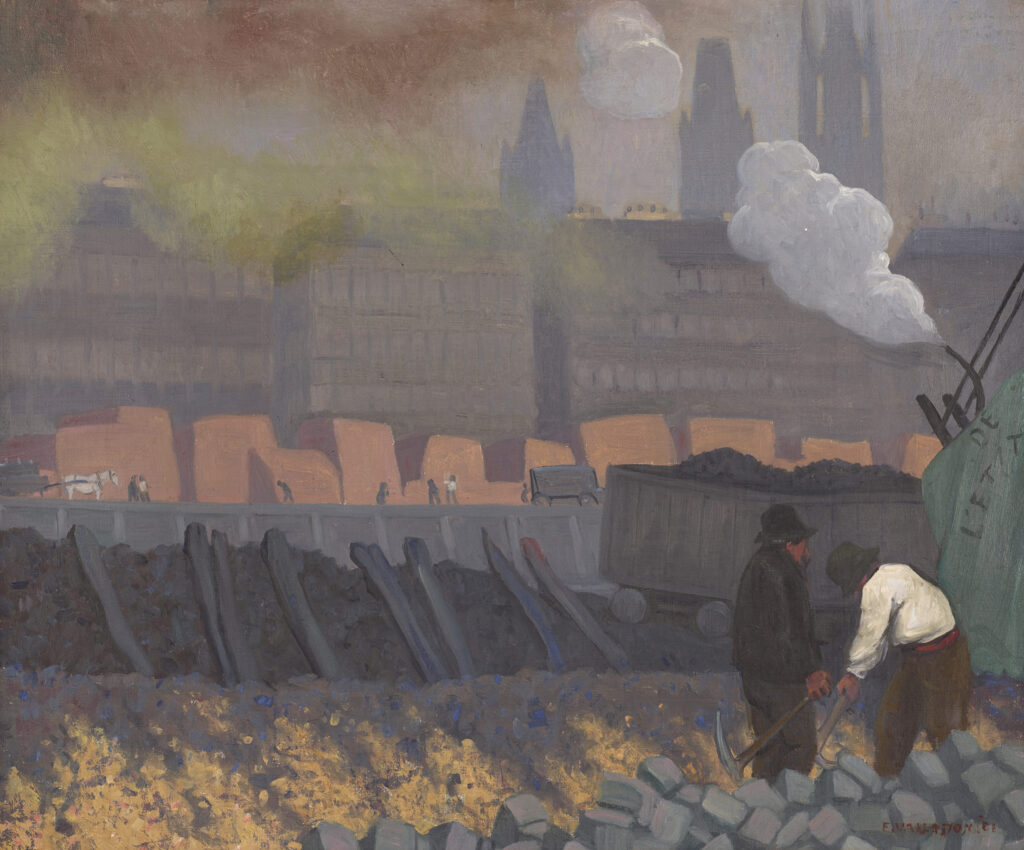

Félix Vallotton was a Swiss painter who left his home country to join the artistic nebula of Paris at the fin de siècle—the end of the century. He is mainly known for his wood engravings and illustrations of contemporary life in the French capital which was marked by the Industrial Revolution, a strong demographic rise and, consequently, an increase in class inequalities.

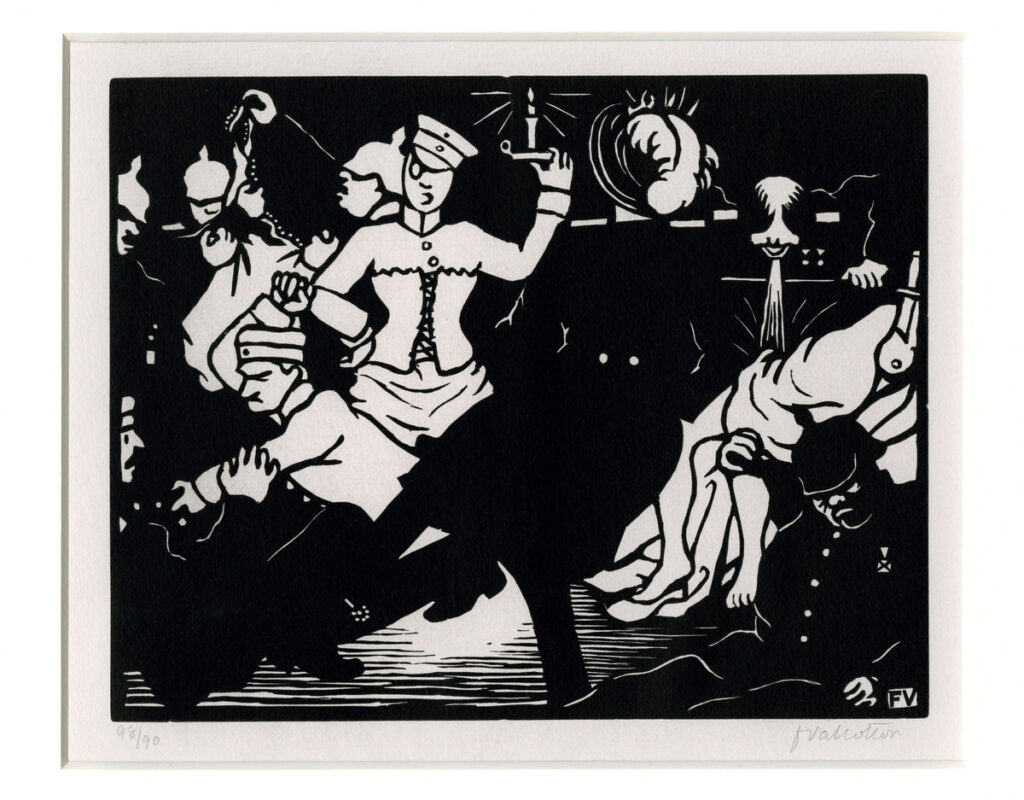

Félix Vallotton, The Orgy, from woodcut series C’est la Guerre!, 1915, Museum of Art and History, Geneva, Switzerland.

Félix Vallotton was born in 1865 in Lausanne, the capital of French-speaking Switzerland. At the age of 17, driven by his strong interest in painting, he moved to Paris and joined the Julian Academy. There, he met Charles Maurin, a libertarian painter, who introduced him to the artistic bohemian life of Montmartre. He quickly established himself among avant-garde artists who, inspired by Japanese prints, developed a pictorial language akin to Symbolism.

In 1890, he began a career in journalism as an art critic, and became involved in anarchist circles. In the following year, he produced numerous lithographs and woodcuts for satirical magazines such as L’Assiette au Beurre, Le Rire, L’Estampe Originale, and Les Temps Nouveaux, criticizing the abuses of social institutions through caricature.

Félix Vallotton, The Execution, 1894, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

In 1892, Vallotton became a member of the post-impressionist artist group called the Nabis. This collective, formed by Paul Sérusier, included painters such as Pierre Bonnard, René Piot, Maurice Denis, and Édouard Vuillard, all former students of the Julian Academy. They considered the practice of art to be a mystical quest aiming to represent the truth underlying appearances. In other words, they sought to bring to light a correlation between form and emotion through a synthetic pictorial treatment and a symbolic visual language.

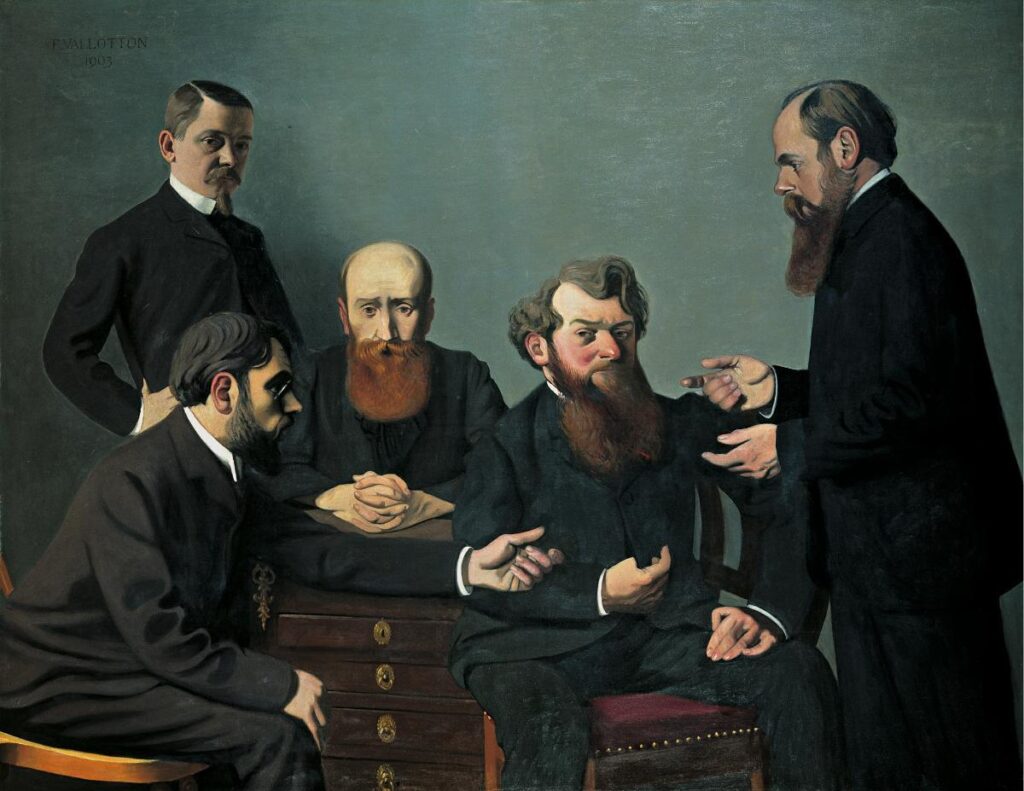

Félix Vallotton, The Five Painters, 1902-1903, Kunst Museum Winterthur, Winterhur, Switzerland.

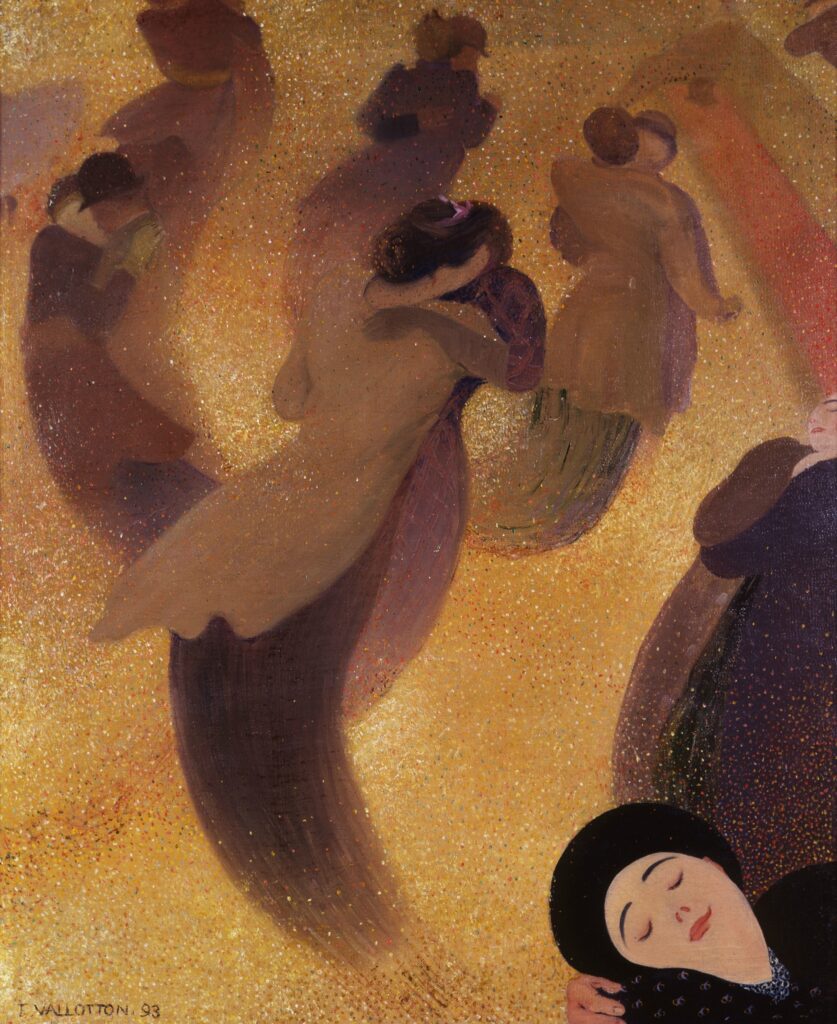

There, Félix Vallotton is known as the “foreign nabi,” not only because of his Swiss origin, but also because of the singularity of his style. Indeed, although his artwork is marked by a simplification of form, he contrasts with his contemporaries by using graded, non-uniform flat tints of color, creating an effect that is both airy and powerful through the use of complementary colors.

Félix Vallotton, The Waltz, 1893, Museum of Modern Art André Malraux, Le Havre, France.

The fin de siècle period in Paris was characterized by a renaissance of engravings. However, with the development of photography in the first half of the 19th century, this practice—whose main function had been to copy artworks—should have disappeared. Yet, the discovery of Japanese prints gave a new lease on life to engraving, especially woodcutting, and to the consideration given to composition in images. Furthermore, wood engraving was financially attractive to artists, as it was possible to make hundreds of prints from a single plate and sell them in large quantities at low prices.

Between 1891 and 1902, Félix Vallotton produced over 100 prints. The simple, straightforward rendering of woodcuts matched his increasingly caricatured and committed style. Many were published in or made exclusively for satirical magazines. His favorite themes were the crowd, the bourgeoisie, the state, and the clerical and military institutions, which he approached critically and humorously.

Félix Vallotton, First, Salute, it’s the Prefecture’s Car, from the series Crime et Châtiment published in L’Assiette au Beurre, 1902, a lithograph in three colors on wove paper, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Vallotton left the Nabis and abandoned printmaking for painting. This was probably linked to his marriage to a merchant’s daughter in 1899, which ensured him a certain financial ease. During the first quarter of the century, he painted more sober themes–such as landscapes, nudes, and still lifes–while maintaining a characteristic style developed for over almost 20 years in avant-garde circles. Contrasting to his prints, he mostly represented interior and intimate scenes. Nevertheless, in 1915, at the height of the First World War, he published a series of six woodcuts entitled C’est la Guerre! (That’s war!). Although he was unable to enlist because of his Swiss origins, he played his part in denouncing the horrors of war and its absurdity in his visual art.

Félix Vallotton, Rouen’s Port, 1901, Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Afterward, he traveled throughout Europe, exhibiting his work mainly in France and Switzerland, until he died in 1925 at the age of 60, following an operation for cancer. He left behind several thousand paintings, drawings, and engravings, some of which can be seen at the Félix Vallotton Foundation at the Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Félix Vallotton, Young Woman Sitting in Profile, 1914, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!